Packed off with clothing, a prayer book and a hairbrush, Anne and Alicia Keefe were two of more than 4100 Irish women to arrive in Australia between 1848 and 1850. Yesterdays columnist NICHOLE OVERALL looks a local link with Ireland’s ‘Potato Orphans’.

THE waifish Irish girls were judged fit for purpose: aged between 14 and 20, single – and free of any infectious disease.

On July 25, 170 years ago, Anne and Alicia Keefe, wearing the blue shifts that marked them as Earl Grey Orphans, boarded an English transport ship bound for the other side of the world.

They were escaping an Ireland riven by famine and destitution.

Packed off with some clothing, a prayer book and a hairbrush, Anne and Alicia were two of more than 4100 of their countrywomen – girls, really – to arrive in Australia between 1848 and 1850.

While the parent-less teenagers weren’t convicts, the colonial outpost was bursting with men who once were (as well as others still serving at Her Majesty’s Pleasure). In short supply were domestic servants and marriage prospects.

The initiative of Earl Henry George Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, sought to relieve the “misery, poverty and in likelihood, early death” that came in the wake of the “Great Hunger”. In addition, it would address this gender imbalance.

The destiny of the Keefe sisters was to be among a select few to put down roots in what would become the capital region – where some of their descendants continue to live today.

Robyn Sherd McVey, formerly of Canberra and now tiny Ungarie (central west NSW), is Alicia’s great-granddaughter.

“I’m quite obsessed in relation to all aspects of my courageous, pioneering ancestors,” she says.

“It was through searching for information on Alicia I discovered she was an ‘Orphan’. What I hadn’t realised until now was how young she may have been.”

The records on this are conflicting. The shipping register states Anne was 16 and her sibling (also listed as Alice) 15, but official certificates indicate Alicia was only 11. Given the minimum-age requirement, Alicia’s was perhaps altered to ensure the pair wouldn’t be separated.

Almost on the anniversary of their departure, a play on the short-lived “Potato Orphans” scheme is to open at The Q in Queanbeyan on August 24.

“Belfast Girls” focuses on five such women during their months-long journey. Set in the third-class confines of a crowded ship, it explores the impetus and potential for transformation. With bonds forged through shared experience, pasts are revealed, and expectations and hopes for the future are laid bare.

According to playwright Jaki McCarrick, it was always intended as an allegory, its central quintet an amalgam and embodiment of the thousands of stories. The title is a reference to those less inclined to fulfil another of the stipulations: “obedient”.

“At the time of writing, I think I was more angry at how the populace – and women in particular – were treated during the famine,” Jaki says.

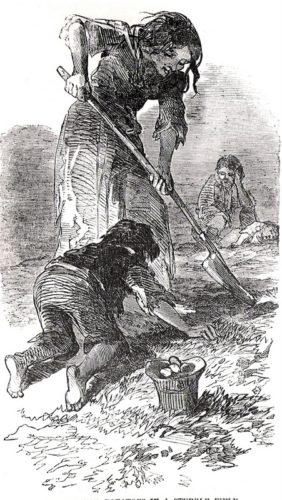

In 1849, the Emerald Isle was far from the sparkling jewel its poetic appellation suggested. After three years being ravaged by the Great Famine, brought on by a potato blight, a million or more of its citizens were dead.

Workhouses built to cater to the starving and the wretched were overcrowded, disease-ridden and devoid of promise. The alternative was a life of crime or prostitution.

While emigration may have precluded such fates, it wasn’t always a step up.

Anti-Irish/Catholic sentiment was strong among an aspirational population trying to shake itself of its criminal origins. The local press declared the arrivals “workhouse sweepings”, and worse, “hordes of useless trollops, thrust upon an unwilling community.”

As a result, a goodly proportion allowed themselves and their stories to be swallowed up in the unexplored wilds of this isolated new world. Others sought to reinvent themselves.

Anne and Alicia, plucked from a “hated” institution in Queen’s County, arrived on November 21, 1849 (less than nine months later the controversial program would end). They gained employment relatively close to each other; Anne near Crookwell, Alicia at Goulburn.

Less is known about Anne’s story, save that she married Thomas Murphy, of Bungendore, in 1851. Her great-niece, Robyn, is of the belief that their progeny were numerous and that many of the family wound up in Braidwood and Moruya.

In 1859, the first of seven children was born to Alicia and William Sherd, a Bungendore “confectioner”.

“When William left England [c1853], he left his wife and two sons,” says Robyn.

“I’m a novice with genealogy but suspect that Alicia and William may have been in a common-law relationship.”

Today theirs is a well-recognised name throughout the area, with Bungendore’s main sports ground named for one of Alicia and William’s great grandsons, Mick Sherd.

On Alicia’s death in 1896 in the Queanbeyan Hospital, she was buried in an unmarked grave in Bungendore’s cemetery.

A third local Orphan has also been unearthed: Mary Ann Duddy. As a 16-year-old from Galway, she was sent out in early 1849. The following year, she married Robert Sindel, 23, settling in Queanbeyan in 1859.

Although illiterate (unlike the Keefes), Mary Ann helped run her husband’s general store, Manchester House. And she gave birth to 11 children. When she died – on the premises – she was just 37.

Mary Ann appears on the Welcome Wall of the Maritime Museum, erected in honour of all who’ve made Australia home.

Another memorial, the Irish Famine Monument at Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney – the initial residence of the Orphans – marks its 20th anniversary on August 25.

Its glass panels are etched with 420 individuals representing all those so displaced.

“I attended the Famine Commemoration at Hyde Park last year with three of my siblings and it was wonderful to see Alicia noted there,” says Robyn.

According to its artists, “as their names fade on the glass so does the memory of some of these young female immigrants.”

Works such as “Belfast Girls” and those keen to preserve the identities and contributions of their forebears are ensuring they will never truly fade.

Do you know of any local Earl Grey Orphans? Visit anoverallview.wixsite.com/blog.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply