“Canberrans tend to assume that this city came without a human cost,” write Greg Wood and Brian Maher in the “Canberra Historical Journal” (October, 2009) but, as their article explains, the creation of the new capital caused “profound economic, social and family dislocation” for the ACT region’s pioneers.

At first, local people assumed only good things would come from the new capital, but they soon saw the Federal Government’s policy on dealing with the Territory’s future residents would be “you get what you’re given”.

The problem was the inconsiderate way the new Australian Commonwealth acquired private land, taking decades to complete the process and paying far less than the properties were worth.

Of course, the policy made sense on paper but its implementation proved very unfair on the landholders, who included some of the battlers who’d been helped into land ownership by the NSW Government’s 1861 Robertson Land Acts.

Then there was the fact that nobody living inside the Territory would be represented in local, State or Federal government (in fact, despite living at the political centre of a democracy, it actually took until 1948 for ACT residents to get a voice in the House of Representatives, with “full representation” in 1965 and a senator in 1975).

Nevertheless, the early settlers stood up for themselves, forming the Federal Territory Vigilance Association in 1911 and taking their concerns straight to the Federal Government in Melbourne.

They eventually won a few minor concessions and some sympathy from top bureaucrats and politicians, but in the end they just had to get over it.

In the “Historical Journal”, Wood and Maher quote a young Master Shumack, who noted bitterly that “one law for the big man [and] another for the small man now operated”, with larger landholders able to negotiate higher prices, often using threats of legal action.

Wood and Maher conclude that the community of about 1500 people was “fractured and disbanded”, just as the Aboriginal community had been 80 years before that.

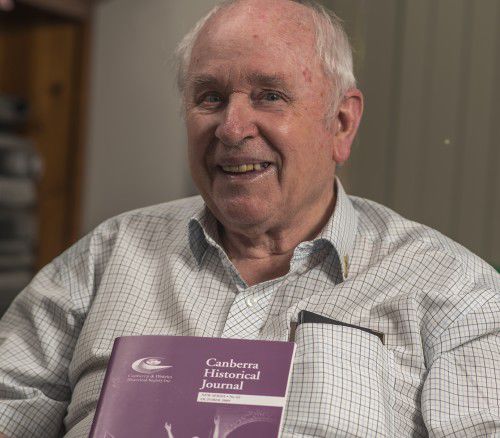

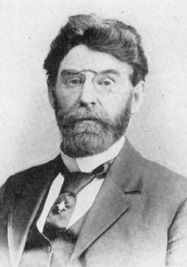

“They all got a raw deal,” says Maher, a retired Catholic priest whose historical and religious contributions earned him an Order of Australia Medal, and who just so happens to be the grandson of the Vigilance Association’s plucky president, Jeremiah Keeffe.

“I never knew him; he died in 1932 and I was born in ‘36,” he explains, immediately dashing our hopes of hearing grandpa’s stories about standing up to “The Man”.

“He hobnobbed with all the big guns – the Campbells, the Craces – but he was just an ordinary small farmer who’d had an education,” says Maher. “He’d had two years in high school at St Joseph’s College in Sydney, so he was a capable man; he was a smart cookie, apparently.”

He points out that the poorly handled land acquisition process did not affect enough people to become a big issue.

“They were voices in the wilderness, really. [World War I], I think, would have taken over a fair bit of the public interest in them.”

Their experience of the uncaring Commonwealth having left a sour taste, most chose to give up and move on rather than buy a new 99-year lease on their former land.

“You see, the feeling was they didn’t want to be under the Government’s thumb,” says Maher. “They all wanted to get outside the new Territory.”

ACT Shadow Heritage Minister Alistair Coe says he learned of the Vigilance Association a few years ago, doing research for his maiden speech, and notes how little has changed in the relationship between citizens and government.

“These pastoralists were understandably cautious about the Commonwealth Government potentially nationalising their land and they were strategic in their efforts to ensure that the process was managed properly,” says Coe.

“The challenges of how governments consult, provide information and appropriately compensate people adversely affected by their decisions are still relevant today.”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply