Did Anthony Albanese realise what a rough journey this referendum would be, asks political columnist MICHELLE GRATTAN?

ANTHONY Albanese has invested heart, soul and political authority in his battle to change the Constitution to establish an indigenous Voice to parliament. His tears this week at Uluru, when surrounded and celebrated by Aboriginal women, showed a deep well of emotion.

If, as the polls indicate, the Voice is defeated on Saturday, it will be a devastating rebuff for the prime minister. He’ll have raised indigenous hopes only to see them dashed. He’ll have led Australians on an arduous journey only to have them desert him before the destination. Did Albanese realise how risky this bold constitutional gamble would be? Some colleagues will shake their heads at his judgement.

Whatever a defeat would do immediately to Labor’s rating, it wouldn’t necessarily have much effect in the longer term. The reason partly goes to why Albanese couldn’t persuade more people to vote “yes”.

For a large swathe of voters, the Voice is a second or third order issue. At the 2025 election, most voters will have first-order issues on their minds – their own economic circumstance, assessments of the government’s general competence, what they think of the Dutton alternative. The Voice will have receded into history.

Immediately, however, a loss would trigger bitterness and anger among many indigenous people, feeling they’ve been spurned by other Australians. Albanese will need – as a fallback – a plan to try to tackle indigenous disadvantage by another route.

This bruising referendum campaign has given insights about the various players and our society more generally.

If it’s shown that Albanese, mostly cautious as leader, has been willing to back himself to the point of overreach, it’s also reinforced Peter Dutton’s image as a hardball, Tony Abbott-style opposition leader.

Just as Abbott was brutally relentless in fighting Labor on climate change, so Dutton has been in prosecuting the “no” case. Negative politics fits Dutton like a glove, and he’s made the most of this opportunity, while losing some prominent Liberals to the “yes” campaign. He’ll receive a dose of immediate blame, and pay a price on the Liberals’ left flank, in teal seats the party needs to regain.

The referendum has highlighted what many have previously overlooked or denied: that indigenous Australians (like other Australians) aren’t of one political mind.

During the campaign, Albanese repeatedly said the Voice enjoys more than 80 per cent support among indigenous people. This was based on polling early in the year; a Resolve poll of 420 people reported in Nine newspapers this week put support at 59 per cent.

It’s unsurprising there are differing views. Indigenous politics is robust. Also, Australia’s “First Nations” include a multitude of nations, with some smaller nations concerned larger ones will dominate a Voice.

The Yindyamarra Nguluway research program at Charles Sturt University has involved yarns with 24 elders. The findings show elders divided on voting “yes”. The key issues include a lack of trust in the process of change. There is also some dismay the change process has been couched in the context of giving a Voice to parliament to nations that have never ceded sovereignty.

Although the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart is viewed as an important step forward many of these elders view it to be an elite invention. Nevertheless, the general view is that the Voice is a necessary gateway into a more detailed conversation about the future of Australian democracy.

Indigenous leaders have been on the front lines of the “yes” and “no” campaigns: Noel Pearson, Megan Davis (“yes”), Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Warren Mundine (“no”), Senator Lidia Thorpe (progressive “no”). They’re articulating different philosophies.

Labor senator Pat Dodson, dubbed the “father of reconciliation” for his work over decades, told the National Press Club this week: “This is the first time that we’ve had in the public space a clear division between Aboriginal leaders. […] That division is quite substantial. It’s not just a matter of opinion.

“It’s a division based on whether you understand our history, that this nation was colonised, Aboriginal people were forcibly subjugated, that they were denied the opportunity to have a say on how they were going to be impacted. Or whether you say it was all cosy and that we were picked up in a truck and taken into the Winter Wonderland and we lived there forever in some sort of rose garden.

“Now, the sad part about the debate is […] if the No camp campaign gets up, it’ll be a debate about assimilation and co-option. That’ll be where the debate in the future goes. And I don’t think we should be having that debate, because assimilation is a very toxic word to many Aboriginal people.”

Price denies her position is assimilationist but that’s certainly its flavour. She and some other “no” leaders argue the emphasis should be on need, not indigeneity; “yes” leaders emphasise indigeneity as well as need.

The referendum has been a case study in how, on such a polarising issue, racism and nastiness will quickly and inevitably break the surface of the “respectful debate” both sides have claimed they want.

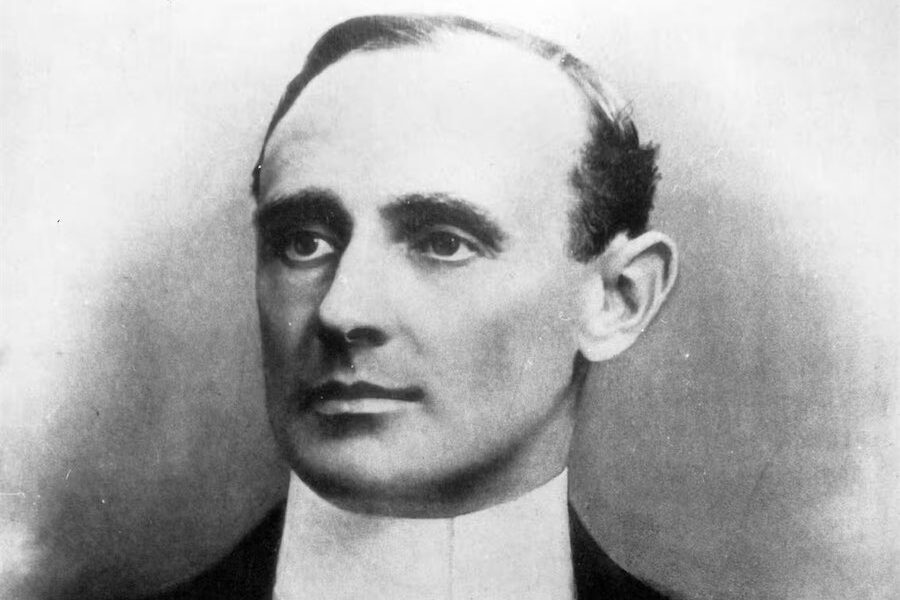

Social media and the nature of contemporary politics have undoubtedly debased this particular referendum. But it’s also an old story. Robert Menzies’ 1951 (unsuccessful) referendum to ban the Communist Party was vitriolic.

Anne Henderson’s recent book Menzies versus Evatt recounts how, when Menzies opened the “yes” campaign in Melbourne, then senator (later PM) John Gorton “wrestled with one interjector, allegedly snatching at the man’s collar and shouting. ‘Come outside, you yellow rat’. Police were reported as dragging the senator away rather than the interjector”.

At another meeting, when Menzies stood to speak, “an interjector shouted, ‘Heil Hitler’”. Menzies had a quick retort, “You call me Hitler and [opposition leader] Dr Evatt calls me Goebbels – make up your mind”. Propaganda came in pamphlet form rather than via the internet but it was just as gross.

In a democracy, sometimes giving people their say can mean enduring or dealing with a lot of bad behaviour.

After many weeks of people calling out some appalling examples of racism in the referendum, suddenly we see disturbing signs of ethnic hate flare in a totally different context – Hamas’ weekend atrocities and Israel’s retaliation.

The activities of neo-Nazis in Australia might be limited but they appear to have increased. ASIO has repeatedly warned about the growth of right-wing extremism. Even so, to hear chants of “Gas the Jews” at Monday’s Sydney pro-Palestinian rally was extraordinarily shocking.

ASIO head Mike Burgess warned in a Thursday statement: “It is important that all parties consider the implications for social cohesion when making public statements. […] Words matter. ASIO has seen direct connections between inflamed language and inflamed community tensions.”

We should not stop people expressing their views through demonstrations. We should, however, crack down on hate speech, whether it’s directed at those of the Jewish faith, indigenous people, or anyone else.

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra. This article is republished from The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply