THE National Museum of Australia is exploring what it means to be “Aussie” in a new poster exhibition.

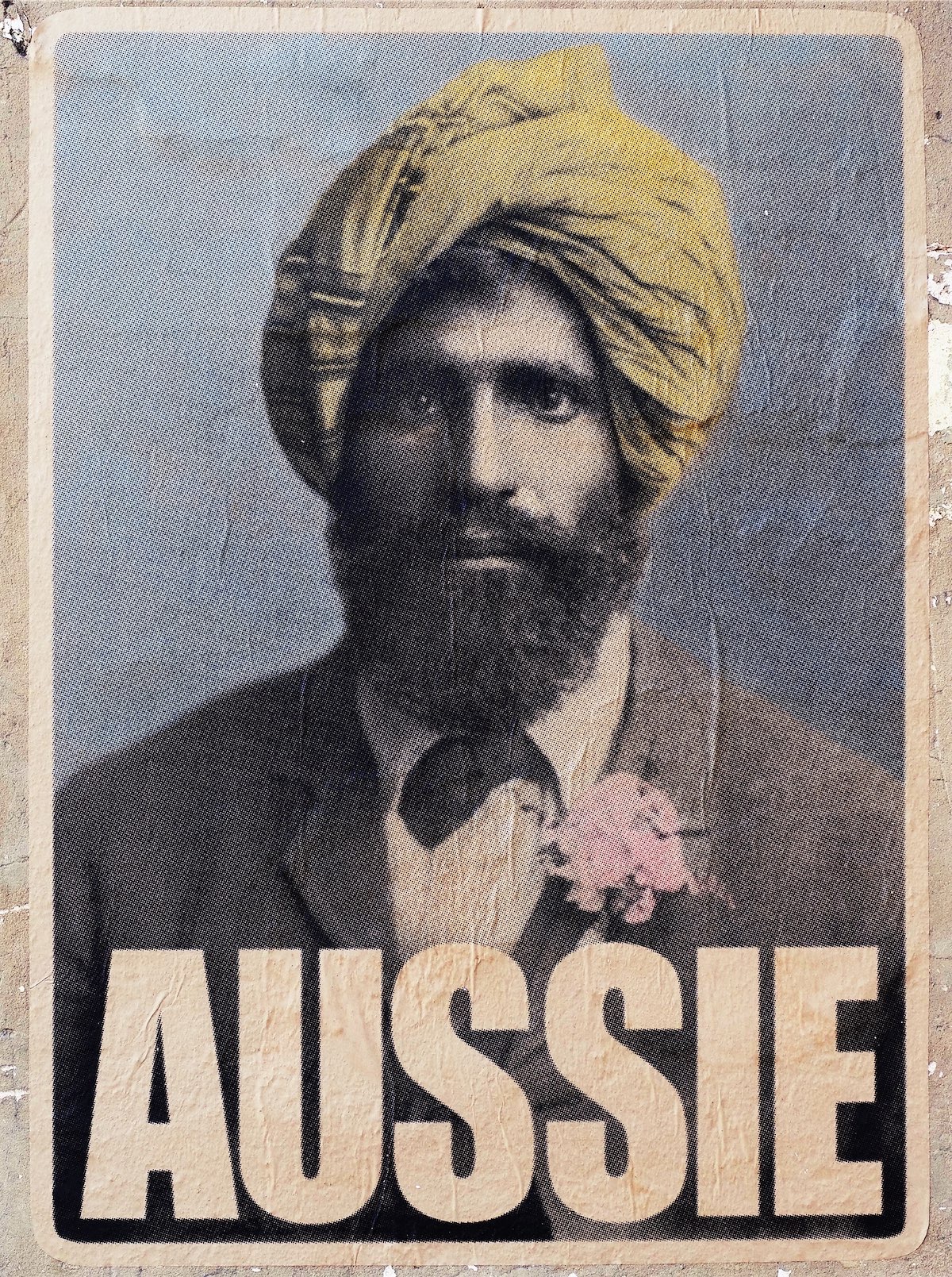

“Aussie Posters”, a new exhibition showcasing the work of artist Peter Drew, looks at diversity and exclusion through a series of posters that feature archival photographs of individuals who applied last century for exemption from the then Australian government’s notorious dictation test.

That’s the one where under the Immigration Restriction Act, applicants had to write 50 words in a language of the immigration officer’s choice, which could be given in any European language. If they failed, they could be deported. It was a cruel, cynical joke perpetrated on generations of would-be immigrants, most of the “wrong” colour.

Drew has taken archival images in the National Archives and created street art posters by overlaying them with the word “AUSSIE”.

He has been displaying his posters on the walls of Australian cities and towns since 2016, inviting passers-by to look them in the eye to discover the stories behind the faces of non-British migrants entering Australia after 1901.

The individuals featured in the posters were Australian-born or had lived here for many years. To travel overseas and not be subject to the dictation test upon their return, they had to apply for an exemption or else face having their re-entry rejected.

Drew says his posters respond to rising racism and xenophobia in Australian public culture.

While most of those on the posters got the exemption and eventually returned to Australia, some did not, such as 22-year-old Kanichi Shiosaki, born on Thursday Island in Queensland, who sought exemption from the dictation test in 1931 so he could travel to Japan. His return to Australia was not recorded.

Another, Bejah Dervish came to Australia to work as a cameleer, having been born in Baluchistan, now in Pakistan. In 1896 he managed the camels used for transport on the gruelling Calvert Scientific Expedition to the Great Sandy Desert of north-central WA. After, Bejah settled in Marree, a railhead near Lake Eyre in SA with a large cameleer community and Australia’s first mosque. In 1930 Bejah retired to grow date palms. He died in 1957.

Gum Yook Lee travelled with her infant son Charlie to China from Cairns, Queensland, in 1922. They returned five months later. Charlie had been born in Cairns, his mother in Brocks Creek, NT. On the exemption application, Charlie left his tiny handprint, his mother her thumbprints.

Muslim hawker Monga Khan, who arrived in Victoria in 1895, travelled around Melbourne, Ballarat, Beaufort and Ararat selling local and imported goods. In 1916, aged 46 years and in poor health, he applied for exemption from the dictation test so he could visit his family in British India (present-day Pakistan). Supporters vouched that Khan was “honest and industrious, sober and most respectful”. The exemption was granted, allowing him to return to Australia and continue his business. He died in Ararat in 1930.

“I like exhibiting art on the street because public space is a great equaliser, an ancient forum, and it allows people to connect in a very raw way,” Drew says.

“When we gaze upon the other and feel their gaze returned, we recognise oneself within the other and, for a moment, all boundaries dissolve. That’s my aim.”

“Aussie Posters”, Mezzanine Gallery, National Museum of Australia until August 27.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![Evie Hudson is a woman with amnesia, who forgets the last 13 years. Piecing her life back together, she navigates the harsh realities of coercive control.

Evie is the leading character in local author @emmagreyauthor's second novel Pictures of You.

Her debut book, The Last Love Note, sold more than 100,000 books worldwide within a few months of being published last year.

“I think that using amnesia really helped [show the effects of coercive control] because she had that sense of being completely lost in her own life,” Emma says of her new work of fiction.

To read the full story and find out more about this fabulous local author and her latest novel, visit our website at citynews.com.au or click the link in our bio! 📚✒️

#canberra #local #canberralocals #canberralife #australia #author #localauthor #Picturesofyou #coercivecontrolisabuse #dvawareness #bestsellingauthor #canberraauthor #localnews #citynews](https://citynews.com.au/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)

Leave a Reply