The major contested change is the extent to which the legislation widens employees’ right to bargain with multiple employers, writes MICHELLE GRATTAN.

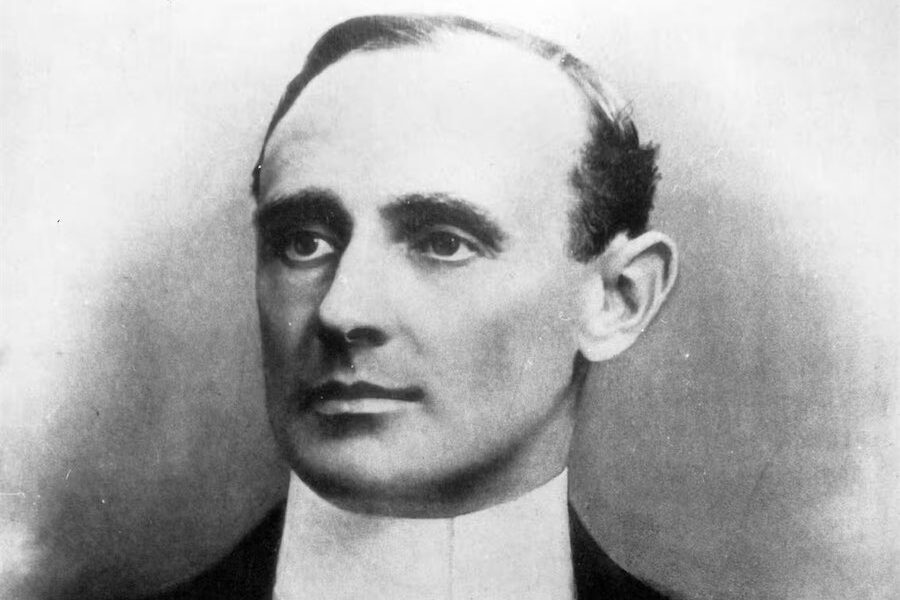

PETER Reith would have appreciated the irony. In the week that the former industrial relations minister died, federal politics was yet again consumed with a highly charged debate over workplace changes.

Industrial relations is one of the perennial fault lines in Australian politics. As some battles get settled, fresh ones arise, often involving similar issues, in the enduring argument about growing and sharing the economic pie.

When he held the portfolio in the Howard government, Reith was both negotiator and warrior. In 1996 he and Cheryl Kernot, then leader of the Australian Democrats, who were the crossbench power wielders of the day, stepped their way to a compromise on a package of reforms.

Later, Reith was a tough player in the bitter employer-government assault on union power on the waterfront.

Reith had long gone from parliament by the time John Howard’s radical WorkChoices law became central in bringing down the Coalition government.

In the next turn of the industrial relations wheel, WorkChoices was scuttled by the Rudd government, with Julia Gillard the minister.

The Albanese government’s “Secure Jobs, Better Pay” omnibus bill, which passed the House of Representatives on Thursday, is broad in scope and the stakes are high for the key players in this latest IR test of strength.

The major contested change is the extent to which the legislation widens employees’ right to bargain with multiple employers.

Labor is delivering to the union movement with this bill, which also includes the scrapping of the Australian Building and Construction Commission, a body hated by the unions (and already defanged by regulation since the election).

The government used its jobs summit to prepare the way for a move on multi-employer bargaining. This was something of a ruse – there was never going to be a business-union consensus on this (although a section of small business took the bait at the summit). But the tactic left business wrong-footed.

Labor is desperate to pass the bill through parliament before Christmas. It argues the legislation’s crucial objective is getting wages moving so it’s needed ASAP. More pertinently, Labor is under intense pressure from the unions. It also wants to deny business time to run a campaign.

The government needs one upper house vote over and above those of the Greens to secure the bill in the remaining sitting fortnight of the year.

Enter David Pocock, regarded as the most likely crossbench vote for the legislation (although, in theory, any Senate crossbencher could move into the frame).

Pocock is a progressive in his views and his support base, but he won his ACT senate seat from the Liberals, so at a constituency level he is under conflicting pressures.

He has urged that the bill be split, enabling more consideration of its contested parts. For obvious reasons, the government doesn’t want it broken up.

Crossbenchers in the lower house could not affect the outcome there but weighed into the debate. Their contributions were a reminder that on certain issues some “teal” MPs are more right-leaning than left-leaning.

Sophie Scamps told parliament the “omnibus” bill bundled together many “excellent policies” with “the more controversial ones”. “This has created a Sophie’s choice when it comes to voting.”

Another NSW teal, Allegra Spender, urged provision for an independent review after a year. Workplace Relations Minister Tony Burke preferred to leave that matter until the bill is in the Senate. Burke said he didn’t want to adopt such a review in the lower house and then “in Senate negotiations, we end up with a different independent review”.

The cynic might say the government is leaving room for Pocock to have wins of his own in the upper house negotiations.

Of the teals, Zoe Daniel and Monique Ryan voted in favour of the bill, while Spender, Scamps and Kate Chaney voted against.

The government’s determination to speed the bill’s passage has strengthened business’s hand. Burke has given a number of concessions for employers.

A significant one is that votes of workers (to seek a multi-employer agreement, to strike, or to accept an agreement) would be taken at the individual business level, rather than on an overall basis. This would prevent workers in larger enterprises being able to overwhelm those in small ones.

Another change carves out the building and construction industry from the multi-employer stream (although business says the definition of the industry is too narrow).

Despite the concessions, business groups remain angsty, saying they don’t go far enough. In a joint statement they maintained the planned expansion of multi-employer bargaining is too wide. (There is general support for it for low-paid industries such as aged care and child care.)

The peak business groups, which have united in pressing for changes, claim the legislation will undermine enterprise bargaining.

The battle over the bill has given a deeper insight into the Albanese government.

It has shown that while Labor presented as a small target at the election, it had a larger agenda in its back pocket.

Also, while Albanese wants a good relationship with business, this issue underscores the strength of Labor’s ties to the unions. On the other hand, to get something they want when they want it, the unions are having to live with the ground the government is giving to business. The unions claim these concessions will make the multi-employer bargaining harder (outside the low-paid stream); they also play down some changes to the bill that are being made for their benefit.

While there has been a lot of talk about how politics has altered under the new government, the toing and froing over the workplace legislation shows much remains the same, as stakeholders and those with Senate power seek to influence the outcome.

Pocock met Albanese on Wednesday. A feature of the early months of his prime ministership is that the PM prefers to stand above the fray, leaving the carriage of issues to his ministers. But he is putting his shoulder to this particular wheel.

Pocock is very aware of his own clout. When the two met over a cup of tea, the message from Pocock was clear: he wouldn’t be declaring a position on the bill until the Senate committee examining the legislation makes its report, due November 17.

Given the extent to which the government is willing to compromise, the odds would seem on the bill being passed before Christmas. Even though there is a strong case against haste, it would be a big deal for Pocock to hold up for an extended period what the government is casting as urgently-needed legislation.

But we are unlikely to see Burke and Pocock posing together on a parliamentary garden bench, as Reith and Kernot did.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra. This article is republished from The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply