We’ve been here before, just over a century ago when the Spanish Flu swept across Australia. Infecting 40 per cent of the country, it brought bans on public events, quarantine and the mandatory use of face masks, writes “Yesterdays” columnist NICHOLE OVERALL.

“ALL persons travelling from infected areas [are] asked to submit themselves to an inhalation chamber”.

Masks normally the domain of health professionals are donned by the public and proclamations issued on everything from travel restrictions to school closures and the cancellation of public events.

Communities disrupted, social cohesion fragmented, economies impacted. Whispers of the end of the known world.

No, not COVID19, but the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 (Spanish Flu). When it made landfall in Australia 101 years ago, while government-decreed precautions and restrictions provided challenges to day-to-day life, they largely worked. Along with being one of the last places on earth for it to arrive, the continent would also boast one of the lowest mortality rates.

That’s not to suggest misinformation and ill-informed debate weren’t rife. Today we’re witnessing the stockpiling of ‘loo paper and body-sized bags of rice; back then it was wearing red wrist bands, the colour believed to ward it off, and taking laxatives to “flush” out the system.

The previously unseen disease worked its way around the globe (the two qualifications of a pandemic) primarily through the survivors of a devastating war.

It was late January, 1919, before the flu was officially acknowledged as having breached the believed protected shores of Australia. The still new nation of a mere five million, closed its borders from October, 1918, on news the flu had made its presence known in NZ. Ships flying the yellow flag of contagion were held at bay, though with cases attended to at Fremantle and Manly’s Quarantine Station.

Within three months, the illness erroneously named for the Spanish on whom it had wreaked considerable havoc, had descended on the Canberra region. The not yet six-year-old national capital may have felt the direct consequences less thanks to its relative geographic isolation 300 kilometres from Sydney and more than double that to Melbourne – and its lack of population, but the ripple effect was wide.

The inhalation chamber as a precautionary measure was put forward at an Influenza Committee meeting in Queanbeyan on April 4, 1919. Dr Patrick Blackall, government medical officer, also outlined procedures for inoculation (a hurried concoction that was essentially useless), “arrangement for the relief of those who may be attacked by the disease”, and his efforts to source hospital equipment and masks, suggesting that “the Red Cross ladies might take up the matter of making and disposing of masks”.

This followed an initially lukewarm reception by the leading local news source, the long-running “Queanbeyan Age” (1860), to perceived “overly strict” preventative efforts.

In February, the paper pontificated that “the unforced conclusion is that the epidemic which caused so much havoc has spent its force, and that the worst Australia has to face is the continuance of an influenza which it has been familiar with for years”.

This appeared alongside an advertisement for free inoculations along with Queanbeyan, depots at Oaks Estate, the Canberra Hospital, Hall, Majura Recreation Hall, Tuggeranong School and Tharwa.

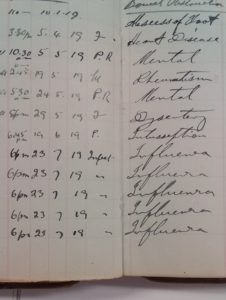

Towards the end of March, “rumours of a case of pneumonic influenza in Queanbeyan” were reported as “absolutely false”. However, there’d been at least one death in the Queanbeyan Hospital as early as January 13. Marion Dunlop, 45, of Bungendore, was recorded as having died of “double pneumonia”: what wasn’t recognised at that early stage was that “pneumonienza” paved the way for such secondary infections.

Goulburn recorded its first official victims on April 17. Forty-two of its residents would eventually be officially recorded as succumbing, including the city’s health inspector, JR Biddle. Nonetheless, “The Queanbeyan Age” remained unconvinced as late as mid-June.

“The present weather conditions are responsible for an epidemic of colds and catarrhal infections; but fortunately so far there has been no symptom of pneumonic influenza in the neighbourhood of Queanbeyan”.

Mere weeks later, the editorial tone was vastly changed. Page two pronounced that influenza was “now raging” in the town and the Public Health Department had been twice telegrammed with the request for another four nurses and an additional doctor to cope.

Elsewhere around the region, Michelago intended on using its School of Arts building as an emergency hospital, there were recorded instances in Yass, Bungendore and Braidwood, and multiple deaths in Cooma – seven within 48 hours, four of whom were siblings.

At the on-again-off-again, five-year-old “temporary structure” that was the Canberra Hospital at Acton (now, the ANU), half of its eight beds were occupied by infected patients. Returning servicemen were quarantined for 10 days there in specially erected isolation tents. Others were apparently “being treated in their own homes”. Some ignored the requirements entirely.

Part of the problem was the frequently changing arrangements. Restrictions were prematurely relaxed whenever cases seemed to ebb, but the peak wouldn’t occur until July.

Understandably, most were weary of war deprivations, rationing and bad news and the expectations offered little joy: in the same year the Royal Easter Show in Sydney was cancelled, so too, the Queanbeyan Show.

By year’s end, it’s estimated 40 per cent of the country had been infected, with as many as 15,000 dead. Of course, the true figures can never be known. How much worse though, might it have been?

While some of the early editorial content put forward by “The Queanbeyan Age” was contrary to the wider public good, the advice became more sensible – and in our current environment, bears repeating.

“We can refuse to be ‘stampeded’ by unworthy panic and summon to our aid that courage which is equally heroic in endurance as in action… Is it not true, at all times and in all places, that panic is more dangerous than the circumstances which apparently produce it?”.

Alternatively, if we’re going to insist on hoarding toilet paper, might as well make use of it and give those laxatives a try.

For more on the local experience, anoverallview.wixsite.com/blog

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![Canberra’s woodchopping association – the Hall and District Axemen’s Club – is rebranding to Capital Country Woodchopping.

“We didn’t want to be exclusively a Canberra association and we deliberately left any gender-specific wording out in the new name,” says president Cheyanne Girvan, 32.

“We also went a different [way] to other associations under NSW by not including ‘association’ in our name.”

Four years ago the Hall and District Axemen’s club’s membership was 25.

Cheyanne says this name change will give the club the versatility to grow into other areas and on to greater things.

To read on about Cheyanne's story with the woodchoppers, visit our website at citynews.com.au or click the link in our bio!

@@capitalcountrywoodchopping

#woodchopping #woodchoppinggirl #woodchoppingaustralia #axemen #axewomen #woodcutter #canberrastories #storiesthatmatter #citynews #journalism](https://citynews.com.au/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)

Leave a Reply