IT’S not often a major exhibition is described as necessary, vital, essential and demanding of attention, but so it is with the newest exhibition at the National Gallery.

“The national picture: the art of Tasmania’s Black War” is a look at a violent part of Tasmania’s history through the medium of art but has, as one of its major themes, the subject of “conciliation”.

“But notice the difference between that word ‘conciliation’ and ‘reconciliation’,” says Prof Tim Bonyhady from the ANU, co-curator with Greg Lehman, from the University of Tasmania. “Conciliation” suggests placation of an inferior, “reconciliation” suggests reuniting, a two-way activity.

Much of the new exhibition surrounds the historical figure of George Augustus Robinson, builder, preacher and self-styled “conciliator” or worse, “pacificator” (the word appears on his gravestone in Bath) of the Tasmanian Aborigines after the so-called “Black War”, whose mission it was to round up the Aborigines and resettle them on Flinders Island.

Robinson befriended Truganini, to whom he promised food, housing and security in exchange for help in forging an agreement with the Big River and Oyster Bay peoples. Undoubtedly a gifted man, Bonyhady says he had a grasp of Aboriginal languages and compiled valuable word lists.

Robinson, it turns out was also a visual entrepreneur who understood how important pictures could be. He was a collector and the provenance of three of the surveyor-general George Frankland’s now threatening “proclamation boards” can be traced directly back to Robinson. Ironically these boards derived from an idea that the “natives” would respond to pictures.

The key artist in the exhibition is Benjamin Duterrau, a minor figure from London, who arrived in Tasmania in 1832.

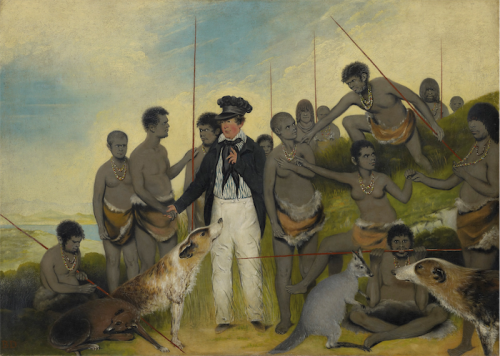

Duterrau conceived of his grand project, a “national picture”, that would depict Robinson’s “Friendly Mission” in painting, sculpture, prints and drawings, preferably for public acquisition.

He pictured Robinson as a solitary, noble white man among wild Aborigines, relying solely on persuasion. But this often-shocking exhibition shows how in fact, although he usually went unarmed, he engaged local Aborigines to do his “persuading” for him and some did carry weaponry.

The show, developed in partnership with the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, is “extraordinary because it is very rare”, Bonyhady says, giving full credit to the former NGA director Ron Radford and his successor Gerard Vaughan for recognising that these Tasmanian paintings were not just of regional significance but part of a major national narrative.

With the arrival of figures such as John Glover in Tasmania, Hobart had been the centre of art in colonial Australia for a time, but from the purely aesthetic point of view, Bonyhady and Lehmann have had to contend with art purist detractors.

“Duterrau was not a sophisticated artist,” Bonyhady says. “His lack of skill, however, was compensated for by their scale and ambitious nature.”

His huge canvases of “savages” in stereotypically aggressive poses are imposing and in the case of “Native Taking a Kangaroo 1837”, where a “European” dog is engaged in the process, are indicative of cultural changes.

Other artworks, such as the busts by Benjamin Law, paintings by WB Gould and Thomas Bock, and photographs by Pierre-Marie Alexander Dumoutier, do look as if they are representations of real individuals.

The exhibition is not confined to paintings. Rare, early works by Tasmanian Aboriginal people, ceramics and Aboriginal oral history sit alongside settlers’ representations of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and 21st century political responses of artists such as Julie Gough and Ricky Maynard.

Bonyhady began his career when he became a junior curator in Tasmania after having written a paper on early Tasmanian art. It is familiar territory to him, but he agrees that despite signs of resistance in the faces of some portrait subjects, the exhibition is “incredibly sad”.

“The national picture: the art of Tasmania’s Black War”, NGA, until July 29. Free entry.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply