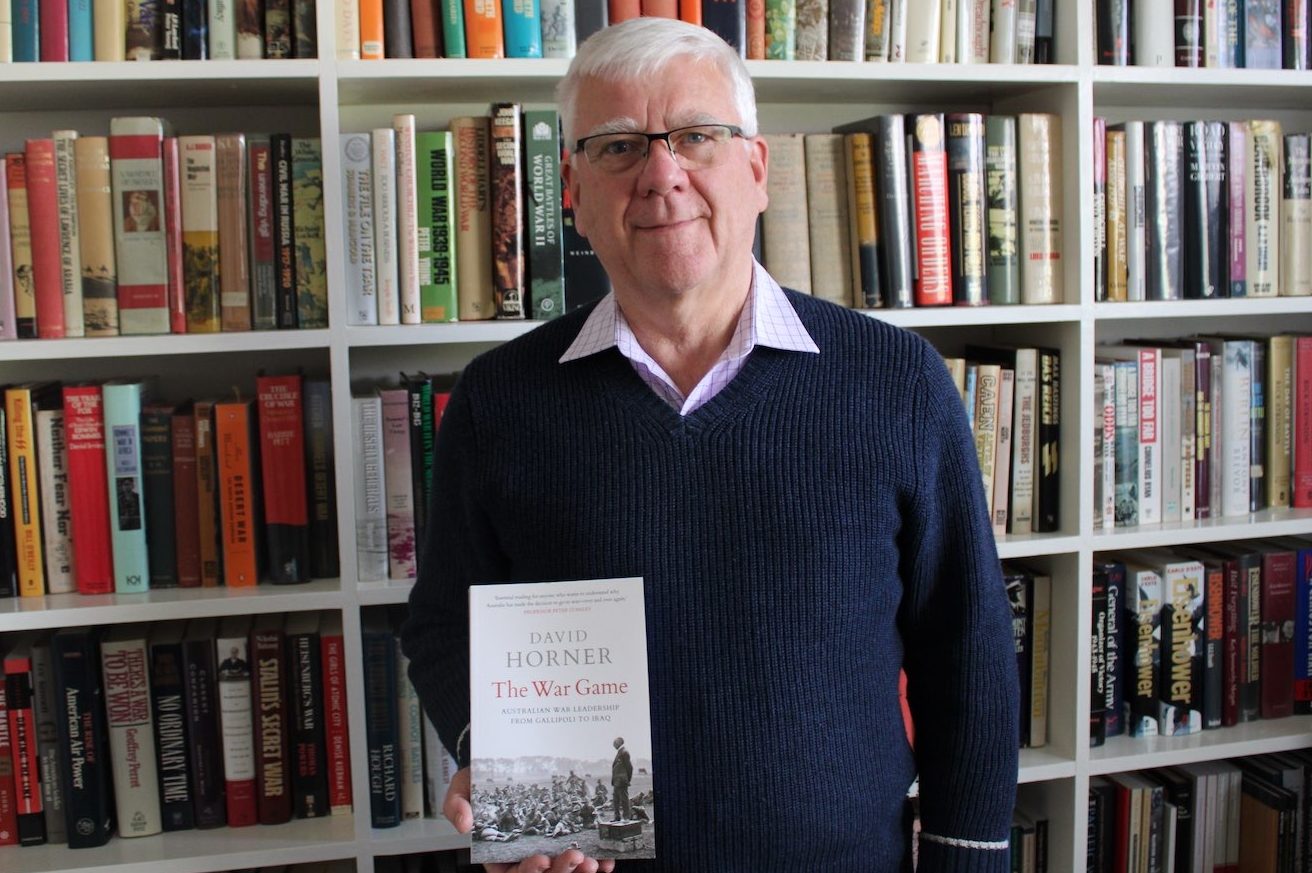

THE gravest decision a leader can make is to send their nation to war, says ANU professor of Australian defence history David Horner.

Considered the country’s pre-eminent military historian, he would be the first to tell you the bravery of Australian soldiers in battles such as Gallipoli or on the Kokoda Trail should be deeply respected.

But in his newest work, “The War Game”, he raises what he believes to be an even more important point: should they have been there in the first place?

Prof Horner, who himself served in Vietnam, has investigated the nine times that Australian leaders have sent the nation to war over the last century and the political mechanisms by which those decisions were made.

From Prime Minister Joseph Cook’s committing Australia to World War I, to John Howard’s call to intervene in Iraq, Horner’s book asks the questions of why these decisions were made, how informed they were and what can be learnt from them today.

“These decisions result in the death of Australians, they result in the grief of families, they result in the effect on the Australian reputation and the treasury,” he says.

“These are issues that we’ve been dealing with for 100 years and these issues are enduring. The situations are different but the broad lessons are there.

“With the war in Ukraine and the concern about China, the sorts of issues I’m talking about in the book are more important than they’ve been for decades.”

In the book’s introduction, Prof Horner uses a letter written by US President Abraham Lincoln to Union Army Gen Ulysses Grant as a springboard to examine what he calls the “political military interface”.

Lincoln wrote to Grant during the American Civil War: “The particulars of your plans I neither know nor seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant, and pleased with this I wish not to intrude any constraints or restraints upon you. If there is anything wanting which is in my power to give, do not fail to let me know it.”

Prof Horner says: “The question comes, how far down should the government get involved with the actual conduct of the military operations?”

“Some would argue that Mr Lincoln’s model is not good enough, that he should interfere more than that it would seem to suggest.

“Others would ask: why should the leader or minister for defence interfere, and if they do, how low down should their decisions go?”

While the US Civil War may have taken place more than 150 years ago and an ocean away, Prof Horner says those same questions around the interplay between politics and military remain for Australia today.

“We’ve never had a prime minister who has a particular expertise in international strategic affairs at the time they were elected, but the effects of their decisions go on for years,” he says.

“We see now with the decision to go to Afghanistan and the way the war was conducted has resulted in continuing problems with PTSD, Australia’s reputation and so on.

“We have to ask the question, if we’ve got prime ministers who are making these decisions, how capable are they to make them?”

In his book, Prof Horner points to a quote by former UK Prime Minister David Lloyd George who raised similar questions more than a century ago:

“In all trades and professions the man who aims at taking the lead knows that he must first learn the business he proposes to follow, only in the business of war – the most difficult of all – is no special training or study demanded from those charged with, and paid for, its management.”

In light of such issues, Prof Horner posits that the country’s top military officials should have greater responsibility in military decision making.

“The failure of the US in Iraq should lead to at least two vital conclusions: that the US process for going to war was deeply flawed and Australia would be wise to treat any US plan for war with deep suspicion,” he says.

He says that despite the situations of war changing over the course of 100 years, the broad lessons from history remain just as, if not more, important for Australia’s leadership today.

“Just as a game has rules, there are rules for effectively playing the war- leadership game.

“And if we’re getting ourselves involved in another war, let’s stop and think: are we making a mistake?”

“The War Game: Australian War Leadership from Gallipoli to Iraq” is available at bookstores and online.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![Canberra’s woodchopping association – the Hall and District Axemen’s Club – is rebranding to Capital Country Woodchopping.

“We didn’t want to be exclusively a Canberra association and we deliberately left any gender-specific wording out in the new name,” says president Cheyanne Girvan, 32.

“We also went a different [way] to other associations under NSW by not including ‘association’ in our name.”

Four years ago the Hall and District Axemen’s club’s membership was 25.

Cheyanne says this name change will give the club the versatility to grow into other areas and on to greater things.

To read on about Cheyanne's story with the woodchoppers, visit our website at citynews.com.au or click the link in our bio!

@@capitalcountrywoodchopping

#woodchopping #woodchoppinggirl #woodchoppingaustralia #axemen #axewomen #woodcutter #canberrastories #storiesthatmatter #citynews #journalism](https://citynews.com.au/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)

Leave a Reply