A man on the back of a truck cuts open a hessian sack and plunges his hand in, taking out a clump of loose, grey, fibrous material; dropping it into the beating metal blades of a hopper attached to a fan.

In the roof cavity of a nearby home, another man holds a hose leading from the truck, directing a stream of the now fluffed up material across the surface of the void, creating a thick blanket that will weigh almost 120 kilograms.

The dust permeates the air and like his colleague on the truck, he wears a mask to avoid the unpleasant irritation it causes. The mask offers little protection; the inside of it coated with the grey fibres. Neither the men, nor presumably the owners of the home, realise the danger they’re in, or the lasting legacy this material will have.

Observing the men are two senior officials from the ACT Health Services Branch of the Commonwealth Health Department, accompanied by a scientist named Gersh Major who is concerned by what he sees. It was July 1968.

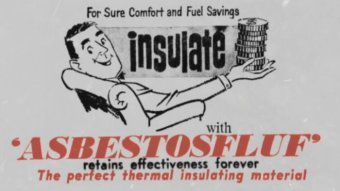

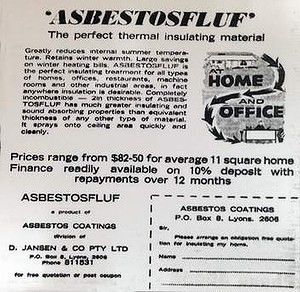

Earlier that year, an entrepreneur named Dirk Jansen launched Asbestosfluf, an insulation product he marketed to home and business owners as safe, affordable and long lasting. He went so far as to claim the CSIRO had approved it. It was in fact pure amphibole asbestos. Concerns quickly arose about Jansen’s venture, prompting the Health Department to investigate. It was at this early stage that a dangerous and expensive five-decade legacy could have been avoided.

Obtained in March this year, a report prepared for the Department by Major warned that the installers were being “unnecessarily exposed to a harmful substance” when alternatives existed. He warned that Jansen’s conduct was “against the best public health practices,” that evidence now suggested exposure to asbestos fibres in the community was undesirable and that its use should be limited to “essential” purposes only. Prophetically, Major warned that homeowners would face a potential hazard from the leakage of fibres from the roof space into living areas.

Major admitted the evidence was not yet certain about the danger posed to the wider community from asbestos, but his cautionary message to the Department was clear – consider dissuading or even banning Jansen from using it.

Warnings then, and the growing body of evidence in the years that followed on the dangers of asbestos, did nothing to dissuade authorities from allowing him and his successors to operate for another decade.

Yet the Commonwealth did apparently accept the potential for harm. The ACT Health Services Branch made provision for free health checks including x-rays for the installers of the insulation, and went so far as to issue a public warning to installers in 1971 of its potential health effects. The danger was not ignored by Jansen’s rivals in Canberra’s insulation trade either; with Bradford Insulation advertising conspicuously from late 1968 that their Rockwool product was “free of harmful asbestos.”

For Dirk Jansen, Asbestosfluf was just another of the entrepreneurial endeavours he pursued from his luxurious home on Olympus Way in Lyons, itself insulated with Asbestosfluf.

A plasterer by trade, Jansen started a company called D Jansen & Co in July 1966 with his wife Thea. Primarily working in plastering and general trades, Jansen and his “gang” as he called them, worked on projects including the Woden Plaza, Woden Valley Hospital and the Lakeside Hotel. Between 1966 and the mid ‘70s, he sold industrial conveyor belts, leased construction machinery and was a wholesaler of home cleaning products to retailers including David Jones.

It was in 1967 that Jansen began expanding into asbestos, becoming the ACT agent for Asbestospray Corporation of Australia. Specialising in fireproof, thermal and acoustic insulation treatments, patents suggest these products contained the same two types of amphibole asbestos, amosite and crocidolite, that Jansen would use a year later for insulating homes.

Sometime in the following months, Jansen purchased a second-hand insulation pumping truck in Sydney. In 1968, he established Asbestosfluf Insulations, a subsidiary of D Jansen & Co, employing a manager named Calder and his son Dirk Jr. to install the material. The material was usually amosite, produced by EGNEP, the South African mining subsidiary of Britain’s Cape Mining Company, that had tellingly closed its last British asbestos factory the same year.

The material was shipped in 45-kilogram hessian bags bearing the name EGNEP and the shipping mark of James Hardie, whose chief chemist in 1968 confirmed the product’s origin.

Jansen is also believed to have used crocidolite (blue asbestos), detected during the Commonwealth’s eventual audit of Canberra homes between 1988 and 1989. A source familiar with Jansen’s legacy suggested he offered crocidolite as a “premium” choice to customers.

When and how Dirk Jansen came up with the idea to use asbestos as a loose insulation remains a mystery, one that Jansen’s family is thus far unwilling to shed light on.

Did his experience with Asbestospray inspire him to experiment? There is merit to this theory. In an exclusive statement provided by the British Health and Safety Executive, it can be revealed that a number of homes in the UK also contain loose-fill asbestos in ceiling cavities, installed by workers taking the raw material they worked with by day, to use as cheap insulation. The idea itself then was not unique.

It’s also possible another operator inspired Jansen, with newly revealed information casting doubt on the long echoed claim he was unique. A statement provided by NSW Health in May reveals another operator is noted as working in south-west NSW and potentially elsewhere in the late 1960s, though their identity is not recorded.

Gersh Major’s 1968 report reveals a company called Bowsers Asphalt in Rozelle had been using “asbestos in a similar manner in Sydney” for 13 years and was believed to be considering an expansion into Canberra at the time. Documents related to Asbestosfluf make reference to the length of time the material had been used and is consistent with when Bowsers Asphalt was said to have begun using it. NSW Health provided a statement stating it was unaware of any residential dwellings in the greater Sydney area that contain loose-fill asbestos insulation.

Jansen’s Asbestosfluf subsidiary spent six years insulating homes in Canberra and regional NSW, chiefly Queanbeyan, Bungendore and Yass, before a new company co-owned by Joseph Jansen, believed to be one of Dirk’s sons, took it over. In 1972 Joseph, of Buvelot Street, Weston, with business partner John Hetz, of Duffy, established J & H Constructions. In 1973, J & H expanded into insulation under the name J & H Insulations.

Jansen’s Asbestosfluf subsidiary spent six years insulating homes in Canberra and regional NSW, chiefly Queanbeyan, Bungendore and Yass, before a new company co-owned by Joseph Jansen, believed to be one of Dirk’s sons, took it over. In 1972 Joseph, of Buvelot Street, Weston, with business partner John Hetz, of Duffy, established J & H Constructions. In 1973, J & H expanded into insulation under the name J & H Insulations.

J & H rebranded “Asbestosfluf” as “Amoswool”, adopting advertising that was subtler and avoided reference to what the material was.

To customers though, the grand claims remained unchanged; an original quotation obtained from a homeowner this year proudly described Amoswool as “completely harmless”, non-irritating and CSIRO tested. By 1975 only Joseph’s address in Weston was still associated with the business. In 1979, reflecting changes to building regulations in the ACT, the material was finally taken off the market.

In 1991, Dirk Jansen reflected on the legacy two generations of his family were responsible for, speaking to the Nine Network’s Richard Carlton on “60 Minutes”. Asked if he regretted what he had done, he was unrepentant, uttering a single word… “why?”

Panic, politics and dissention

BY 1989, anxiety and calls for action over Jansen’s legacy were coming to a head. For the past decade, awareness had been growing about the dangerous substance now present in potentially thousands of buildings in Canberra and the region. For much of that time, the Commonwealth’s position in Canberra had been one of identification and containment.

The Department of Territories issued public warnings and offered free insulation testing to homeowners from at least 1984. A manual obtained from a Commonwealth departmental archive details the advice for homes containing Asbestosfluf; warning that the fibres would infiltrate the living areas of homes through paths such as vents and lighting fixtures. Their concentration would increase over time and their presence would be stirred by every draft from a door or window. Removal, the manual warned, would usually not be feasible, with any attempts to do so increasing the contamination and being unlikely to remove all the pervasive material.

Despite the advice, more than 30 homeowners chose to have the asbestos removed professionally before 1989, while anecdotal reports circulated of others attempting to do it themselves. For the Commonwealth, facing a potential health crisis, mounting public pressure and uncharted legal territory, removal became an inevitability. For the agency charged with designing and implementing that removal, the Asbestos Branch, there were no ready plans, no guidelines and no examples to learn from.

The Branch adapted the Worksafe removal code to this unique situation, requiring all “visible and accessible asbestos” be removed. It developed a dual encapsulation method, allowing workers to remove the material within a negative pressure environment, while protecting the work site from the elements using a robust outer shell.

A PVA seal was chosen to make the material the Branch knew would inevitably remain, as safe as possible. A group of four external health experts was consulted, three of whom supported the Branch’s solution, with the fourth feeling it went too far. This innovative solution came at a cost however, with the only local firm eligible to tender, BRS, and interstate company Gardner Perrot, the latter described by former Branch head Keith McKenry in an interview in June as “much more professional,” providing estimates between $40,000 and $60,000.

Publicly, the ACT Government signed off on the Branch’s program, yet privately there was dissent.

Local asbestos removalists lacked the skill and equipment to meet the high standard set and feared losing business.

During 1989, the ACT became self-governing and new Labor Minister for Urban Services Ellnor Grassby became responsible for overseeing the Branch’s removal program.

McKenry recalls the Minister being influenced by the advice of one removalist in particular, whose behaviour so concerned the Asbestos Branch, it reported his activities be investigated. This removalist argued the Asbestos Branch’s solution was too elaborate and too expensive, though he was not the only one in the community making that argument. Academics, journalists and representatives of various industry groups labelled the Branch’s plans wasteful and extravagant.

Grassby, who did not respond to a request for interview for this story, and Urban Services Department managers, agreed with the critics and questioned why this asbestos removalist could clean homes for $20k when the Asbestos Branch wanted to spend triple per home, despite larger economies of scale?

That this removalist used no containment structures, only rudimentary equipment, and was seen to enter roof spaces without a mask was the answer.

Seeking an alternative, the Department considered the idea of demolishing affected homes, purely to save on removal costs. However the Asbestos Branch opposed this option, arguing that safe demolition would require homes be cleaned first, negating any savings. McKenry recalls the option for demolition as a solution on health and safety grounds was not considered by the Branch.

Seeking an alternative, the Department considered the idea of demolishing affected homes, purely to save on removal costs. However the Asbestos Branch opposed this option, arguing that safe demolition would require homes be cleaned first, negating any savings. McKenry recalls the option for demolition as a solution on health and safety grounds was not considered by the Branch.

The Asbestos Branch’s program eventually prevailed, but was not exclusive. Homeowners, particularly those wanting urgent removal and who were not eligible for the government’s priority list, were still able to hire a licenced removalist and seek reimbursement from the government. While these contractors were meant to abide by the same standards as the public program, the Branch knew they didn’t have the capacity to do it as safely or as thoroughly. Frustrating the Branch further, they were initially prevented from any oversight of the private contractors’ work, the jurisdiction belonging to Building Control.

Meanwhile in NSW, comparatively little was done. The Commonwealth did not see itself as having a role; its part funding of the ACT program uniquely born of its status as former Territory administrator.

State and local authorities provided Queanbeyan residents with voluntary insulation testing programs between 1989 and 1996. Most of the premises in Queanbeyan known to contain Asbestosfluf were identified through these programs that analysed approximately 350 samples.

Past requests by Queanbeyan City Council for Federal and State funding of an ACT-style cleanup have been unsuccessful. The prevailing advice from the NSW Government to all homeowners with asbestos insulation is that it presents a minimal risk if the roof space is kept contained and not entered, mirroring the advice abandoned by the Commonwealth more than 25 years ago. Yass Valley, Eurobodalla or Palerang Councils did not respond to enquiries.

Now almost 50 years since Dirk Jansen introduced Asbestosfluf, with the hazardous material still in the homes of Canberra and beyond, an end game for this legacy may be near as individuals, community groups, experts and lawyers push to find a solution.

Adam Spence is a Canberra freelance writer, features editor of the national law journal “Obiter” and a final-year law student at the ANU. His work has been published in “The Punch”, “The Canberra Times” and “The Australian”.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply