Photography / “Mervyn Bishop: Australian Photojournalist” at the National Film and Sound Archive until August 1. Reviewed by CON BOEKEL.

FOR millennia, Uluru nurtured its custodians and its custodians nurtured Uluru. Then came new words, the gun, and the camera. Uluru became “Ayers Rock”.

While some constructive camera work was done through proper engagement, busloads of tourists snapped a myriad photos of the custodians as if they were mere human curios. By way of contrast there is, to my knowledge, not one photo of any of the hundreds of massacres that frame Australian history. Absence of photographic evidence has an evidentiary quality all of its own.

Mabo led to land rights legislation, which led to land hand back, which led to the formation of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, which led to the formation of a custodian-majority Board of Management, which, in 1987, led to film regulations. Sacred sites were out of commercial photographic bounds. Mutitjulu living areas were off limits to tourist snappers. Some commercial crews embraced the changes. Other crews kicked back hard. They resented the power shift.

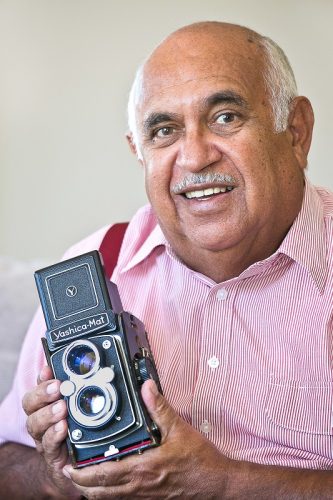

Around 1955, at Brewarrina, a 10-year-old Murri boy held a camera for the first time. The heart of the exhibition is about how Mervyn Bishop deployed the power of that camera and its successors. Fittingly, Bishop’s cameras are part and parcel of the exhibition.

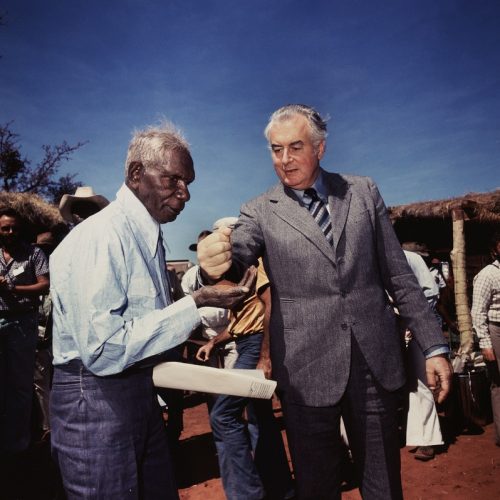

What of the photos themselves? There is the iconic “Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hands of traditional owner Vincent Lingiari, Northern Territory, 1975.”

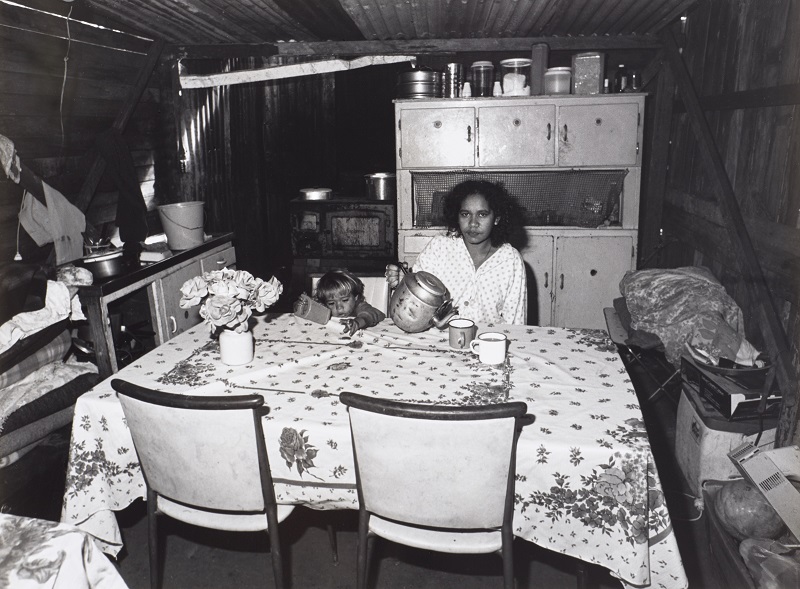

In some of his most powerful work, Bishop focuses on every day community life — often in terribly poverty-stricken surrounds. A woman stands straight-backed, looking at the camera, unblinking, with dignity, in the poignant “Woman standing near power cord in water, Burnt Bridge, 1988” and its counterpart, “Girl pours tea, Burnt Bridge, 1988.”

A bus has been converted into a makeshift shelter in “Bus stop, Yerrambie Reserve, Mt Isa, 1974”. There is a looming darkness in “Pool game, Burnt Bridge, 1988”. There is familial warmth in “Cousins, Ralph and Jim, Brewarrina 1966”. There is wit in “Bob’s catch, Shoalhaven Heads 1974”.

There is a masterful, technical and artistic achievement, in which light and shade fuse mob and country, in “Children playing in river, Mumeka, Arnhem Land, 1975.” “Jimmy Little – state funeral Kwementyaye Perkins, 2000” is profoundly moving.

The individuals in these photos trust Bishop and appear to be aware that the images have a significance beyond the moment.

The exhibition benefits from extensive selections from the National Film and South Archive and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Visitors are surrounded by still and moving images of Indigenous people and are immersed in the sound of Indigenous voices. Much of this material concerns ongoing struggles for justice and provides the context within which Bishop worked.

The exhibition is marvellous. It gains power from the pictorial and technical quality of the photos. Bishop is a pro. The images are honest, dramatic, disturbing, warm, domestic, intimate, as well as historic on an international scale. Much photo journalism has only a transient value. Not so Bishop’s photos. They are standing evidence for an important and unfinished business.

In 2017, through “The Uluru Statement from the Heart”, First Nations put an offer of peace talks on the table. One prerequisite was to be a mutual understanding of the truth about how words, guns and cameras were deployed and what the consequences were, and remain. There can be neither justice nor reconciliation without this. Through his photos, Bishop presents the audience with a major body of the necessary evidence.

The exhibition achieves handsomely its aim of celebrating Bishop’s career. It also reveals a humble but proud man. “Uncle” is a title of respect sometimes given to older and special men. Uncle Mervyn has, over a lifetime, used the camera to bear witness. The question that the exhibition asks is this: “Do non-indigenous Australians have the strength to accept the generous offers of First Nations and of Uncle Mervyn?”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply