HAVE you ever noticed how men sit on public transport with their legs askew, occupying other people’s space, while women take pains to keep them close, or slightly to one side?

Borzello is just off the plane from London and we are looking at a reproduction of a portrait in which the subject of the portrait has her legs well apart and a slightly quizzical look on her face, very far from the conventionally modest and restrained visage in traditional portraiture. “Women don’t do that,” she says. Or at least they didn’t.

These are the kinds of matters that shall be raising in her talk, “Facing the truth?” tonight, the NPG’s Annual Lecture and Borzello, a noted British art historian, goes so far as to suggest that we should become ‘detectives’ when we look portraits and not just accept what we see at face value.

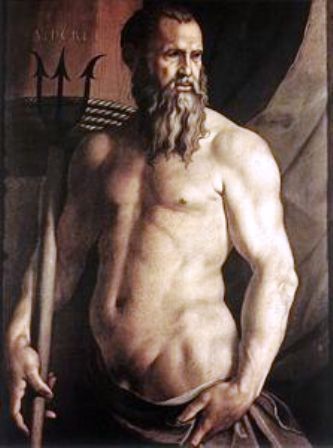

Detectives? Well, take Bronzino’s famous 16th century painting of naval hero Andrea Doria as Neptune, naked from the waist up, middle-aged, attractive but developing a paunch. What can be read into it? And does that trident mean, apart from telling us which Roman god is being portrayed? We can surely find meanings in that.

Nudity in portraiture is another question that thing on her mind of late. Until fairly recently, nude figures are generalised in art, she notes, bland features and usually no name attributed to the sitter. Even Lucien Freud rarely identified his nude subjects.

But that’s all been changing. Consider the US artist Alice Neel and her 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol, again naked from the waist up and looking exceedingly vulnerable after having been shot. Here we know the name and the fame of the sitter, but the portraitist gives a new view.

Tonight, though she may change her mind, Borzello thinks she’ll be talking about the language of portraiture. She strongly rejects the view that it’s just up to the viewer and the poor troops are “just a likeness,” arguing that there are symbols and seems to be read into the colours, the size, the aspect and the background.

Traditionally men have been portrayed with “important” things around them, symbols of power, a portrait is set in a library, learning, while women are left with children or, even if the subject is a fine musician, a musical instrument is just an accessory.

An obvious exception is the famous, Ditchley portrait of Elizabeth I, trapped in her elaborate embroidery, yet standing on a map of Britain, an accessory symbolising power. In complete contrast she notes Ralph Heimans’ recent portrait of Queen Elizabeth II recollecting her coronation, and surmises that her grim faced suggests she’s had just about enough of power.

Borzello suggests that as become detectives we try the trick she has discovered—try reading the paintings without looking at the captions. I decide to do it from now on.

Of course she’s become something of a social historian in her work, so as a detective, she’s a bit further down the track than most others. She has noticed that black people didn’t turn up important painting a serious subject until recently unless they were the “little black boy” of the servant classes in, say 18th-century paintings. We pause in front of Guy Maestri’s 2009 portrait of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, which Borzello has obviously never seen before, and she notes the subtlety of the colour, the size, the power and the dominance of the sitter. Times have changed.

Going back to Paris in 1909, she comments on English artist Gwen John’s portrait of Fenella Lovell, bony, drooping breasts, secretive eyes— without a touch of eroticism associated with the female nude.

Another thing that she’s been thinking about is the portrayal of old women. While in the history of portraiture, some of them fare better than their younger counterparts, nude elderly women are pretty much always depicted as old hags.

But Borzello’s talk this evening will not be focusing on nudity, though her latest book is “The Naked Nude.” Her intent is rather focus on the language of portraiture and help us all to become detectives. And that sounds like fun.

National Portrait Gallery, Annual Lecture, “Facing the truth?” by Frances Borzello, at the NPG today, Thursday, July 11 at 6pm. Details at portrait.gov.au/site/programs_category.php?categoryId=67

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply