INTERESTING times we may be living in, but even in the face of recent Australian political upheavals, one of the biggies remains the day Gough stood on the Parliament House steps and declared “nothing would save the governor-general” following Sir John Kerr’s dismissal of him as prime minister.

It was November 11, 1975, and the metaphorical shots that rang out that day reverberated long and loud.

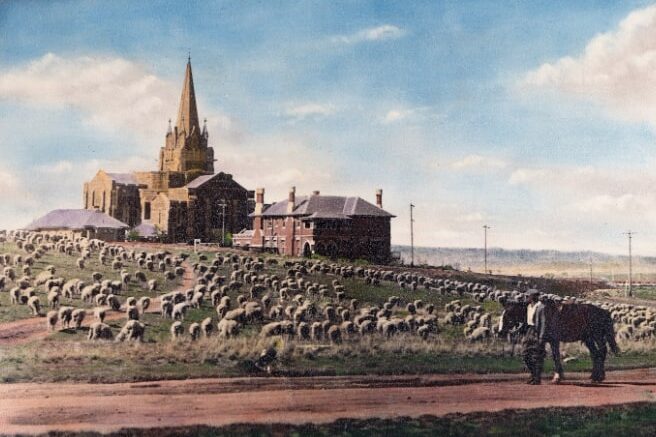

One of the most astonishing developments would be dragged out over another three years in, of all places, Queanbeyan.

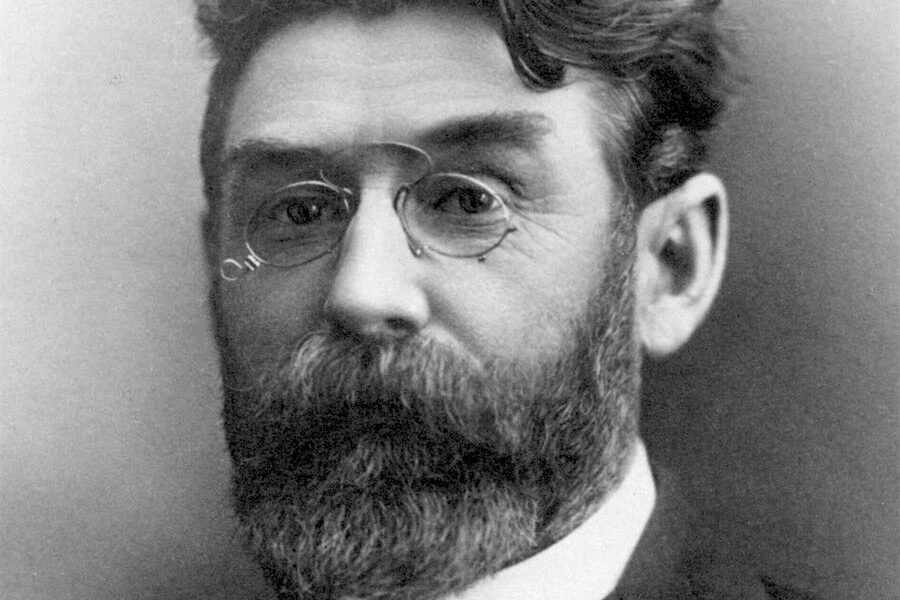

In the Court of Petty Sessions of the NSW border town, which had itself barely achieved city-status, charges of “conspiracy to deceive” brought against ex-PM Gough Whitlam, his once Treasurer Dr Jim Cairns and former Attorney-General and, by then High Court justice, Lionel Murphy, were ultimately dismissed on Friday, February 16, 1979.

The “Loans Affair” as it became known, sensationally saw a criminal prosecution launched by an otherwise unheralded Sydney solicitor, Danny Sankey – essentially equating to a private citizen taking on political privilege – only a matter of weeks after the controversial Whitlam sacking.

Sankey alleged that an attempt to source $US4000 million in overseas borrowings by senior Ministers in the Whitlam government (originally also including Minister for Minerals and Energy, Rex Connor, who died in 1977) had involved the “deception” of Governor-General Kerr on the basis it was for “temporary purposes”.

Sankey also claimed a breach of the Commonwealth Crimes Act, specifically, a contravention of an historic financial agreement between the Commonwealth and the states. This would be taken to, and eventually deemed invalid by, the High Court in 1978.

The rest of the drama though, would continue just over the state-territory line and both the defence lawyers and the sitting magistrate, Mr Darcy Leo, had already advanced the question of “why Queanbeyan?”. Proximity to Canberra was the answer, and hence the streets of the town came to be lined with more legal silk, politicos and newshounds than seen in 140 years of law and order there.

Adding comic pathos, almost from the outset, the Queanbeyan Court House of 1861 was in the throes of being torn down to make way for a new, more “brutalistic” concrete one to be erected in its place.

Proceedings – and furniture – had to be moved to makeshift digs in the nearby, similarly poorly provisioned Fallick Hall. It included, by needs, a much-extended bar table, cobbled together with a number of the old ones laid end-to-end that, according to the “Gang-Gang” column of the day, (yep, around even then), made it “longer than those found in the average public house”.

The allegation of a conspiracy inevitably generated enough counter-conspiracies to fill a season of “The X Files” (never mind almost as many appeals as days actually spent in court). Some claimed the prosecution was a set-up by the NSW Liberal Party, while the man who would become PM, Malcolm Fraser, was criticised that the timing conflicted with the impending, now necessary, election.

The fact Cairns would be dismissed for a “related matter” and Connor, for “misleading parliament” (further in-depth details can be found at naa.gov.au) only encouraged conjecture. Later speculation as to alleged interference by outside entities also meant disquiet was anything but quiet.

And still it went on: 13 months after being brought to court, in January, 1977, Leo disqualified himself from hearing the matter due to an associated defamation action against a newspaper.

No less than the NSW Chief Stipendiary Magistrate, Murray Farquhar, would take his place on the Queanbeyan bench, albeit, briefly. An appeal saw Leo resume his position, the court ruling that he should be released from other duties in order to hear the case continuously – clearly, the delays and perceived shenanigans were wearing thin.

Eventually the leviathan it had become ground to a stop, Leo finding there was no “overt act to deceive” and, with insufficient evidence to commit the defendants, all charges were dismissed.

Sankey would claim no regrets – except for the substantial hit to his hip pocket (and his pledge to go to prison rather than pay costs would continue into another year) – and maintained he had no links to any other party, political or otherwise: “I am in it on my own”.

According to his own defence team, the solicitor had “undertaken the prosecution from the highest motive” and his actions had ensured “the Australian people were now aware of the facts”.

It would be Whitlam who’d have the last word (well, almost). As he stood on a different set of steps on that February day, his Queanbeyan pronouncement was as quotable as his Canberra one of three years earlier:

“The comedy is over. The whole proceedings have been a farce, and a protracted one”.

For additional developments, controversies, and historic detail, see nichole2620.wordpress.com.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply