“The ACT’s increase in debt is largely due to poor financial management and deficits in the primary cash balance which have of necessity been funded through borrowings,” say JON STANHOPE and KHALID AHMED in a supplementary piece to their ‘Deep in Debt’ series.

IN addition to general concerns about the impact the ACT’s current levels of debt will have on essential services, such as health and education, and the ethics of the burden of debt being transferred to future generations, we have been asked:

- where the borrowed monies have been spent, and what the ACT has to show for the debt;

- whether this is the full extent of the ACT’s financial obligations; and

- whether the debt figures include or paid for Light Rail Stage 1.

In relation to light rail, some readers suggested that because the project was “off budget”, or in the words of some “paying for itself”, it was unlikely to have an impact on the budget.

Noting the government is in the process of making contractual commitments for the next stages of the project, it’s timely to expand on and, hopefully, clarify issues relating to the funding of light rail.

Our previous articles related to borrowings by the government from the financial markets through bonds and promissory notes, and the lack of budgetary capacity to repay those debts as they mature.

However, in addition to borrowings there are other substantial medium to long-term financial obligations that will also need to be met from future budgets. Broadly these relate to superannuation liabilities and payments in respect to Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) into which the ACT government has entered.

The superannuation liability relates to the entitlements of current and past members of the ACT Public Service who were members of the Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme (CSS) and the Public Sector Superannuation Scheme (PSS).

The benefits payable to members of these schemes are defined in advance through formulae that are linked to factors such as years of service, final average salary and level of individual member contribution over time.

The defined benefit schemes are now closed to new employees, however, there are current employees who are members of these schemes as well as retirees receiving pensions consistent with the terms of those schemes.

The extent of the ACT’s superannuation liability is measured by actuarial assessments and depends on factors such as life expectancy, changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and assumptions on the take up of lump sum payments as opposed to a pension stream.

The 2020-21 ACT audited financial statements estimate the ACT superannuation liability as of June 30, 2021 as $13.2 billion. According to the projections included in the budget papers, the liability is forecast to peak in the early 2030s, reducing progressively over the following 50 years, based on the current mortality rates and other relevant assumptions.

Concerns about the ACT’s mounting superannuation liability were raised soon after self-government, resulting in a Superannuation Provision Account being established in 1991 to set aside funds for investment to cover future liabilities.

The Carnell government subsequently adopted a target, as part of its fiscal strategy, designed to fully fund the superannuation liability by 2030.

This target was maintained by subsequent governments and remained a key component of fiscal strategy until 2013-14. However, the 2014-15 budget reflected a major change in fiscal strategy, including changes to the measurement of debt and liability metrics that, as we have pointed out previously, are irrelevant and misleading.

The budget papers nevertheless continued to refer vaguely to the government’s objective to fully funding the liability by 2030, until the 2018-19 budget where the Budget Overview (rather than the Fiscal Strategy) contained the following rather ambiguous undertaking:

“The government continues to focus on our important financial objective of extinguishing the territory’s unfunded superannuation liability by 2030. This is the largest liability on the government’s balance sheet, but our strategy remains on target to fully fund this over time.”

Notably, there is no reference to any such objective or indeed a target date in the 2019-20 budget papers.

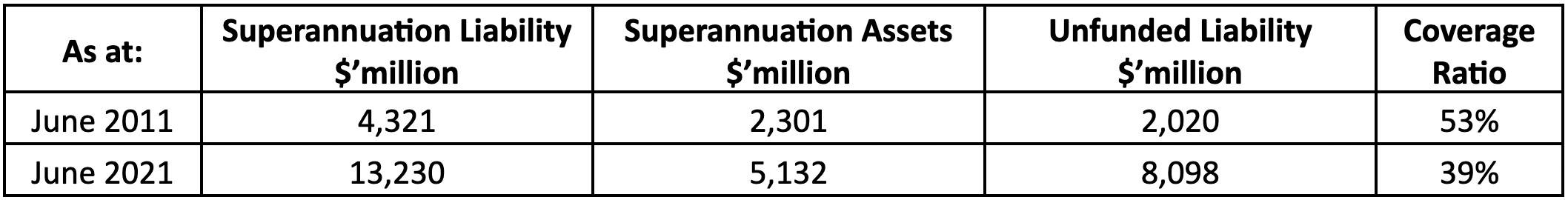

In 2010-11, the superannuation assets, that is, funds set aside previously and their returns, had reached $2.3 billion, while the liability was estimated at $4.3 billion (TABLE 1). The unfunded liability was $2 billion, and the coverage ratio was 53%.

TABLE 1

In 2021, the liability had grown to an estimated $13.2 billion, of which only $5.1 billion was covered, leaving an unfunded component of $8.1 billion and a coverage ratio of just 39 per cent.

There are “technical” considerations regarding returns from investments in prevailing financial market conditions, however, it is notable that budget allocations to the fund over the past decade have not kept pace with the growth in liability due, almost certainly, to the precarious state of the budget and the government’s spending priorities.

THE other most significant liabilities that the ACT government has acquired relate to two projects commissioned by it under PPP contracts. Typically, such arrangements are used for infrastructure procurement or delivery for the purpose of raising finance, divestment of risk to the private sector, and/or bundling services with the infrastructure provision.

The reality is that the appearance of “off-budget” financing is attractive, even seductive, to governments such as the ACT government, where debt levels on the balance sheet are a serious concern. Ultimately, however, such arrangements represent a cost to taxpayers and future budgets, in both the finance and service delivery component, as well as in project risks.

The accounting standards initially failed to ensure that the impacts of such “innovative financing” structures, as they were originally known, were appropriately disclosed.

For example, in 2015-16, when the ACT government entered into PPP agreements for Light Rail Stage 1 and the ACT Law Courts, the financial commitments were disclosed only in a note in the annual financial statements.

Presumably on the insistence of the auditors. The ACT’s monthly payments to its PPP partners cover (a) design, construction and upgrades of the infrastructure; and (b) operating and maintenance costs. The former has been treated as a finance lease and the latter as an operating lease until 2019-20.

At TABLE 2 are the commitments the ACT government has entered into over the term of the PPP agreements relating to Light Rail and the Law Courts.

TABLE 2

These liabilities will be extinguished over the respective terms of the PPP agreements.

APART from the liabilities discussed above, there are other relatively smaller commitments the government has made, for example, those relating to leasing vehicles, office space and IT equipment.

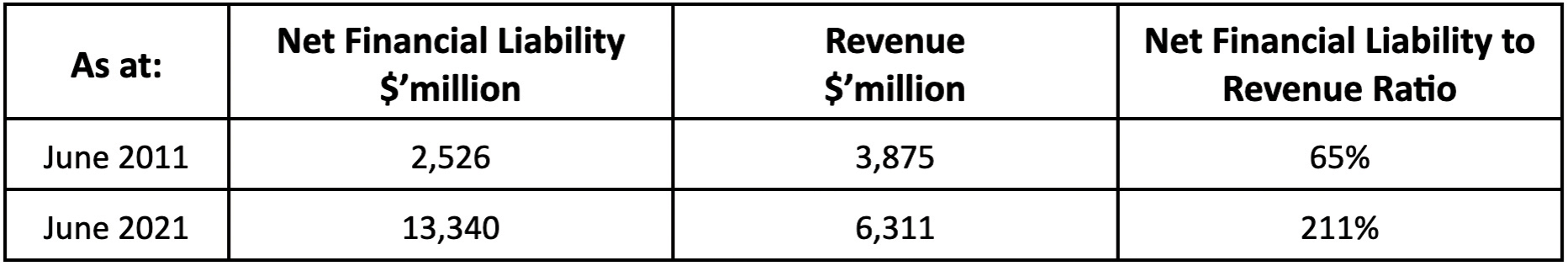

A broader measure of liabilities than Net Debt (which includes superannuation and other lease commitments) is Net Financial Liabilities (NFL) which is calculated as total liabilities less financial assets (such as cash reserves and investments). TABLE 3 illustrates changes in this measure over the last decade as well as the NFL to Revenue ratio, a key metric in the Fiscal Strategy.

TABLE 3

Note: The above table relates to the General Government Sector. For the total Territory, which includes some of the light rail liability, the NFL to Revenue ratio was 85% in 2011 and 236% in 2021.

To sum up, the ACT’s increase in debt is largely due to poor financial management and deficits in the primary cash balance which have of necessity been funded through borrowings.

In addition, the superannuation liability has increased by $8.9 billion, and the ACT government has abandoned the objective of fully funding the liability by 2030. The unfunded superannuation liability has increased four-fold over the last decade. The PPPs have placed significant liabilities on the budget over the coming years.

Jon Stanhope is a former chief minister of the ACT and Dr Khalid Ahmed a former senior ACT Treasury official.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply