From Hilde with Love, which will open the 2024 German Film Festival on May 7, is a movie about the Nazi era such as you may have never seen before.

Not a swastika in sight. No dramatic music. No goose-stepping, and no evil villains twitching moustaches. Just people going about their daily lives.

That goes for Hans and Hilde Coppi, (Johannes Hegemann and Liv Lisa Fries) young members of an anti-Nazi resistance group, and it goes for their interrogators and guards in the Gestapo, not least the frigid warden, Frau Kuhn.

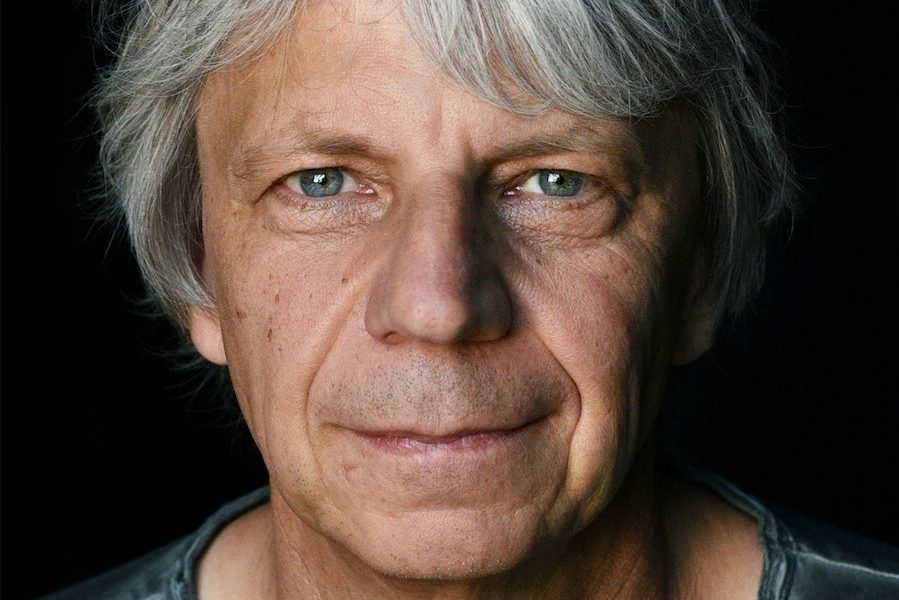

“It was very important not to show these as typical Nazi guys – powerful, strong and not friendly,” says director Andreas Dresen, one of German cinema’s leading lights.

Speaking by phone from Berlin, he tells me: “If you see them like that, it is very easy to stay at a distance.”

In the opening scene, as the heavily pregnant Hilde, an ordinary woman caught up in the resistance through her boyfriend/husband, is led into a Gestapo interrogation room, the Nazi lawyer puts a hand on her stomach to express his wonder at the miracle of birth.

As for Frau Kuhn (Lisa Wagner), Dresen tells me: “She goes through a kind of transformation, starting out being very powerful, but something in her head is growing.”

Everything about Hilde, now a national legend, is normal. She hasn’t been to university and she works as a dental nurse.

Dresen himself was born in the German Democratic Republic, and says, “In East Germany resistance fighters were kind of superstars and you could never compare yourself with them, but the reality is that they were actually quite normal people, having sex, enjoying themselves, going to work.”

But to West Germans they were traitors and it was only in 2009 that Germany officially exonerated them – “horrible,” he says.

“Hilde is to me an ordinary working-class person. You wouldn’t call her a heroic resistance fighter. She’s just in the middle of it, although when she went into prison, she became braver, maybe because she had become a mother and she had to defend her child.”

All “typical Berliners”, Dresen says, the young people in the film enjoy cycling on weekends around the beautiful lake-dotted flat landscape surrounding Berlin-Brandenburg, skinny-dipping, dancing, drinking and lovemaking, while in between trying to send telegraphic messages of hope to comrades in prison on the Soviet side.

They all get caught and the results are inevitable.

There’s no black-and-white. In the first interrogation scene, the lawyer offers Hilde a liverwurst sandwich while even the brutal interrogator can crack a joke.

“These are just ordinary people going about their business” and even Hilde is no shining heroine, Dresen tells me. “She just has to do what she has to do.”

Cleverly interspersing interrogation and incarceration scenes with joyous scenes of youthful abandon, this is a film for those who want to understand what Brecht called “the private lives of the Master Race”, with no sentimentality.

The research is extraordinary. Dresen says that they weren’t 100 per cent faithful to history, but they come pretty close to it and were able to film in some of the real-life locations.

In one scene, in the apartment of Libs, a wealthy member of the so-called Red Orchestra group, there is real Bauhaus furniture.

Some scenes, like the executions, run at breakneck speed, reflecting the Nazis’ real-life protocols where they noted the times until the very moment of death.

But Dresen is more famous for his ability to slow down a scene where needed.

In the searing scene where Hilda gives birth to her baby, Hans, in the prison hospital. Instead of skimming over the horrors of a birth scene going wrong as most directors would have done, he focuses on every detail, so that you feel as if you too are giving birth.

“The important thing for me, as a director, is not to have people look away,” he says.

That slow approach is also used in the film’s exquisite sex scenes between Hans and Hilde.

Dresen believes that he and his team succeeded in recreating the feeling of the real-life events in 1942. The real-life baby, Hans Coppi Jnr, now 81, was able to view the movie in a private screening and later to the applause of 2000 people at its premiere.

“There was a bit of a feeling that this was kind of late justice for his parents,” Dresen says in understatement.

Ironically, we learn at the end that the resistance group Hilde belonged to was ineffectual, so that only one of their messages ever got through to the other side.

“We knew this, because we had done the research, but we wanted to make the point that whether resistance fails or not doesn’t matter. It’s of vital importance to resist terror regimes,” Dresen says. “Everybody has to think about it.”

2024 German Film Festival, Palace Electric Cinemas, May 7-29.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply