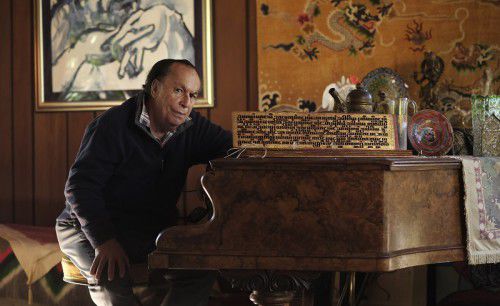

LARRY Sitsky and Tor Frømyhr filled the Sitsky Recital Room last Tuesday for “definitely Larry’s last 80th birthday concert”.

Beginning with Sitsky’s “Opus One” Sonata for solo violin, the program moved through Sitsky’s enigmatic “E” for solo piano, which obsesses around a single pitch, and concluded with Ferruccio Busoni’s gargantuan Sonata No. 2 for violin and piano (also nicknamed “Opus One”).

This virtuosic and demanding program exemplified what it means to belong to an artistic tradition. While Frømyhr channelled the Czech nuances of his mentor Jan Sedivka, Sitsky honoured his musical grandfather and kindred spirit Ferruccio Busoni –both through his expresive pianism and particularly in his compositions. Busoni’s Sonata itself pays homage to certain composers before him –Beethoven, Bach, Mozart and others.

Sitsky composed his “Opus One” violin Sonata on board the S. S. Orsova in 1958, en route to San Francisco. Written for the violinist from the ship’s band, (who used the psuedonym “Manikin” instead of his real name “Menuhin” which he felt he couldn’t live up to) Sitsky named his Sonata “Opus One” thus relegating all his previous work to juvenilia. After the long sea voyage, Sitsky arrived in San Francisco to begin studies with Busoni’s most famous student Egon Petri, a meeting that changed the course of Sitsky’s musical life.

It would be difficult to think of a violinist better suited to this work than Frømyhr. Effortlessly opening the Prelude with double stopped gestures, Frømyhr’s quasi-cadenza figures were breathtaking. In the stately second movement, named “Improvisation, heard in the distance,” Frømyhr drew haunting cedar tones from the violin. His muted sotto voce opened out into a wide timbral palate, from Gypsy inflections to the left hand pizzicato that characterises this work. Frømyhr’s virtuosity was clear in the subsequent March. This movement launches with abrupt articulation –jeté, battuto and accented down bows. While the Prelude evidences the strong influence of Bartok, the March diverges to pointillism. Through sets of variations and the Postlude, Frømyhr brought the first of Sitsky’s mature works to a close with a poetic vibrato, birdlike trills and double stopped acciaccaturas.

Introduced by Sitsky as “the closest I ever came to minimalism, which I normally detest”, his Fantasia No. 11, “E”, was inspired by noticing that the name of a student from the former Canberra School of Music Jazz School contained only one vowel. This refined and mature work obsesses around the single note E and evokes a Near Eastern aesthetic. Bringing an astonishing range of colour from the piano, Sitsky conjured a melancholia, a kind of musical saudade, with single notes ringing out of the texture like bells.

The dramatic second movement shattered the serenity of the opening. A mood of foreboding was established with tremolando chords, the lightness of the first movement returning only briefly, and only then to make the darkness seem darker. Sitsky’s familiar tritone outlines rose in tense utterances, harplike peals building to angry palm and elbow clusters.

In the Paderewski-like closing movement, Sitsky’s thunderous chordal passages open to a dignified melody in single notes. Gradually the background was filled in like an orchestra supporting a lone soprano. Like much of Sitsky’s music, the opening and closing movements of this work are quiet; something the composer sees as a journey that begins and ends in light.

The grand finale of this concert was Frømyhr and Sitsky’s performance of Busoni’s rarely heard Sonata No. 2 (also nicknamed Opus One). Like Sitsky’s “E”, this Sonata is also centred on a set a variations. From the opening undulations in the piano, this work is quintessentially Busoni. One can immediately recognise the extended tonality, a harmonic richness that has not been explored since Schoenberg. Subtle chordal shifts give this work the gravitas of Bach, the poetry of Beethoven, while at the same time pre-echoing the sophisticated language of Webern. Through its classical cadential structure, Busoni acknowledges the past without being bound by it.

Throughout the Langsam opening, Frømyhr and Sitsky evoked diabolical atmospheres through recurring dotted rhythms, a device Busoni later associated with the appearance of Mephistopheles in his Doktor Faustus. These passages of hellfire rhythm and soaring violin, recalled Mozart’s Don Giovanni being dragged to hell. But the portentous opening, with its often claustrophobic sonorities, opened out onto a soaring violin like the sun moving from behind a cloud –a masterful shift achieved without resorting to simple tricks of consonance and dissonance.

In the Presto, Busoni again evokes the devil through galloping rhythms like those from the Wolf’s Glen scene from Der Freischütz. Here Sitsky’s dramatic timing and Frømyhr’s expansive vibrato commanded the rise and fall of tension over a long duration, like church architecture. A return to stately elegance followed this explosive second movement. Here Sitsky transformed the piano into a church organ, a hint of foreboding preserved in sustained pedal tones.

Frømyhr’s sustained and poetic top register floated over the piano as the music opens onto Bach’s chorale “Wie wohl ist mir”. Recalling its earlier classical structure, the chorale melody is carried by the piano while the violin weaves around it in ornamentation –a choir and its cantor. This austere movement is more than a simple nod to a previous composer, more than quotation; here Busoni presents true transcription: the blurring of lines between one composer and another.

Frømyhr and Sitsky’s Busoni was almost too beautiful to endure at times. Frømyhr’s deep understanding of Busoni’s harmonic devices was evident in his subtle changes of tone and Sitsky produced consistent clarity of line even through the densest counterpoint (sometimes producing three or four distinctly different dynamics at once). Busoni’s first great sonata reveals where music was heading before being diverted by the Second Viennese School, the road not taken by Western art music. It is worth noting that this 1901 work, like Sitsky’s entire oeuvre, begins and ends in light. Certainly, on a larger scale, Sitsky’s “Opus One” sonata for violin can be seen as a journey beginning in light. One assumes that Sitsky’s last period works will do the same –end in light to close the circle. I, for one, hope to hear at least another twenty years of music from Sitsky first.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply