Frank and Sylvia Manley were out for a spin in their new silvery-green HQ Monaro coupe. Driving across the 1025-metre, four-lane Tasman Bridge was to be a moment forever frozen in time, writes Yesterdays columnist NICHOLE OVERALL.

The real-time footage from the Port of Baltimore on that dark March night still arouses disbelief.

The cargo ship, the length of three football fields and laden with containers, careens into the steel-truss bridge; within seconds the 2.6-kilometre structure folds in upon itself as if made of matchsticks.

The lives of six road workers were lost and the stricken leviathan has only just been freed from beneath the twisted wreckage, seeing the shipping hub fully reopened.

With the American city’s skyline and psyche irrevocably altered, for me the surreal catastrophe conjured two Australian tragedies of similar proportions.

In the case of the second, the Cooma Car Museum was the setting for my meeting with a survivor who defied death in the most incredible of circumstances.

In 2022, the lively then 92-year-old Frank Manley was the guest of honour for a dinner as the 50th anniversary of his ordeal approached.

The first instance had occurred on October 15, 1970. In the midst of being built, a huge portion of Melbourne’s West Gate Bridge collapsed.

The more than 100-metre span weighing 2000 tonnes plunged 50 metres into the Yarra River, “the roar of the impact, the explosion, and the fire that followed… clearly heard over 20-kilometres away”.

Attributed to construction and engineering failures, 35 workers were killed, 18 seriously injured. It remains Australia’s worst industrial accident.

The other shocking event occurred in Tasmania almost five years later.

Hobart’s Derwent River on Sunday, January 5, 1975, just before 9.30pm was fog-bound for a height-of-summer evening.

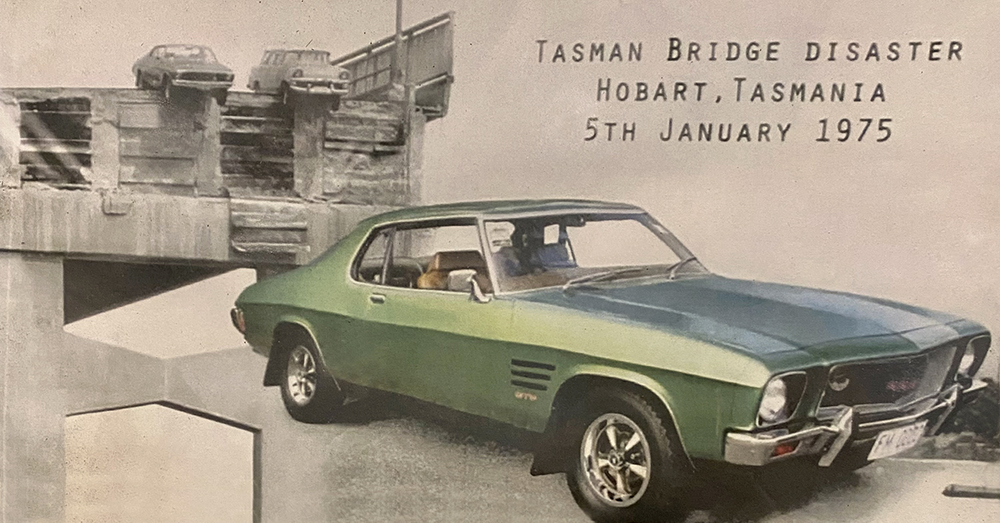

Frank and Sylvia Manley were out for a spin with two family members in their new silvery-green HQ Monaro coupe – unbeknown to many, the car named after the Monaro region.

Driving across the 3363-foot (1025-metre) four-lane Tasman Bridge, it was to be a moment forever frozen in time.

Without warning, a terrified Sylvia began to squeal.

“The white line! The white line’s gone! Stop!”

“I can’t, I can’t stop,” Frank hollered back, standing on the brakes.

Mere metres ahead, the road had vanished into the gloom before their astonished eyes. Two other cars in front had been swallowed up by the pitch-black chasm.

The bonnet of the Manley’s muscle car skidded over the gaping void. Then, unbelievably, forward motion ceased and they were seemingly suspended in thin air.

Sylvia later said that below they could see “a big whirlpool of water” and a “boat” sinking fast.

In Frank’s re-telling, flinging doors open, they clutched the headrests, pivoting backwards to scramble on to the roadway.

As they sought to distance themselves, a petrified Frank looked behind to see what had saved them.

Little more than the skin of the Monaro’s two back wheels was clinging to the surface of what was left, the transmission on the car’s underbelly holding it in place.

Precariously perched alongside was another Holden, a station wagon. It had contained the Lings: Murray, wife Helen and their two children. Having managed a screeching stop, a car behind had nudged the wagon’s front wheels over the edge.

Safely extracting his family, Murray could only watch in horror as two other vehicles ignored his frantic gesturing to pull up, the occupants plunging to their deaths.

Constructed 10 years earlier, the graceful bridge featured a high-level shipping navigation span.

However, the ill-fated, more than 11,000-tonne bulk carrier Lake Illawarra, lost control, colliding with two central pylons.

Some 400 feet (127 metres) of concrete buckled and plummeted 150-feet (45 metres), crashing down upon the ship’s bow as it did.

The vessel sank within minutes. Seven trapped crew were drowned. Five people died in the four cars that disappeared into the abyss. One victim was never recovered, only officially declared dead by a coroner in 2015.

As with the Baltimore tragedy, the timing meant there were fewer deaths than would otherwise have been the case.

It would take almost three years for the bridge to be rebuilt. Memorials were later erected and the MV Lake Illawarra lies undisturbed in 34 metres of water on the Tasman Bridge’s southern side.

Almost too fantastic to believe, this disaster was captured in an iconic photograph.

Cooma’s impressive, volunteer-run car museum boasts a copy alongside a photo of Frank Manley’s famous, locally-linked car.

Frank still regales all who want to hear with his memories of the extraordinary event, which remain as intact as the beloved HQ Monaro he still proudly owns – on display at the National Automobile Museum of Tasmania.

As Frank told it: how could you let go of something that hadn’t let go of you?

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply