“Yesterdays” columnist NICHOLE OVERALL looks at the remarkable role and service here and abroad of local nurses during World War I.

HORRIFIC wounds, the ravages of disease and tortuous deaths: they experienced first hand the worst of what war brings.

Not the men charging into battle, but the women virtually behind them. Those staffing military hospitals and a medical system that evolved to deal with broken bodies in the midst of equally destroyed landscapes.

In World War I alone, Canberra – in 1914, barely a year old – could lay claim to a handful of such pioneers. Historian and author Patricia Clarke, based in the capital, has extensively researched these women at war.

With 60 years of involvement with the Canberra & District Historical Society, including time as president, Patricia was asked to write on the topic for an online exhibition for the Australian Women’s Register.

“I was honorary editor of the Historical Society’s journal for 14 years, but until I began researching Canberra in World War I, I was unaware of the wonderful treasures we have in the stories of the nurses who were associated with our region,” says Patricia.

The roll call features matrons from the hospitals at Queanbeyan and the new Royal Military College, Duntroon, as well as three women from the same family.

Another would be written about after the war as “The Mystery Matron” – a century ago appointed as head of the Canberra Hospital on its 1921 re-opening.

All were single and under 40, as per requirements – or at least so they said. While their motive was primarily to care for “our boys”, each saw active duty in Greece, India, England and on the Western Front.

From Yass to Queanbeyan, Bungendore to Braidwood, hundreds of husbands, sons, brothers and fathers left to play their part.

Local women and Canberran wives, those married to the likes of the then Territory Administrator, the Duntroon commandant and graziers of the ilk of the Cunninghams of Lanyon, would take up the fight on the homefront. Involved in raising funds, providing “care” packages and running farms and businesses when facing few other options.

A prominent example: shortly after Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, wife of the governor-general, commenced her mid-1914 efforts to establish the Australian Red Cross, Queanbeyan formed a branch.

Led by the mayoress Agnes Moore, wife of town mayor Richard Moore, and mother to a son who’d be killed at Villers Bretonneux, France, in 1918 (Walter, a gunner with the 5th Field Artillery). Queanbeyan remains among the longest continuously operating Red Cross branches in the country.

More than 3000 Australian women signed up, taking an even larger leap into the abyss of war. According to the Australian War Memorial, eight received Military Medals for bravery and 25 lost their lives.

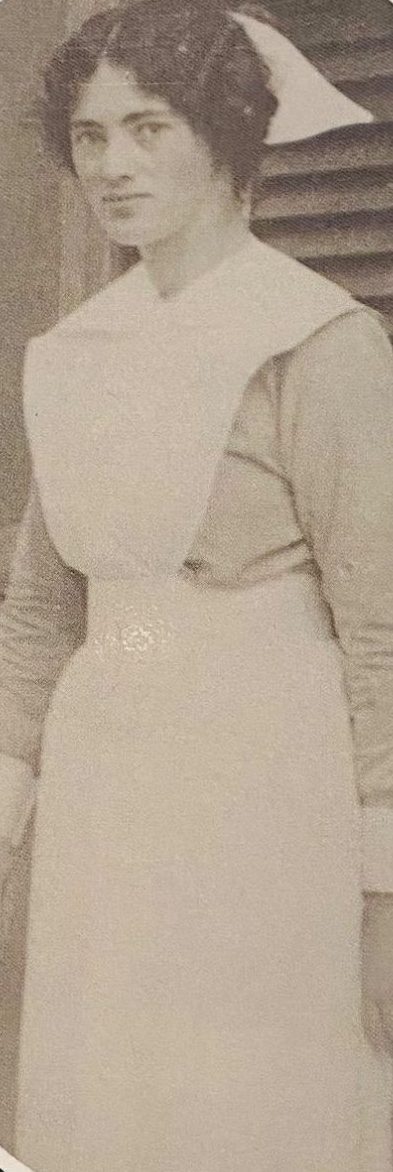

For six months from October 1914, Patricia Blundell had been matron of Duntroon’s hospital.

A surname associated with an 1860s stone cottage that sits upon the now northern shore of Lake Burley Griffin, Patricia hailed from a Melbourne clan.

She was among the first Australian nurses to arrive on the Greek island Lemnos to deal with the fall-out of nearby Anzac Cove, of which Patricia Clarke wrote: “The tent hospital was only partly constructed, the wounded were lying in the mud and there were critical shortages of not only medical supplies but food and water”.

Sister Blundell survived it – and more. Travelling back to Australia in 1918 aboard the SS Barunga, with more than 800 of mainly sick and wounded, she escaped when it was torpedoed in English waters.

At the beginning of 1917, the nurse had been posted to “a tent hospital on desolate and windswept sea cliffs” near Boulogne, France.

Flora Gallagher, of Browns Flat, between Queanbeyan and Bungendore, was there at a similar time.

A trained nurse from 1909, Flora was the first of the “Gallagher Girls” to enlist, followed by her sister Evelyn, and their niece, Janet. All returned safely to Sydney by the end of 1919.

“Since 2016, I’ve been trying to have the three Gallagher nurses commemorated by the ACT Place Names Committee,” says Patricia Clarke.

“Preferably at or near Browns Flat, which is now within the ACT boundary.”

Also confirmed by Patricia, Gladys Boon was a Queanbeyanite by birth, despite nominating Goulburn on her enlistment records.

Gladys’ maternal grandfather was the early pioneer Thomas Southwell, of Parkwood, Ginninderra.

She trained and became head nurse at Orange before enlisting in 1917, and where she’d return at the end of 1919, seeing service in Salonika, Greece.

Another locally linked was Alice Robinson, a well-regarded former matron of Queanbeyan Hospital and briefly at RMC Duntroon. She served from 1915 to 1918, re-settling in Melbourne.

One who remained in Australia, but did more than her duty was Queanbeyan’s Mary O’Rourke.

Nursing in Sydney from the outbreak of war, Mary cared for the shattered soldiers shipped home. So was she known for meeting the boys from her hometown to farewell them as they set sail into the unknown.

Some of those returning brought with them the infamous Spanish Flu. Mary was infected, but managed to recover.

Possibly the most intriguing on the local list is Gertrude Lawlor, the “Mystery Matron”.

“Nearly six foot tall with black hair, blue eyes… and a fiery temper,” Gertrude claimed herself English-born, from a “decorated military family”, and a widow. Except she was none of those things.

She was though, a highly qualified nurse.

By early 1917, Gertrude was matron/dispenser of the Canberra Hospital – the tiny facility of eight beds opened only three years earlier. On its closing in October of that year, she joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS).

When the hospital re-opened in 1921 – Canberra’s population then almost 2600 – Gertrude was back from having served in India and resumed her position.

She resigned seven years later after continuing battles with staff and government officials. She died in Dublin in 1959.

It emerged Gertrude Lawlor was actually the daughter of an Irish farmer who for reasons known best to herself, left all behind including a broken marriage and an infant daughter, re-inventing herself in Australia come 1913.

Inevitably, war can create many myths. What’s beyond doubt is that each of these remarkable women were trailblazers who deserve the recognition not always readily apparent at the time they also willingly gave of themselves in service to King and country.

More of Nichole’s history detective work at anoverallview@wixsite.com.blog.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply