“Yesterdays” columnist NICHOLE OVERALL reveals the story and mystery of Christ Church Queanbeyan, which opened to the district’s Anglican faithful on October 7, 1860.

RUN your hands along its chiselled, tawny-hued stone walls and it’s almost possible to feel the past that lingers within the Victorian Gothic church after 16 decades catering to the stuff of life.

Births, deaths and marriages, Sunday worship and milestones – the manifestation of the evolution of a community, a town, a region – over 160 years, filling countless volumes devoted to such records.

As one of the Canberra area’s longest surviving ecclesiastical constructions, there’s also the curiosities, quirks and even a mystery or two for good measure.

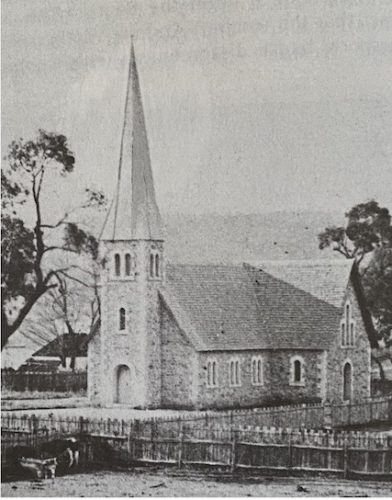

Initially without its 75-foot spire and the stained glass windows to the memory of many a prominent local citizen, Christ Church opened in service of the Queanbeyan district’s Anglican faithful on October 7, 1860.

A year later, on October 30, the second Bishop of Sydney, Frederic Barker, conferred consecration – that is, performed the highly specific ceremony intended to deliver it from any evil.

Sheltered within stately grounds set upon the bank of a picturesque river, Christ Church remains as impressive as when it first appeared for a host of reasons, not least its prime real estate.

A pin to mark the close to 1.2-hectare (three-acre) site on a map shows it to be virtually the geographic heart of the once tiny “village” that’s grown into a major regional centre around it.

In a modern setting, it’s noted as representing “a consolidation of the city centre and of the Anglican faith in the region; this National Trust classified precinct is one of Queanbeyan’s most historically significant sites”.

The building was the second house of God to then stand upon the Limestone Plains – the other, the similarly-styled St John’s in now Canberra, completed mid-1844.

It was though, the third to exist: Christ Church Mk 1 was a simple edifice of “rubble-stone walls, without buttresses”, erected in time for Christmas, 1844 – and hence its name.

Its boast was to outdo merchant Robert Campbell’s St John’s, constructed nearby his estate, Duntroon (1833), for the approved status of consecration. No less than the Bishop of Australia of the Church of England, William Broughton, would perform the ritual for Christ Church on March 8, 1845. The Scottish Campbell’s “kirk” would wait another four days.

The Queanbeyan church grounds were designated on the small grid of streets etched to indicate the original 1838 plan for a town. Six years later they’d also be home to the wider area’s first educational establishment (followed by Ginninderra and St John’s school).

The quaint inaugural schoolhouse – just a single room with a dirt floor and accommodating as many as 30 pupils at once – still stands on the southern boundary of the land parcel given up for holy purposes.

Added at the same juncture were a rudimentary parsonage and rough-hewn, whitewashed stables. The home of the horses, vital to an early parson given the extraordinary area for which he was responsible, also survived.

Not so fortunate, the “old” church. At a humble 44 feet by 24 feet, it was deemed no longer an edifying enough testament to God in his heavens.

Enter the 30-year-old reverend Alberto Dias Soares, son of a Portuguese knight, who’d trained as an artist and engineer in Paris.

While not formally trained as an architect, his own church would become one of 30-odd for which he’d be acknowledged, from Burra to Bungendore and beyond.

Christ Church would be remade seemingly in the likeness of St John’s with a “cross-shaped plan form” crafted by the Irish-born local builder Daniel Jordan.

Having added to the school in the mid-1860s, a decade later Soares decided a two-storey rectory was necessary, rising closer to the river in local, high-quality, hand-made red brick.

Of the more unusual characteristics of the locale, one is the absence of a graveyard.

While it was declared that St John’s adjacent burial ground “was to be the resting place of all Christians”, it took some time to access in those earlier days, never mind having to cart along a body as well.

Given that until 1846 Queanbeyan only had an unconsecrated area in Oaks Estate – where there’s still said to be up to 44 bodies buried in unmarked graves – the lack of such a nearby opportunity remains surprising.

Today when coffins make their final journey from Christ Church, they pass beneath the “lych” gate at the main entrance, redesigned in 1947 as a memorial to parishioners who lost their lives in two world wars.

Like something out of a Jane Austen novel, they’re traditionally found in English churches at the end of what were known as “corpse roads”, along which bodies were carried for burial. A superstition attached to them is the belief the spirit of the last person buried in proximity remains to guard over, earning their title of “Resurrection Gates”.

There have been tragedies within the grounds themselves, including the sad coincidence that both of the first ministers, Edward Smith and Soares, had infants who passed away in the old parsonage.

Just beyond where that building stood, off to the side of the main drive that encircles the church, there’s a pair of faded, rust-riddled, wrought-iron gates.

Flanked by two sturdy timber posts, they’re firmly secured with a heavy, weathered chain and padlock – despite the fact that they stand attached to nothing, keeping neither anything in, nor out.

These were those that were front and centre from 1884.

Now, literally, Gates to Nowhere. Or perhaps it’s the past they open to us, a rich and fascinating view down a lane of memory to a time when an unassuming structure with a panoramic view of a pretty watercourse nestled in a valley protected by surrounding outcrops arose to serve both the community and the Lord.

More of the history and the mystery here.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply