IT was 150 years ago and more than a decade before Ned Kelly would earn infamy for killing three Victorian policemen that the worst massacre of police in our history took place at an isolated area known as the Duck Pond at Jinden, halfway between Canberra and the far south coast.

And yet, this largely remains one of the least known occurrences in all of Australia’s often glorified bushranging past and of the death of multiple officers in a single act of performing their duty.

In an effort to rescue the details from historic obscurity, the Monaro Local Area Command of the NSW Police has unveiled an official memorial marking the spot and direct descendants of the parties involved were among those present.

Today the remote location essentially remains as it was on January 9, 1867, when four “special police” constables were gunned down by the notorious Clarke Gang, widely held to be the “bloodiest bushrangers” ever to take to the bush under arms.

Led by brothers Thomas and John Clarke, they’d killed 25-year-old Constable Miles O’Grady on April 9 the previous year. In total, while lasting less than two years, their rampage from Braidwood to the Monaro encompassed up to 100 crimes, including a potential seven murders.

So high-profile were their misdeeds, the Felons’ Apprehension Act of 1865 was invoked against Tommy and his uncle, Pat Connell, allowing the public to shoot them on sight, while Colonial Secretary, Henry Parkes, established – contentiously – an “independent” force intended to bring this “reign of terror” to an end.

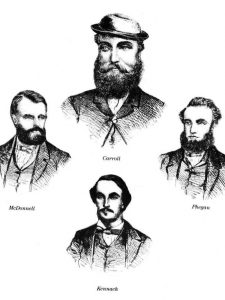

John Carroll and Patrick Kennagh, both prison warders, and Eneas McDonnell, also a warder and ex-policeman, along with ex-convict John Phegan, were secretly sent to Braidwood and “sworn in as special constables for the district”.

According to Araluen author, Peter C. Smith, who in 2015 produced the most comprehensive book written on the Clarkes, it was as the troopers were heading back to Jinden Homestead that they were ambushed. All were shot dead.

“Constables Carroll and Kennagh were clearly in a kneeling position. Whether it was intended as an execution, or if the men were pleading for mercy or saying their prayers remains unknown.”

“It was a tragedy that shocked the colony,” says Smith. “But along with being victims of the bushrangers, the special officers then became the victims of politics – a government that would take no responsibility for the creation of a force outside a force, and the police who were angered at the suggestion they were unable to adequately deal with the situation.”

It would take another two months before the Clarkes would finally be tracked down – still in the vicinity of Jinden – and after being taken to Nelligen, where they were chained to a tree that continues to stand in mute testimony to their litany of crime, they were removed to Darlinghurst Gaol in Sydney.

There, on June 25, 1867, Tommy at 27 and John, only 21, met their end on twin gallows, the sentence handed down for the single act of shooting (with intent to kill) Constable William Walsh during their final stand.

As Smith sums it up: “There was no need to try them for the other murders, they’d been sentenced to death and dead was dead.”

Sensationally though, until their very last moments, the brothers would protest their innocence in relation to the deaths of the officers of the law (though if not they, then who?), and this continued to fuel speculation and distort the events of the day.

Chris Phegan is the great-great-nephew of the fourth member of Parkes’ police, John Phegan, and he says that for many years his uncle’s story was virtually lost to the family with details obscure and largely inaccurate.

“My father told me the story when I was young, but in his version, we were related to a bushranger. Only much later did we learn the truth of John Phegan’s involvement and fate,” he says.

After 50 years of research into the Clarkes, their associates and their victims, for Smith it’s the marking of the site on the same date, 150 years later, that’s significant.

“Until today , the sacrifice those men made had never truly been acknowledged.”

Nichole Overall is a Queanbeyan-based journalist, author and social historian.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply