Arts editor HELEN MUSA previews the national Gallery’s summer blockbuster “Matisse & Picasso”.

A COMPLEX mix of rivalry and admiration between two giants of 20th century art is at the heart of the NGA’s big end-of-year blockbuster, “Matisse & Picasso”.

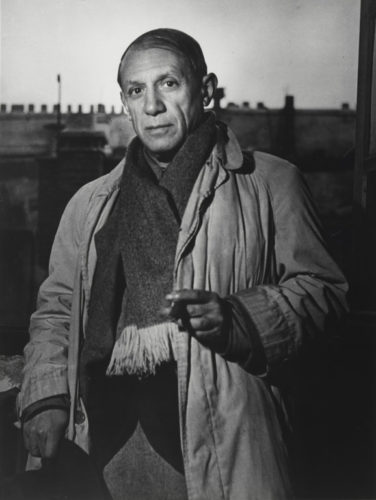

Not just a visual feast, it will also serve to tell the story of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso’s turbulent yet fruitful relationship, which ended with Matisse’s death in 1954, when Picasso said, “Nobody ever looked at Matisse’s work as thoroughly as I did. And he at mine.” Even while alive, they were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

The show involves loans from Musée Picasso in Paris, Tate in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, private lenders in Australia, England and France and the gallery’s own considerable collection.

Both the Matisse and Picasso estates are very strict about reproduction rights, so it’s been “tricky”. Matisse is out of copyright in Australia with some caveats, but Picasso’s works are still within copyright, so she says, “we touched base with them years ago and have been working very closely”.

The exhibition has been three years in the making. With 250 works and costumes and designs by both artists for the Ballets Russes drawn from the NGA’s own collection, and Matisse’s paper cuts from the 1930s when because of health reasons he couldn’t paint anymore, it’s likely to be a sumptuous looking show.

The exhibition is chronological, covering the period from 1906, when the two artists met at the Paris salon of Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas and became lifelong friendly rivals, until Matisse’s death in 1954. Maxwell stresses that it does not venture into Picasso’s later life and art during the 50s, 60s and 70s.

“Matisse & Picasso” begins with a very small room highlighting a few works by each, indicating where they were at the time they met.

At that time, Matisse was the leader of the notorious Fauves (“wild beasts”) artists whose works featured wild colours, whereas Picasso was a child prodigy who had moved to Paris and was enjoying the cabaret culture – a bit like Toulouse-Lautrec or Degas.

The two men could hardly have been more different, yet they instantly if grudgingly admired each other. They met regularly at the Steins’ Saturday soirées, where reputedly most people came to see their collection of Cézannes.

The second room in the exhibition in fact covers the influence of Cézanne, who made a huge impact on them, Maxwell says: “They both thought Cézanne was incredible and proceeded to unpack his work.”

But while slightly older Matisse lashed out with colour, Picasso turned to Cubism. Matisse openly despised it at first, although later he was to come around to it.

The exhibition moves into the popular area of the Ballets Russes’ costumes, which sit outside the formal chronology of the show, exhibiting Matisse’s 1920 costumes for “The Song of the Nightingale” and Picasso’s for “The Three-Cornered Hat,” both from 1919-20.

Another area of focus is the way both artists ventured into exoticism. Picasso’s African-influenced period began after he saw African artefacts in the Parisian ethnographic museum during 1907. Matisse spent seven months in Morocco from 1912 to 1913, which led to about 24 paintings, numerous drawings, and his famous “odalisque” paintings.

“We see how divergent their approach was in depicting women, but we don’t always see a direct cause-and-effect in their influence,” Maxwell says.

“For instance, something that Picasso said in 1912 will trigger Matisse in the 1920s or 1930s. The exhibition goes back and looks at what they have done and the way they changed their minds.

“Plainly Matisse thought Cubism was complete crap, but he changed his mind, and Picasso started out monochrome, but after viewing Matisse he appeared to say ‘I could do that, I could do with a bit of colour’.”

As for the look of the show, Maxwell says, “we are going modern. This show is about a relationship but it’s really about the art they produced, so it’ll be a pared-back colour palette, pale light blue and light pinky mauve, to work with the works and not overwhelm them.

“Such colourful things, such different things over that 50-year period… We really want the works to speak to the viewers.”

“Matisse & Picasso”, National Gallery of Australia, December 13-April 13.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply