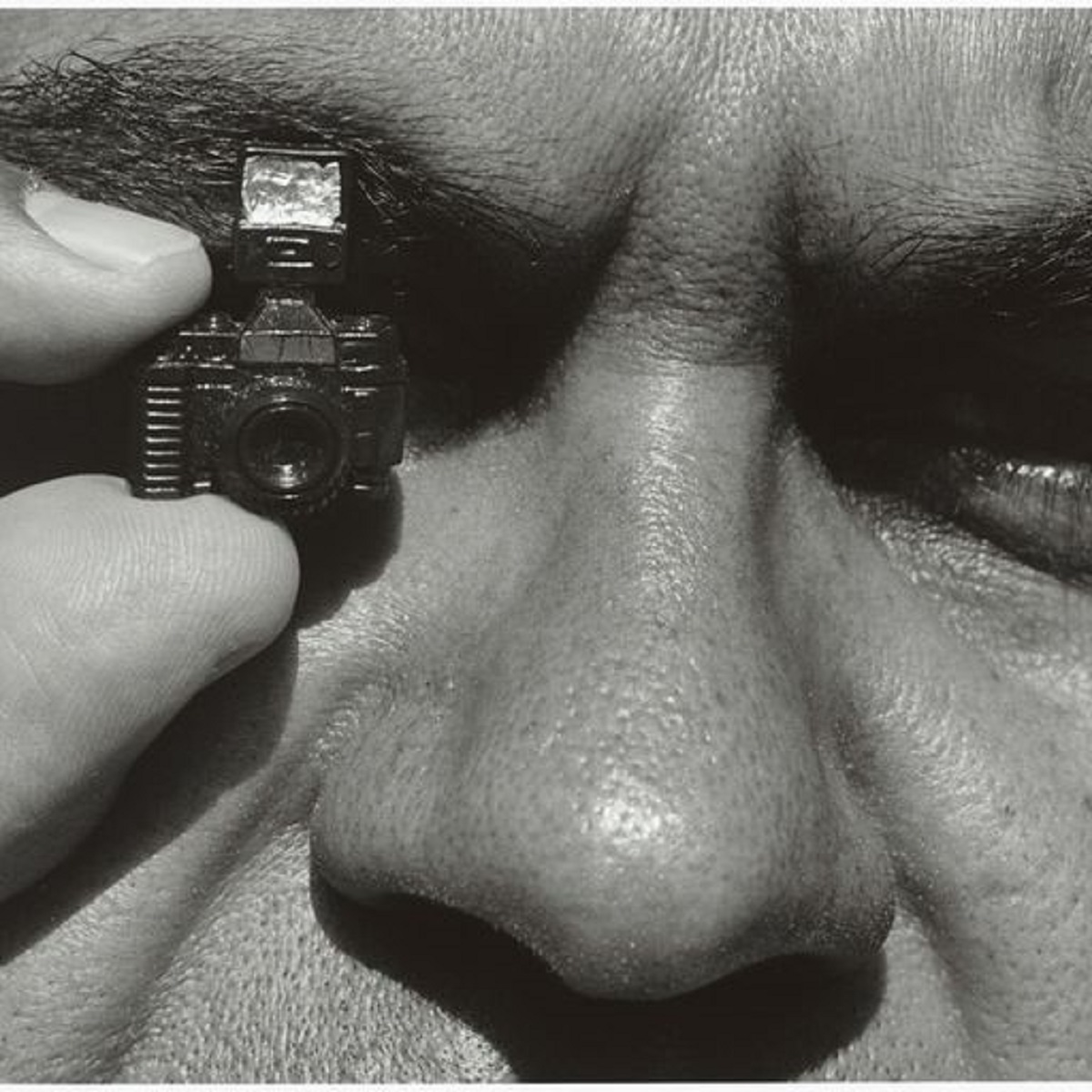

“Self Portrait” by Mervyn Bishop.

Photography / “Viewfinder – Photography from the 1970s to Now”. At the National Library until March 13. Reviewed by CON BOEKEL.

THE accession aim for the National Library’s collection of digital images is to document Australian life.

This exhibition’s 120 selected prints are grouped by themes: “people”, “work”, “play”, “natural environment”, “built environment” and “events large and small”. Most of the images are by established photographers.

The terms “to document” and “Australian life” beg endless questions. The solid backbone of the exhibition consists of images of ordinary Australians going about their ordinary lives. There are highlights and significant gaps. Most images document Australian lives at face value. Others challenge the status quo.

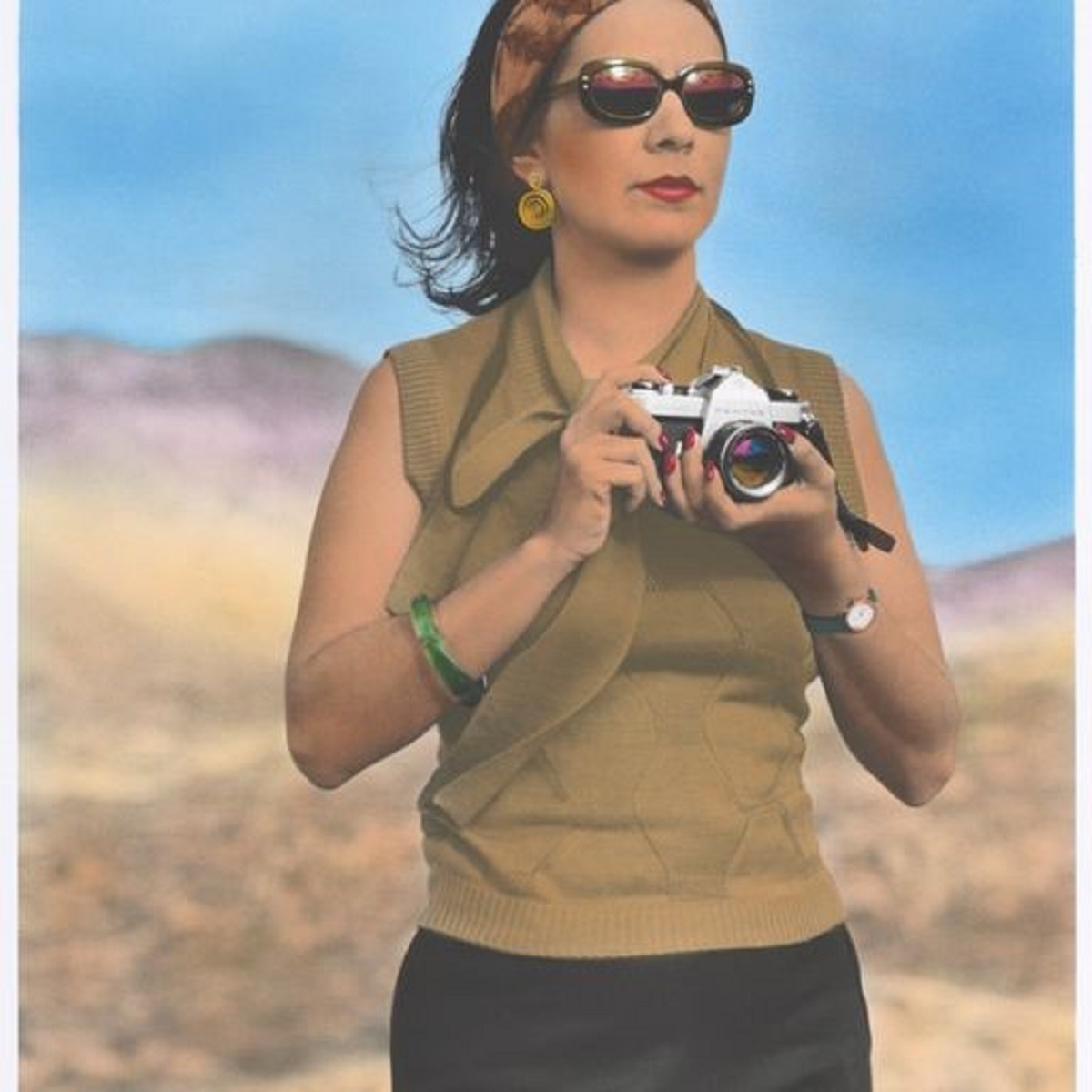

Among the latter, images by Tracey Moffat and Mervyn Bishop stand out. Moffat empowers herself by presenting herself as the photographer. The juxtaposition of a camera-carrying, modern, indigenous, urban woman wearing modish sunnies in a vaguely arid landscape is a command-and-control performance.

Bishop adds whimsy by using a tiny camera. These images are documentary points in a much broader and deeper movement by indigenous peoples to seize control of their individual and group destinies. Other minorities have also sought to reframe photography. Anna Zahalka pictures a burkini-clad Ozzie Mossie holding a surfboard on Cronulla Beach. This is a direct riposte to the shock-jock schlock that fostered the Cronulla riots.

Other images document aspects of Australia which are long gone. These include Ruth Maddison’s machinery operator in a spinning mill and Andrew Chapman’s engine fitter in a vehicle manufacturing plant.

Some images generate considerable beneath-the-surface psychological power. Martin Mischulnig’s image of an isolated motel sign, combined pictorially with a closed service station in an enveloping darkness, hints at the tyranny of distance and the desolate loneliness of our long distance road trips.

The “natural environment” section demonstrates a deep curation conundrum: whether or not to select “natural” environmental images with or without people in them. The majority of the choices in this section are people-free.

How might photography best represent the causal relationships between Australians and nature? The exhibition’s images of flood (Bruce Postie), fire (Matthew Abbott, Simon O’Dwyer), suburbanisation (Mischkulnig) and salinisation (Bill Bachman) carry part of this documentary load.

On the other hand, the supposedly “natural” look of the Cradle Mountain image by Peter Dombrovkis misdirects. It is stunningly beautiful. But the vegetation around Cradle Mountain is being altered by climate-change fires. Indigenous people are not extinct in Tasmania. And where are the hundreds of thousands of Cradle Mountain tourists?

This number of images cannot hope to cover the whole of Australian life but there are big gaps. Even though we have been at war for nearly half of the past 50 years there are no military images. Health and education settings are absent. More obliquely, surely 26 million Australians spend some time in bed?

The “documentary” outputs of fake image generators, of mass surveillance cameras and of the tsunami of selfies are largely absent from the exhibition. Yet these outputs are already reframing how we document ourselves.

Choosing 120 images from one million images was a monumental and perhaps even a nightmarish task. To his credit, Matthew Jones has curated a thought-provoking and entertaining outcome.

This major national photography exhibition is a must. You will see echoes of yourself, the people around you, your lived experiences and the places in which you live, work and play.

Shining through, the photographs are some of the best of the best.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply