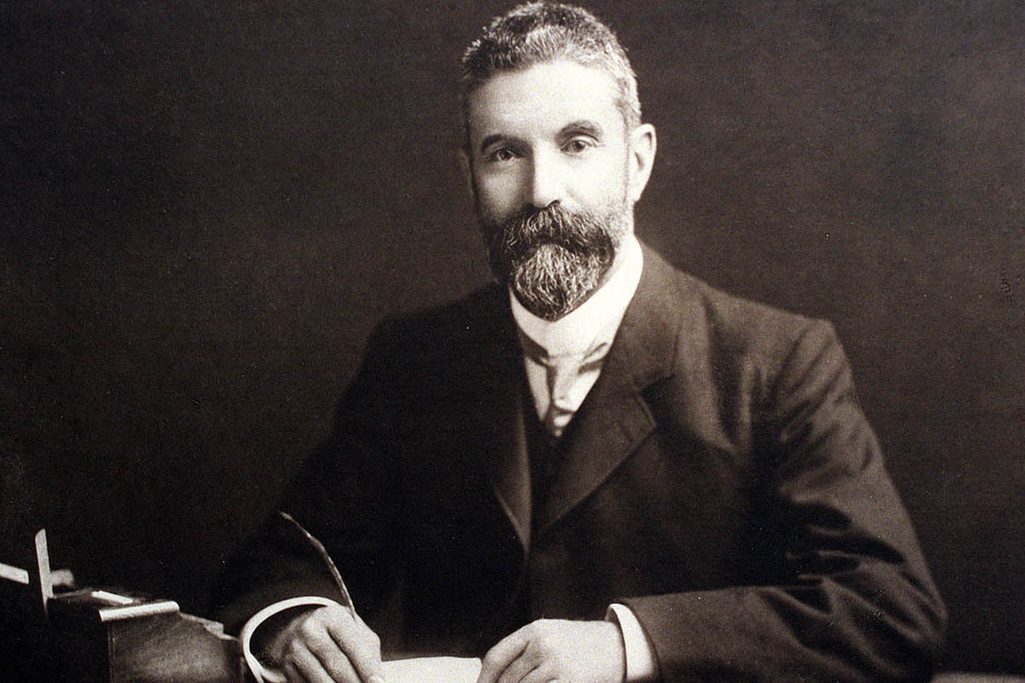

“As Australia’s second prime minister, Alfred Deakin celebrated a White Australia Policy and declared the Aboriginals a dying race, a victim of social Darwinism,” writes “The Gadfly” columnist ROBERT MACKLIN.

ONE of the many pleasant surprises of my researching the biography of Charles Weston, Canberra’s master arborist and horticulturist, has been the insight it reveals of the calibre and character of the men who wrote the Australian Constitution.

Weston arrived in Australia in 1896 while Federation was the big issue; and the Constitution was a product of the debate. It occurred to me that we could perhaps note the background of its framers when voting in the coming referendum to incorporate the Aboriginal people in our great and diverse community.

The two men who shouldered the vast majority of the drafting were the little-known Tasmanian, Andrew Inglis Clark, born in 1848 and Sir Samuel Griffith who entered the world three years earlier.

Clark’s Tasmanian roots began with his father, Alexander, a Scottish engineer who established himself in Hobart designing and building flour mills, water mills and coal mines for the settler population.

By then, the Aboriginal people had suffered the attempted genocide of so-called Black War, and the exile of the survivors to the Furneaux Islands.

Andrew joined the firm, became an engineer, then an articled law clerk and was called to the bar in 1877. The following year he entered the House of Assembly and quickly gained a reputation as a supporter of “universal suffrage” (though the Aboriginal people were not included in his “universe”).

He became his state’s attorney-general in 1888 and it was as a delegate to the 1891 National Australian [Federation] Convention in Sydney that he produced a draft constitution. He then joined the Queensland Premier, Samuel Griffith, on his steam ship “Lucinda” on the Hawkesbury River to edit his draft.

Griffith was the senior figure in the exchange, and we can assume that his amendments prevailed, except for the one referring to the appointment by parliament of a High Court, rather than the court being a constitutional requirement.

Clark won that battle and for that we might thank him for the Mabo decision and other progressive High Court decisions in the Aboriginal field that never occurred to him… and certainly not to Griffith.

Both men accepted the British government’s notion of terra nullius so there was no need to mention the previous owners of the land. And it was Griffith, as attorney-general then premier of Queensland (1883 to 1888 and 1891 to 1893) who authorised the notorious Mounted Native Police Force to conduct their Aboriginal massacres across the state.

After their 1891 edit, there were minor changes from NSW’s Edmund Barton, SA’s Charles Kingston and other state politicians, but nothing bearing on the Aboriginal issue. Alfred Deakin and others then negotiated with the British government which gave its imprimatur to the final draft.

As Australia’s second prime minister, Deakin celebrated a White Australia Policy and declared the Aboriginals a dying race, a victim of social Darwinism. “In another century,” he said, “the probability is that Australia will be a White Continent with not a black or even dark skin among its inhabitants.

“The Aboriginal race has died out in the south and is dying fast in the north and west even where most gently treated.

“Other races are to be excluded by legislation if they are tinted to any degree. The yellow, the brown, and the copper-coloured are to be forbidden to land anywhere.”

Happily, since then we have matured sufficiently to end the White Australia Policy, greatly to the nation’s benefit. The next step seems pretty obvious.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply