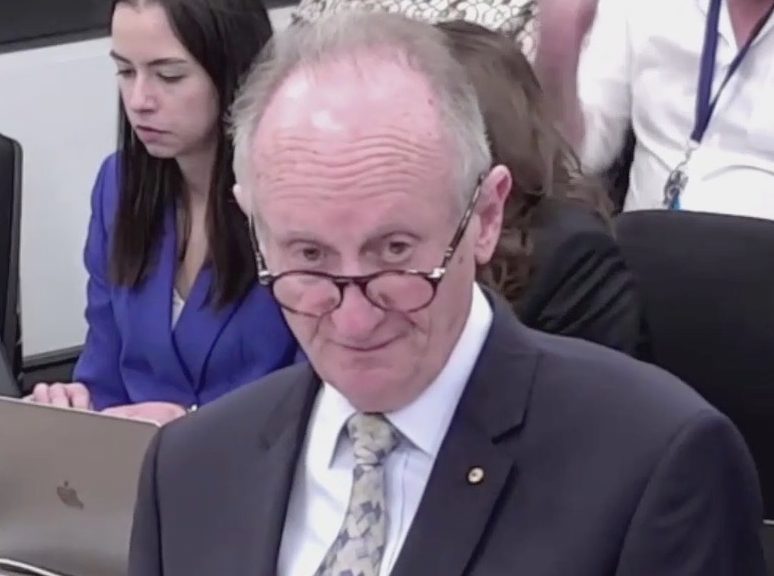

“CityNews” legal columnist and former barrister HUGH SELBY is commentating regularly on the Sofronoff Inquiry’s public hearings, focusing upon the advocacy and witness performances.

The Board of Inquiry, led by Commissioner Walter Sofronoff KC, a former president of the Queensland Court of Appeal, was established by the ACT government in December to examine how police, prosecutors and a victim support service handled allegations made by Brittany Higgins against her former colleague Bruce Lehrmann.

The rare treat of streamed adversarial entertainment

LONG, long ago – that’s pre-millennials (imagine that!) – there used to be inveterate court watchers, people who were often to be seen in the public gallery, watching a trial, observing the highs and lows of witnesses and advocates.

That was in the days when there was no court security, when you could take a thermos and a homemade sandwich and sit outside in the noonday sun, pondering the infinite range of human error that led to the courtroom.

Some of those watchers were generalists, whatever was on that day provided the day’s entertainment. But there was the rare bird who followed particular advocates, just as there are spectators today who follow their most liked fighter in UFC’s mixed martial arts (MMA).

Some readers will baulk at the juxtaposition of top advocates and crowd-drawing MMA fighters. Spare a moment to accept these similarities: highly paid, born with talent, that talent developed with hard work, recognised as winners, perform in a small physical space, subject to referee’s rulings, bring moments of thrilling surprise to their performance, and easily picked out from the other contestants.

This public inquiry has brought into the one room leading advocates from Queensland (as counsel assisting), NSW, the ACT and SA. It’s a rare treat to be able to watch them on livestreaming.

It’s all a question of how the question is formed…

“Mr Tedeschi uses the ‘Why did (something) happen?’ in his cross-examination. This is a classic “open question”… The standard, but wrong, instruction when teaching cross-examination technique is not to ask such open questions. Mr Tedeschi has avoided that error; however, he fell into another trap,” writes HUGH SELBY.

EARLY in the questioning of DPP Shane Drumgold SC by Erin Longbottom KC, senior counsel assisting (CA), an objection was made about her use, from time to time, of cross-examination technique.

Commissioner Walter Sofonoff KC allowed that approach on the basis that the rules of evidence as applied to trials do not apply to inquiries. Hence a CA is permitted to mix traditional types of questioning.

Quite so. However, from the perspective of effective questioning, it is better to use forms of question that are non-confronting with a witness from whom the cross-examiner wishes to elicit useful information, as distinct from forcefully “closing off escape routes” for that witness. Put more succinctly: wherever possible be nice. It pays off.

Monday’s questioning of Det-Supt Scott Moller by junior counsel assisting Joshua Jones illustrates the point. Unlike the earlier CA questioning DPP Mr Drumgold for a long time, this questioning was “soft” and non-confronting.

But the topic’s agenda was not clear. There came a time when the CA needed to move from the straightforward to the contentious. He did so by abruptly moving to “closed questions” that were confronting to the witness. What Mr Moller felt about that change, you and I do not know. However, we can ask how we would feel if someone who is treating us positively, then without warning, turns negative.

What the CA might have done was first to tell everyone, Mr Moller included, that he was about to ask questions about such and such and that these questions would “test” the witness. Rather than closed questions he could control the narrative by the following: “Let’s now turn to document X, looking at that document one interpretation might be such and such. Was that your intention?” The next question will be based upon the answer given.

To be or not to be a successful cross-examiner

At the start of Tuesday’s hearing Mark Tedeschi KC, advocate for DPP Drumgold, quite rightly raised with Commissioner Sofronoff the application of the rule in Browne v Dunn (a late 19th century British court decision).

“A very good practical question,” responded the commissioner. “Let me think about it”, he continued.

As Mr Tedeschi said: “In a trial I’d have to cross-examine, but here the rules of evidence don’t apply.”

Musing aloud the commissioner said: “We might have to proceed in the orthodox way” (ie, call all witnesses that Mr Tedeschi has to question because of conflict between their recollections and Mr Drumgold’s recollection of conversations. This is what is understood as required by the “rule”).

Following the lunch break, the commissioner indicated that the inquiry would follow the practice followed by the NSW ICAC to deal with that rule. He outlined that approach and advised that all parties would be provided with the written ICAC policy.

As he did last week, when he cross-examined Steven Whybrow SC (defence advocate for Bruce Lehrmann), Mr Tedeshi cross-examined with a good, slow pace. He uses questions that suggest the “wanted” answer. These are called “closed questions”. They are classic cross-examination techniques.

Unfortunately, Mr Tedeschi, like a number of his colleagues, uses the misleading question form, “I suggest to you…” This is a statement. It is not a question. A widespread common error in technique is still an error.

Mr Tedeschi also uses the “Why did (something) happen?” in his cross-examination. This is a classic “open question”, most often used when questioning one’s own witness. The standard, but wrong, instruction when teaching cross-examination technique is not to ask such open questions. Mr Tedeschi has avoided that error; however, he fell into another trap.

Such open questions can be asked when the worst possible answer will leave the questioner’s case no worse off. If the questioner sees their case as being on a losing path then more risky open questions can be asked. An answer may disclose something previously not noted that can be used to advantage. But an answer may worsen an already unhappy position.

Cross-examination about Heidi Yates

In Tuesday’s opening session Mr Tedeschi first pursued Mr Moller about the police decision to formally interview the Victims of Crime Commissioner, Heidi Yates.

That pursuit was a mix of closed and open questions. Nothing wrong with that. In some cases it delivers gold. This was not one of those cases. Each time he gave Mr Moller the chance to amplify he did so, with measured, credible information and tone.

“Did you deliberately neglect to do so and so…?”, followed by the suggestion that the interview of Ms Yates was done to prevent her being a support person: both propositions were emphatically denied.

Such questions are similar to: “You are a liar, aren’t you?” Expecting the answer: “Yes, you got me” is the last gasp of an unsuccessful cross-examination.

Cross-examination about second Higgins interview

The topic then shifted to the second recorded interview of Brittany Higgins. There were then too many questions that included, “could”, “potentially”, “might” (such and such) be confronting. There are large gaps between the possible, the probable and the proven. As Mr Moller correctly said: “You’d have to ask Ms Higgins”.

As has happened several times during the inquiry the commissioner then asked the advocate some telling questions as to the point of the line of cross-examination.

They were telling, not only for their import “Is this a good line?”, but also – for our purposes – because they show how useful it is for an advocate to clearly state each topic of questioning (both in chief and cross) so that the witness, the fact finder, and all other listeners are clear about what is going on.

Sadly, very few advocates share with the audience what they are about to do. Quite why there is this reluctance is unclear. An oft stated excuse is that it tells the witness what’s coming. So what? If the questioning is well-structured then signposting the path makes it more effective. If the questioning is poor in subject content and/or technique then it doesn’t get any better by being performed, as it were, in the dark on an unnamed road.

Matters came to a head with objections from two counsel that Mr Tedeschi was asking questions that not only lacked a factual basis but were at odds with what Ms Higgins said positively about police one week after that second recorded interview.

The commissioner allowed the questions on the basis that they were not reflective of Ms Higgins’ actual state of mind, but rather what should or could have been in Mr Moller’s mind at the time.

The questions continued, with Mr Moller being quite unfazed by them, until the livestream was muted for legal argument. That lack of success was emphasised by the commissioner saying shortly after the public hearing resumed: “You’ve exhausted the topic.” Soon after came the commissioner’s comment about some questions, that they were “better made in submissions”.

Ouch and ouch again and again

In response to a cross-examination question, Mr Moller was able to say that after he made the decision to charge, based on the DPP advice, the investigative team were absolutely committed to the prosecution. He was to repeat this answer.

This was a gotcha moment – but for the police, not the cross-examiner. Oh, dear.

This was followed by the responsive answer: “Mr Drumgold was going to prosecute this matter, no matter what.” Some minutes later he was to add that the DPP, “was dismissive (of the views of the investigation team)”. Again, oh, dear.

Then this answer came: “Mr Drumgold had lost objectivity… I thought it was best practice to get supplementary advice.” That’s a cross-examiner’s nightmare: his client’s assertions being done over repeatedly by the target witness.

To his credit, Mr Tedeschi can continue in the face of such adversity with unchanged pace, tone, or volume. There’s not even a facial expression to give away his internal feelings. One can envy any advocate who has a poker face.

Watching a fight, a spectator can have sympathy, even hopes for the underdog, willing them to get up and into the fight, although they have been knocked down repeatedly.

We all waited and waited as Mr Tedeschi picked up yet another document and asked questions that Mr Moller confidently, clearly rebutted. The referee, the commissioner, interjected as the questions continued. That was not to Mr Moller’s detriment.

It was telling that Mr Moller could turn towards the commissioner, that his face would relax, that he could be emphatic in his answers, that he could even thank Mr Tedeschi for a question (with a happy grin on his face), and that the commissioner would engage with him, sometimes, to clarify a point.

Telling again that Mr Moller said: “That was a great decision (by his superior to follow the DPP advice and charge)”. Mr Tedeschi ignored that answer. The commissioner didn’t miss it. He asked Mr Moller for an explanation.

There is an advocate’s fundamental rule: listen to the witness’s answer, reflect on how to use that answer, use the answer to the benefit of your case as it appears in that post-reflective moment. The commissioner has put that rule into practice so many times, but some others on their feet have not.

We all reached the lunch break. It was a long morning with a surfeit of repetition of earlier evidence, and the cross-examiner having failed – so far as I could hear or see – to land a single blow on the witness opponent.

But there’s always the next round and that was after the lunchtime interval. It was time for popcorn and a fizzy soft drink, or prosecco.

That invasion of privacy by the media

Following the commissioner’s Monday announcement that he had written to the editor of “The Australian” newspaper about a photo that invaded a witness’s privacy, the senior CA announced that the editor had replied. That reply was tendered. The commissioner then thanked the editor for her considered response and said that the matter is closed.

The cross-examination of Moller continued

More of the same on Tuesday afternoon: revisiting earlier evidence and Mr Moller being confident and clear in his answers. For example: “We are human, Mr Tedeschi, we are affected by pressure”.

The question for we observers is what is the purpose of this cross-examination? Please bear in mind that the commissioner and the CA have more insights, based on their mastery of all the documents.

Cross-examination can sometimes be described as a dress rehearsal of key parts of an advocate’s later closing submissions to the fact finder. Because of that it is useful to clearly state the purpose of lines of questioning – at least with enough clarity that the fact finder knows the ultimate point.

Mr Tedeschi would only say: “Moving to a different topic”. That’s a line without content.

Following DPP Drumgold’s evidence we can surmise that cross-examination by his advocate would be directed towards promoting the reasonableness of all or part of his actions or, as another option, minimising any negative findings, or, yet another option, both of those aims.

It may have been fruitful to take a cross-examination line that on their face the content and timing of some documents and acts by police was unusual. Mr Moller admitted as much on several occasions. That could be the basis for a submission that events misled the DPP.

But what happened was a broad-based attack upon the police work. That attack, as cross-examination, failed from start to finish for two reasons.

First, Mr Moller was credible. Second, there was no upside in Mr Moller’s answers to Mr Drumgold’s presumed claim to have acted reasonably in all the circumstances. Instead, the police position improved. A hint that others might share this view is that nearly all other advocates in the room were silent, seeing no reason to take any objection.

A further hint was when the commissioner asked Mr Tedeschi: “Where are we going with this?”. Hint not taken.

(Very late on Tuesday the commissioner was to say to Mr Tedeschi in the context of the accepting and rejecting of evidence: “It’s all about me”. Listen, reflect, reset.)

Mr Tedeschi demonstrated different recollections by Mr Moller and defence counsel Mr Whybrow of a phone chat between them about the “Moller Report”. Nice, but so what? It is clear from other evidence that the AFP was not claiming client legal privilege over that document.

It is trite that a document created for one non-privileged purpose does not become hidden from disclosure (ie, privileged) because it is attached to a request for legal advice.

Moreover, there is a sequence of communications that show that the AFP had told the DPP over some period that the AFP was not claiming “privilege” (this last point was well demonstrated by Ms Kate Richardson SC, advocate for the AFP).

Tomorrow will bring perhaps one more hour of Mr Tedeschi’s cross-examination of Mr Moller. Mr Tedeschi can review Tuesday’s transcript and apply all his extensive knowledge of advocacy: “What more, if anything, should I ask this witness?” Another counsel has expressed a wish to then cross-examine Mr Moller.

“CityNews” legal commentator and former barrister Hugh Selby is writing running commentary on the Sofronoff Inquiry’s public hearings, focusing upon the advocacy and witness performances. The “CityNews” coverage of the inquiry, including his daily reviews, are here.

Hugh Selby is the “CityNews” legal affairs commentator. His free podcasts on “Witness Essentials” and “Advocacy in court: preparation and performance” can be heard on the best known podcast sites.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![For graphic designer Tracy Hall, street art is like any artwork, her canvas has been swapped out for fences and plywood, her medium changing from watercolours to spray paint.

A Canberra resident for 13 years, Tracy has been a street and mural artist for the past five.

Her first exploration into grand-scale painting was at the Point Hut toilets in Banks five years ago. “They had just finished doing up the playground area for all the little kids and the words [of graffiti] that were coming up weren’t family friendly,” she says.

“So I ended up drawing this design and I got approval for the artwork.”

Many of Tracy’s time-consuming artworks are free, with thousands of her own dollars put into paint.

@traceofcolourdesigns

To read all about Tracy's fabulous street art, visit our website at citynews.com.au or tap the link in our bio! 🎨🖌

#canberranews #citynews #localstories #canberrastories #Citynews #localnews #canberra #incrediblewomen #journalism #canberracitynews #storiesthatmatter #canberralocals #artist #streetart #streetartist #StreetArtMagic](https://scontent.cdninstagram.com/v/t39.30808-6/490887207_1225841146218103_6160376948971514278_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=MUiEmedc4VAQ7kNvwHTUMX_&_nc_oc=Adk-5HjcsfQwB-n_l8zetmr0YqMaupGjrl2gNVCZdsmkxwn-oqjBg_V7pLtGggCE43s&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=lk7Qw5VY5nGWNxucgGQIcw&oh=00_AfHgLo3_2lgw0iPelrQfv0ce2TJCtzpPmRmvKXjj65V4vQ&oe=680AE354)

Leave a Reply