It’s the 80th anniversary of Canberra’s worst air disaster. “Yesterdays” columnist NICHOLE OVERALL looks at the mystery surrounding the crash.

IT could still pass as a semi-rural route skirting Canberra’s northern boundary and most commuters pay no heed to the solitary sign and locked gate indicating the location of an aviation disaster that shook a nation.

Eight decades on, the mystery and the controversies surrounding what former NSW politician-turned-author Andrew Tink described as “the plane crash that destroyed a government”, linger as a vapour trail in its wake.

At the summit of the rugged ridge where a RAAF Lockheed Hudson bomber (A16-97) inexplicably plummeted to earth on a sunny winter’s morning 80 years ago, there’s a rarely seen stone monument to the 10 victims onboard. Virtually incinerated on impact, they included some of the country’s most prominent members of a government then firmly on a war footing.

As August 13, 1940, dawned, it had already been anything but ordinary.

Almost a year into a second world conflict, the German Luftwaffe, intent on invasion, had launched its first major air offensive in what became the Battle of Britain.

Far from the skies over England’s south-east coast, near 11am on that day, “about two miles north of the old NSW town of Queanbeyan” along the quiet road between it and the Australian capital, a huge aircraft was seen flying barely a few hundred feet from the ground.

As it crested a rise, over which was the Canberra aerodrome, one witness would attest the plane banked sharply left and then “turned completely over sideways and hit the ground.” It was consumed by flames so hot, parts of it melted.

An unfathomable, tragic accident. Or was it?

The press reported “ideal flying conditions”. Rumours circulated that someone other than Air Force pilot, Flt-Lt Bob Hitchcock, was at the controls (as well as on his level of expertise). There arose questions of why so many significant political figures were travelling together.

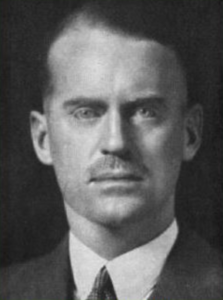

The manifest comprised three senior ministers on their way to attend a Cabinet meeting: Geoffrey Street, Minister for the Army; Minister for External Affairs, Sir Henry Gullett; and Minister for Air and the RAAF, James Fairbairn.

Others present were the chief of the General Staff, Sir Cyril Brudenell White, his liaison officer, Fairbairn’s private secretary and four RAAF flight crew.

It seems the potential as an act of war – sabotage through espionage – was only briefly entertained, but that didn’t stop the conjecture.

By that very afternoon there appeared stories of “hand-of-fate” proportions, involving others who were meant to be on the plane.

Ministerial assistant Murray Tyrrell, a later alderman on the Queanbeyan Council, had flown with Fairbairn and Gullett to Canberra in the same plane the previous week. On this occasion, he apparently caught the train instead.

As detailed by another author, Dr Cameron Hazlehurst, a shaken Tyrrell presented the devastating news to the Prime Minister, describing Robert Menzies’ reaction as “absolutely stunned”. Unbeknown to the other, the PM had himself been intended for that flight. One to avoid flying unnecessarily, he’d also gone by train.

In the face of a host of inconclusive inquiries, recollections and analysis still vary dramatically.

Rather than “nose down” it seems the bomber “pancaked”; an attempt to land on the only spot of ground cleared of everything but a large log – which ripped away much of the underbelly.

Other persistent speculation involves the degree to which the tragic affair undermined Menzies’ wartime government.

A week after what the PM would refer to as “that terrible hour”, he’d call an election for September 21.

The hung parliament outcome resulted in further instability. Just a year later, Labor’s John Curtin would prevail.

While some downplay its importance, Andrew Tink argues that the event directly contributed to Labor taking power.

“The absence of some of Menzies’ most loyal supporters was pivotal,” he explains.

“In addition, Gullett’s seat of Henty was won by an independent, Arthur Coles, who ended up holding the balance of power. He backed a Budget amendment that amounted to a vote of no confidence, leading to Curtin being commissioned as the prime minister. Had Gullett not been killed, none of that would have occurred.”

Controversially, Andrew also posits that it’s not inconceivable that Minister Fairbairn, an able pilot but with no experience of the notoriously finicky Hudson, had pulled rank on Hitchcock and taken over command.

“A week before the crash, Fairbairn had discussed how he intended to practice landing Hudson bombers which had a ‘nasty stalling characteristic’ that he felt could be dealt with by better handling of the throttles,” says Tink.

“In light of what happened, I think this is quite damning.”

Furthermore, Andrew points out that the premature removal of the badly burned bodies from the scene meant “it was impossible to tell where they had been in the wreckage.”

Now known as the Fairbairn Pine Plantation, as the wind whispers through the forest, it’s a place that makes you feel you’re miles from anywhere. And yet, beyond the dense trees on one side are the bright lights of the heart of the Australian Commonwealth; on the other, the bustling regional city of Queanbeyan.

Erected 20 years on from what was a national tragedy, the memorial sits within a small open area, surrounded by five eucalypts. According to the National Capital Authority, the idea the trees “may be the vestiges of the original heavily wooded hilltop”, is dubious in the face of the reported intensity of the fire.

A victim of thoughtless vandalism over the years, the area subsequently came to be fenced off and locked.

The definitive reasons for the crash continue to elude. If the fog of war clouded things then, now the passage of time seems to have done the same, awareness of the impact of the disaster fading like the very sign that points to it.

- Once a regular haunt for teenagers, it’s also claimed as one of Canberra’s “most haunted” – from temperature fluctuations to cars stalling and the apparition of a woman. Historically, it is linked with other less explored events, and that’s a tale for another column.

More at anoverallview.wixsite.com/blog

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply