IT is indisputable that Emily Kam Kngwarray is one of Australia’s greatest artists, as the coming exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, which bears her name, will show.

So famous is “Emily” that many people simply call her that, and yet when I catch up with Kelli Cole, co-curator of the exhibition with Hetti Perkins, I find that calling such a significant figure by her “whitefella” name could be considered disrespectful. Her own people refer to her as “that old lady, Kam”.

Names are very important in her Anmatyerr culture. Emily was her whitefella name and Kngwarray her skin name, but Kam is the name she was given at birth, and it refers to the seeds of the daisy yam, delicious when ground and a source of life itself.

Another matter needed clarification. Cole and Perkins saw how much of the critical comment around Kngwarray’s art depicted her as a kind of abstract expressionist artist.

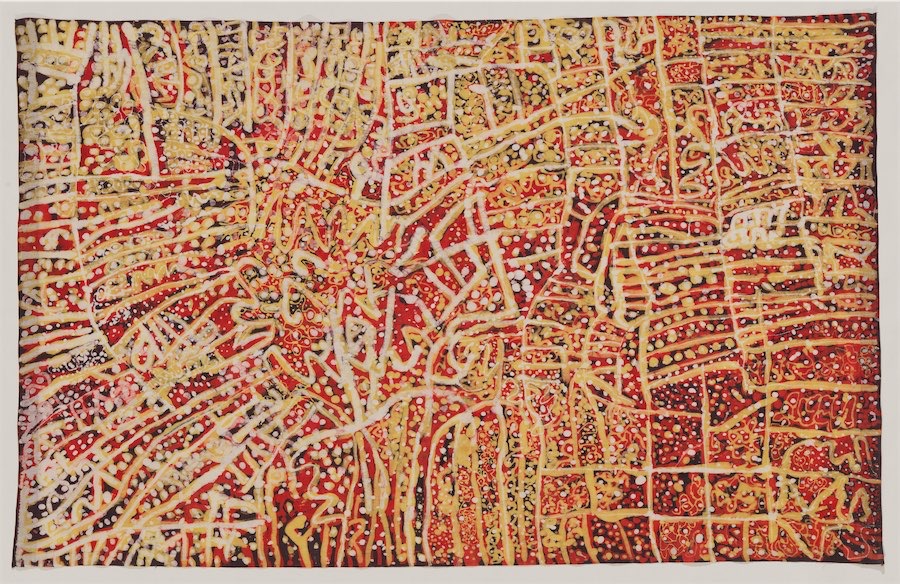

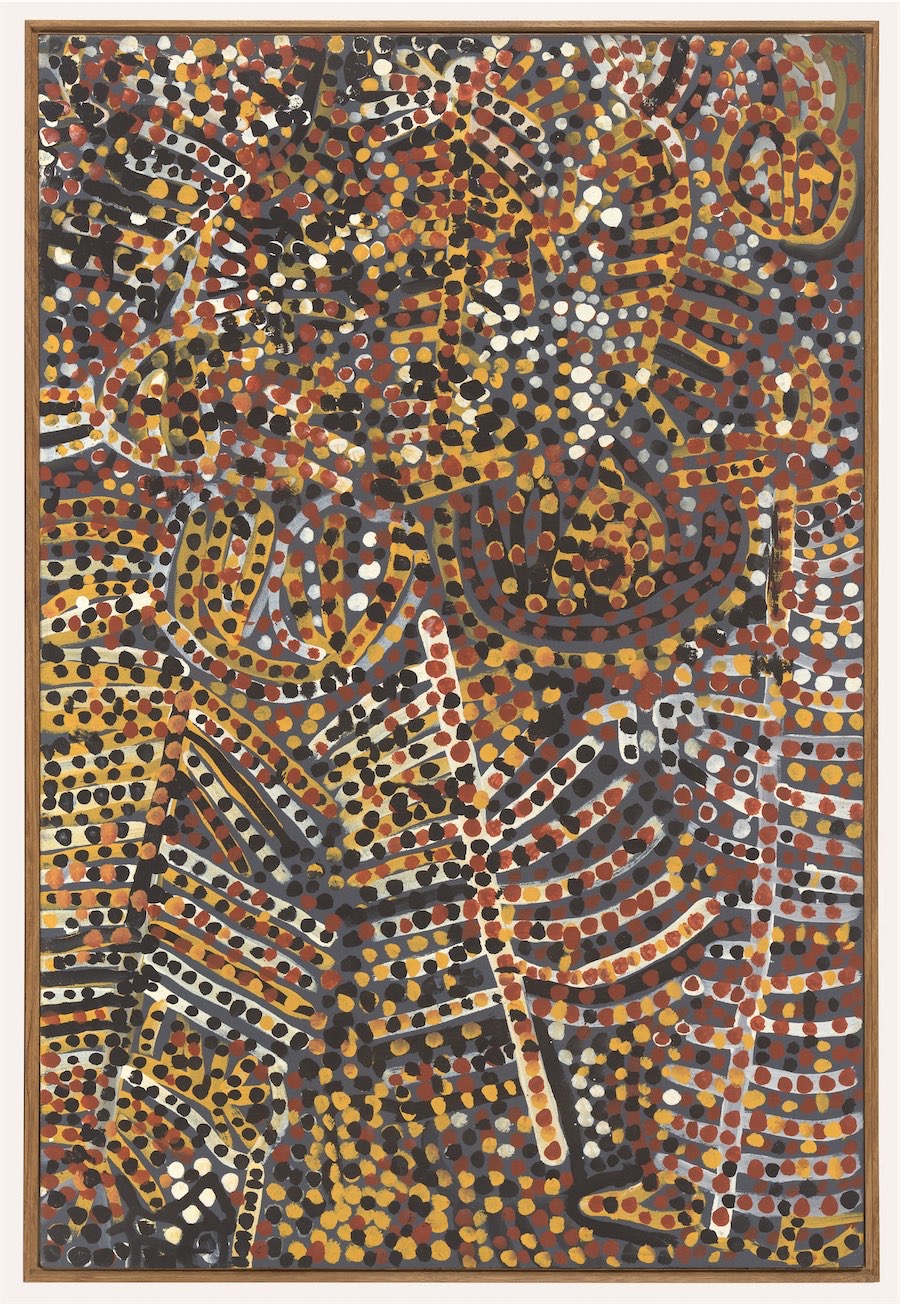

Here they turned to Kngwarray’s own community for confirmation that, in fact, she was drawing and painting not totems, but objects and animals quite literally related to her country, sometimes bringing the lines from women’s ceremonial face and body painting and the tiny dots that represent the yam seed into her art.

This exhibition is a dream come true for Cole who, when a teenager, through her uncle, the artist Robert Ambrose, met and watched Kngwarray and the women of Utopia, north-east of Alice Springs, as they created batik.

“I was always aware… that I was in the company of someone extraordinary… she was the epicentre of everything,” Cole says.

Of Central Australian Warumungu and Luritja ancestry, Cole has been 17 years at the NGA and has been involved in all the National Indigenous Art Triennials, including “Ceremony”, curated by Perkins. Together the two of them, who call each other “sis” and enjoy a good joke, convinced NGA director Nick Mitzevich of the necessity for them to spend time on Country.

Perkins now lives in Alice Springs, a good base for their revelatory foray in March 2023, when the women in Utopia were happy to look at the paintings and to identify the precise details of each. Luckily, their partner in mounting the substantial NGA catalogue, Jennifer Green, was fluent in the language.

Afterwards the ladies performed a ceremony involving five dancers who painted themselves, and danced, with Kngwarray’s recorded voice playing in the background.

“The ladies could tell us the story, they knew the stories, they know the old lady’s paintings and they know the living country – it’s theirs.”

The coming exhibition certainly features some of the late Emily Kam Kngwarray’s (the new, definitive spelling of the name) huge late paintings, but its focus is broader and focuses on the artist’s grounding in batik.

The art form, which reached its apogee in the courts of Java, had been brought to Utopia as part of a literacy program facilitated by Jenny Green and others in the late ’70s and Kngwarray, with her friend Gloria Petyarre, were part of the initial cohort who went on to found the Utopia Women’s Batik Group.

“Painting is the most highly prized art medium and people consider textiles to be craft, but we are arguing that through displaying her textiles, we can show her future as an artist,” Cole says.

“She was a batik artist for longer than she was a painter.”

With this in mind, the early part of the main exhibition will feature magnificent swathes of batik art on silk.

Emily and her cohort took to batik like ducks to water, until between 1988 and 1989, the flamboyant Rodney Gooch from the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association dropped off 100 canvases to Utopia.

He returned later to find that 81 paintings had been executed on those canvases, all but one by women.

The curved foyer part of the NGA will feature all 81 of those paintings, which Sydney dealer Chris Hodges sold to the Holmes à Court Collection before they were exhibited at the SH Ervin Gallery in Sydney.

Right from the start, “Emily” was identified as the outstanding artist. This was no accident, Cole says, as she had always been the senior culture woman, and was much older than some of the artists.

She was nearly 70 when she started with batik and began painting in her 80s, enjoying a short but brilliant career before her death at about 86 in 1996.

She met Paul Keating, was awarded an Australian Artist’s Creative Fellowship, posthumously represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1997. In 2017 her 1994 painting “Earth’s Creation I” was on-sold for $2.1 million.

But this is not an exhibition about fame and fortune; it is rather one where the women of Utopia have been consulted to identify exactly what Emily was painting – her country.

“Emily Kam Kngwarray,” National Gallery of Australia, December 2 to April 28.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![For graphic designer Tracy Hall, street art is like any artwork, her canvas has been swapped out for fences and plywood, her medium changing from watercolours to spray paint.

A Canberra resident for 13 years, Tracy has been a street and mural artist for the past five.

Her first exploration into grand-scale painting was at the Point Hut toilets in Banks five years ago. “They had just finished doing up the playground area for all the little kids and the words [of graffiti] that were coming up weren’t family friendly,” she says.

“So I ended up drawing this design and I got approval for the artwork.”

Many of Tracy’s time-consuming artworks are free, with thousands of her own dollars put into paint.

@traceofcolourdesigns

To read all about Tracy's fabulous street art, visit our website at citynews.com.au or tap the link in our bio! 🎨🖌

#canberranews #citynews #localstories #canberrastories #Citynews #localnews #canberra #incrediblewomen #journalism #canberracitynews #storiesthatmatter #canberralocals #artist #streetart #streetartist #StreetArtMagic](https://citynews.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sb-instagram-feed-images/490887207_1225841146218103_6160376948971514278_nfull.webp)

Leave a Reply