ON Thursday, I spent an extraordinary 30 minutes sitting in a lower space at the National Gallery to watch the national collecting institution’s latest acquisition, a huge, moving sculpture by American artist Jordan Wolfson, titled “Body Sculpture”.

Less a sculpture in the conventional sense than an animatronic production, it could be dismissed as what one bystander called “a very expensive piece of gadgetry”, but armed with some prefatory words from NGA director Nick Mitzevich, I saw it otherwise.

This is one of the gallery’s very rare commissions (the last one was “Skyspace” by American artist James Turrell in 2010 and there is another one underway by Australia’s Lindy Lee) and is one that should be visited by adults and kids alike— and definitely by dancers.

All will be fascinated by Wolfson’s artistic use of robotic engineering, masterminded by his collaborator, Mark Setrakian, the robot master behind “Men in Black” and “Hellboy”, who was on hand to reveal that he had a very close relationship with the worlds of dance and music.

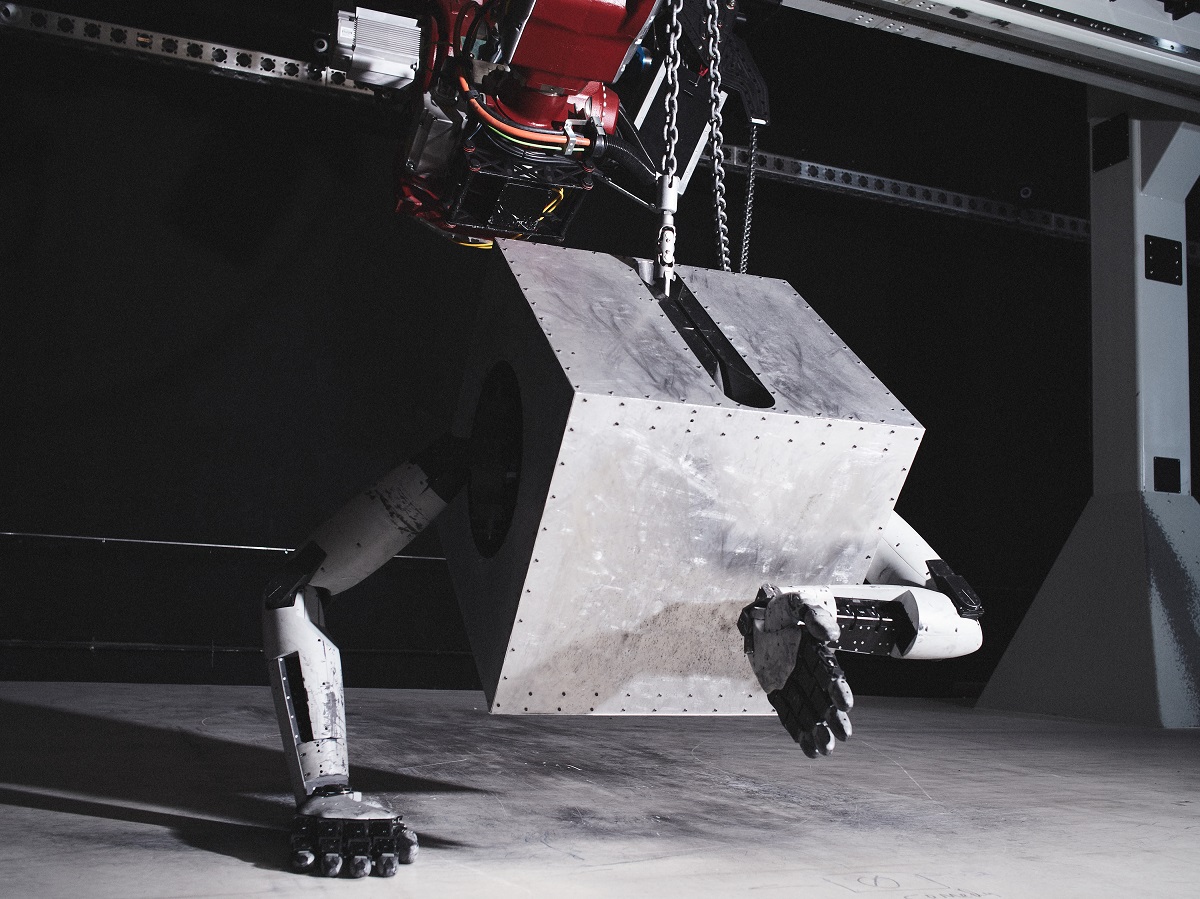

That explains much of the 30-minute sculptural presentation, which commences with a loud click, after which a chest-like mental metal box with two robotic hands protruding from it, took centre stage to perform a series of subtle movements.

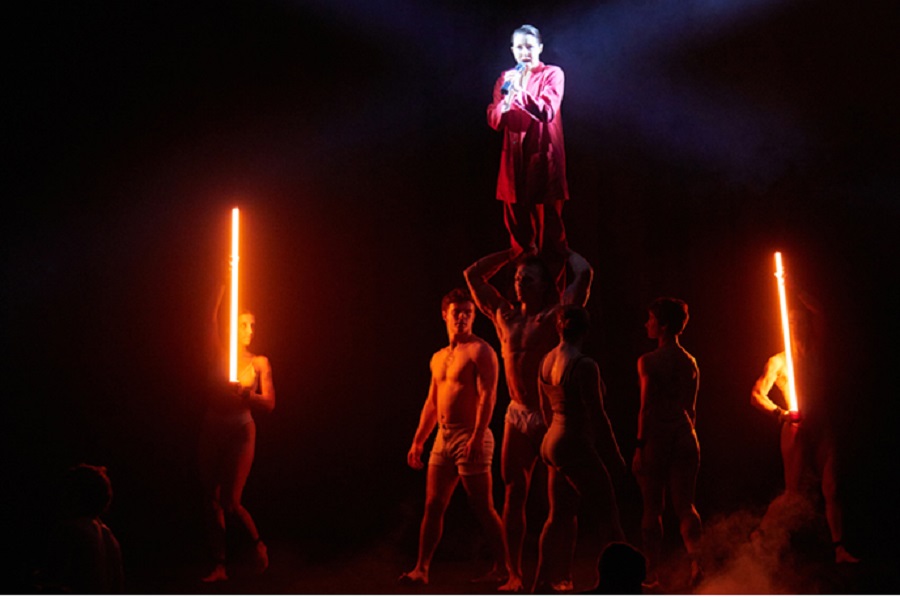

From my perspective, it resembled nothing less than a scene from the ancient Japanese Noh dance-theatre as the hands slowly moved to touch the ground, so slowly in fact, that it redefined one’s view of motion. This was consistent with the artist’s aim to reach a deeper register of audience feeling.

Gradually, with the robotic technology, an array of chains and motors, which hung omnisciently above, there was a slow shift, a gradual movement of the left arm, the twitching of a few “muscles” before the flexing of those muscles extended into the hands.

Here again, I was reminded of dance, in this case the complex “mudras” (hand language) of the classical Indian Bharatanatyam, for, although at first the flat of the hand was used, it was not long before we realised that each digit was entirely flexible.

Indeed, in one series of movements where the thumb and the other digits were moving in opposition to each other, the “Body Sculpture” was able to achieve far more flexibility than I could when I attempted to copy it.

Incidentally, there was no head and there were no legs.

Suddenly, the robotic “controller” from above, moved speedily to stage left dragging the body sculpture with it. This elicited a series of chest beatings, this time, putting me in mind of some of the more aggressive movements in masculine Indonesian dance.

For what followed, animatronic though it might have been, was undoubtedly a dance expressing savage anger at being so manipulated.

The rest of the 30 minutes was taken up with variations on this theme, with body and controller in opposition, leading at one stage to absolute chaos where music came more to mind, as one hand drummed an insistent rhythm while the other gesticulated helplessly, only to join eventually in the rhythmic beating.

The 30 enigmatic minutes finished as quickly as they had started, with a loud click.

This is the first solo presentation of Wolfson’s work in Australia and “Body Sculpture”, Mitzevich told us, is a project that’s been more than five years in the making, ever since Jordan approached him in New York with a proposition.

The sculptural presentation is adjacent to a room that features video footage of other intriguing works by Wolfson and Setrakian in which the full potential of animatronics can be seen close up, often showing intimate facial gestures, along with a suite of Australian artworks that had inspired Wolfson.

In the end, I was inclined to agree with Mitzevich that this is an important piece of art, one that connects it with the 21st century and one in which, as Wolfson says, “elicits the viewer to become activated in their bodies and therefore present.”

Jordan Wolfson, “Body Sculpture”, NGA until April 28, 2024.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply