JOHN MINNS looks back at the decade since then-PM Kevin Rudd ruled that those arriving by boat to seek asylum would never settle in Australia. And every successive government has agreed.

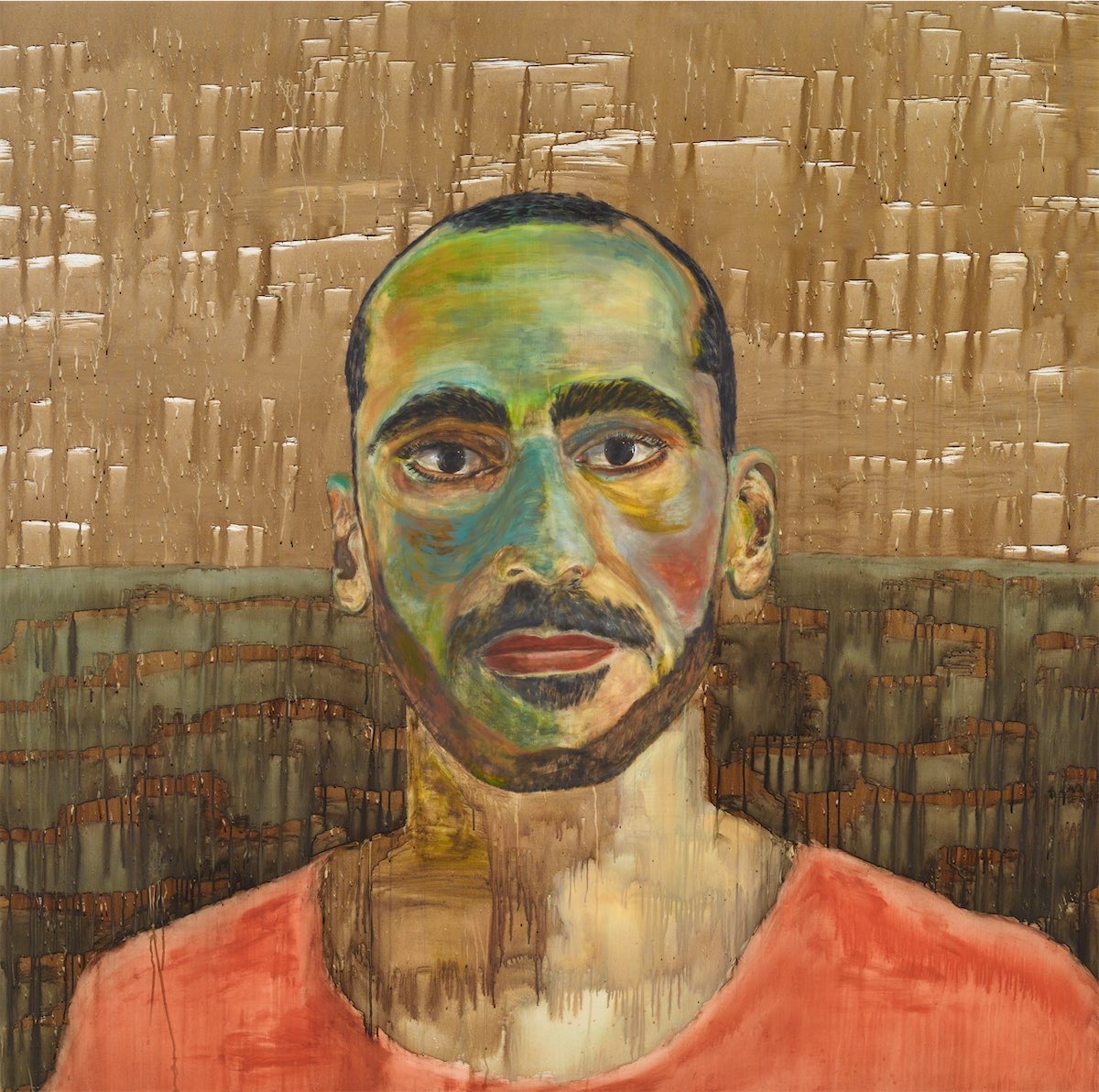

MOSTAFA Azimitabar is, by any measure, a talented person. Known as Moz, his self-portrait reached the finals of the Archibald Prize.

He’s a musician as well, performing with rock legends such as Midnight Oil and composing his own songs.

Recently, he starred in a documentary film titled “Freedom is Beautiful” and was also an executive producer on it. It received a standing ovation at the recent Sydney Film Festival. This is a person who surely would make a valuable contribution to Australian society. But current government policy is that he will not be allowed to do so.

Moz is a Kurdish democracy activist who had to flee Iran 10 years ago to seek safety. Because he arrived by boat, Australia locked him up for eight years for no crime – first on Manus Island and then in hotel detention in Melbourne. This month Federal Court judge Bernard Murphy found that, while legal, his detention in hotels “lacked ordinary human decency”.

After 2737 days in detention, Moz was finally released on a temporary bridging visa. But the government still has shown no signs of providing him or many others in his situation with permanent settlement in this country. Moz will speak at a protest in Canberra on July 23 to share his experiences of the last 10 years.

The protest is happening because this month marks 10 years since Kevin Rudd’s government ruled that those arriving by boat to seek asylum would never settle in Australia.

On July, 19, 2013, at a press conference with PNG Prime Minister Peter O’Neill, Rudd said that: “From now on, any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees.”

Since then, Rudd has denied that this policy was meant to continue indefinitely and said that it should not have been renewed after one year. He argued that: “At the expiration of 12 months, if we were not able at that stage to identify an appropriate place where asylum seekers could be located, then Australia would have had a responsibility to locate them elsewhere, including Australia, if other places could not be identified.”

Although the original agreement with PNG did provide for reviews after 12 months, there was no suggestion in it, or in other statements made by Rudd at the time, that Australia retained responsibility for the asylum seekers or that they might be resettled here.

In the offshore detention system after 2013, overwhelming evidence piled up of serious abuse, medical negligence, and high levels of self-harm. The leaked “Nauru files” catalogued around 2000 incidents that illustrated this happening. About 100 Australians employed in it became whistle-blowers. There were 14 deaths during this time.

Whether or not it was Rudd’s intention that offshore detention should last for only one year, the fact is that every government since, including the current one, has refused to allow any of the thousands of people sent offshore to the camps on Manus Island or Nauru to settle permanently in Australia.

More than 1000 people medically evacuated from Nauru and PNG are now in Australia on bridging visas, which must be renewed every six months. Many of these are young people – but their visas do not allow them to study after the age of 18.

After five years on Nauru and a medical evacuation to Australia, last year Sahar Ghasemi won a scholarship to study Law. Like thousands of others around the country she enrolled for first year full of hope. Seven weeks later she was disenrolled. Her crime – she had turned 18.

There are still 80 people in PNG who were in the Manus Island detention centre. The Australian government denies any responsibility for them. And despite the arrival in Australia of all remaining refugees from Nauru, the Albanese Labor government will continue to spend up to $350 million a year to keep the Nauru detention facility open. Interestingly, the British government’s attempt to emulate Australia’s offshore detention policy – with Rwanda as their equivalent of Manus Island or Nauru – has just been declared illegal by the Court of Appeals.

About another 9000 people in Australia are denied permanent visas because they failed the so-called “fast-track” assessment process introduced by the previous government.

Until granted permanency after the last election, the Nadasalingham family from Biloela were in this category. Under “fast-track”, success rates in asylum applications plummeted. It is no wonder. The process involves a 60-page form, only five additional pages of supporting material are allowed and there is just one – often 15 minute – interview. Appeals do not take into account any information not in the original application and there are no new interviews. The ALP’s Federal Platform calls for the abolition of the “fast-track” system. But, in government, they have not done so. If the system is unfair, as Labour recognises, then surely those who have been the victims of it should be dealt with differently now. Most of these people have no pathways to permanent resettlement anywhere. Like those who were on Manus Island or Nauru they live in limbo.

It is time to give people who have been stuck in limbo for up to a decade, a permanent home right now!

John Minns is emeritus professor of Politics and International Relations at the ANU and a member of the Refugee Action Campaign in Canberra. Refugee Action Campaign Canberra is holding a public rally – “Refugees in Limbo: 10 years of trauma” – at the intersection of Northbourne Avenue and London Circuit, 1pm, July 23.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply