What is the full story behind the payout to Brittany Higgins? Did the government follow the rules? Legal columnist HUGH SELBY has forensically pieced together all the prevailing directions and legislation and still finds the attorney-general’s justification wanting.

THINGS can become “curiouser and curiouser”, as was said by Alice in “Alice and Wonderland”. How else can the federal government’s handling of the reported multi-million dollar payout to Brittany Higgins be characterised?

This article shares public information about how the Australian government can and should manage claims for money damages. Ms Higgins made such a claim.

Such claims must be dealt with in accordance with the Legal Services Directions 2017 along with the applicable guidance notes.

If those directions are inapplicable, then the provisions and regulations governing “act of grace” (also known as ex-gratia) payments come into play.

For these we go to section 65 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and section 24 of the 2014 rules.

Based on what little has been published, there are grounds (explored here) to believe that the standard directions have been ignored.

Moreover, if the claim – for unexplained reasons – was treated as an “act of grace” payment, then evidence of compliance with the relevant rule has never been put forward. Note that an “act of grace” basis is contrary to the Attorney-General’s claims this month, which are set out late in this article.

Two telling contrasts to the settlement

First, a recent example of a department following the Legal Services Directions.

In 2022 the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) recommended that the government pay compensation to a refugee.

The sustained complaint was the use of force by camp staff that exacerbated a prior injury while the complainant was in an off-shore immigration detention camp.

The Department of Home Affairs rejected the recommendation as follows:

“The department disagrees with [the] recommendation… The Commonwealth can only pay compensation to settle a monetary claim against the department if there is a meaningful prospect of legal liability within the meaning of the Legal Services Directions 2017 and it would be within legal principle and practice to resolve this matter on those terms.

“Based on the current evidence, the department’s position is that it is not appropriate to pay compensation in this instance.” (See Mr AO v The Commonwealth (Dept of Home Affairs) [2022] AusHRC 145, at para 67.)

Second, an example of an application for an “act of grace” payment being refused.

In Ogawa v Finance Minister [2021] FCAFC 149 the AHRC had recommended $50,000 compensation for the failure by the Commonwealth to find less oppressive detention methods.

Dr Ogawa made an application to the Commonwealth by reference to the AHRC report. She applied for an act-of-grace payment, but the finance minister, responsible for the operation of the PGPA Act, refused to make the payment, as it was said (by the Department of Home Affairs) that no law was broken by the Commonwealth, and there were no “special circumstances” (as are required under section 65) warranting a payment. [paragraph 27]

The Full Court pointed out that section 65 is very wide, so wide that on the facts a decision to permit the payment was also possible. [paragraph 29] A legislative note to the section states: “A payment may be authorised even though the payment or payments would not otherwise be authorised by law or required to meet a legal liability.”

Legal requirements to settle claims

Readers need to be aware of the following requirements before claims against the Commonwealth are settled pursuant to the Legal Services Directions or the “act of grace” provisions.

The Legal Services Directions 2017 are a set of binding rules issued by the attorney-general about the performance of Commonwealth legal work.

“The directions set out requirements for sound practice in the provision of legal services to the Australian government. They offer tools to manage legal, financial and reputational risks to the Australian government’s interests.”

The Directions can be found here.

For our purposes the important bits are the following (with emphasis added):

- The relevant entity is to report as soon as possible to the attorney-general on significant issues that arise in the provision of legal services, especially in handling claims and conducting litigation. These issues will include matters where: the size of the claim, the identity of the parties or the nature of the matter raises sensitive legal, political or policy issues (section 3.1.(a)).

- Monetary claims covered by this policy are to be settled in accordance with legal principle and practice, whatever the amount of the claim or proposed settlement. A settlement on the basis of legal principle and practice requires the existence of at least a meaningful prospect of liability being established. In particular, settlement is not to be effected merely because of the cost of defending what is clearly a spurious claim. If there is a meaningful prospect of liability, the factors to be taken into account in assessing a fair settlement amount include:

(a) the prospects of the claim succeeding in court

(b) the costs of continuing to defend or pursue the claim, and

(c) any prejudice to government in continuing to defend or pursue the claim (eg a risk of disclosing confidential government information) (Appendix C, paragraph 2).

- Any settlement requires the agreement of the Attorney-General (section 3.2).

- The relevant entity is to comply with any instructions by the Attorney-General about the handling of claims or the conduct of litigation (section 4.1).

- The entity is only to agree that the terms of settlement are confidential and cannot be disclosed where this is necessary to protect the Commonwealth’s interests. Before imposing or agreeing to such a condition, the entity is to satisfy itself, including by raising the matter with a party requesting the condition, that the condition is necessary. The entity should also seek to incorporate an exception to enable voluntary disclosure of the settlement (in whole or in part) to the Parliament or to a Parliamentary Committee (section 4.5).

- If the entity considers that a claim raises exceptional circumstances which justify a departure from the normal mechanism for settling a claim…the attorney-general may permit a departure from the normal policy, but may impose different or additional conditions as the basis for doing so (Appendix C, paragraph 5).

The directions come with guidance notes. Guidance Note #7 deals with “significant issues”. One of the specific categories is, “it raises legal, political or policy issues that receive or are likely to receive media attention or cause a significant adverse reaction in the community”. [paragraph 9]

Among the rules made for the PGPA Act is the following, significant requirement, set out in section 24:

If the finance minister proposes to authorise the payment of an amount under subsection 65(1) of the Act; and the relevant amount is more than $500 000, then before making the authorisation, the finance minister must consider a report of the advisory committee established in relation to the authorisation.

Outcomes and explanations

Ms Higgins’ allegations referred to early 2019 and the settlement was in mid-December 2022, some 3.5 years later.

Ms Higgins engaged lawyers and she made a claim for compensation arising from her allegations of being sexually assaulted in Parliament House and there being an inadequate workplace response.

The claim is wholly within the Legal Services Direction’s “monetary claim” provisions; however, the direction requirements seem to have been ignored as follows:

- The outcome breaches the direction on confidentiality. The media release on the day of the settlement reported that the government agreed to Ms Higgins’ request for confidentiality as to the terms and the amount. There was no valid reason to agree to that request.

- Her payment, as reported in the media, was around $3 million. Ms Higgins said that it was less.

Articles critical of the payment – and directed to matters going to liability and proof, clearly identified within the above extracts from the Legal Services Directions – have pointed to:

- the lack of any discernible legal basis for a large payment, or even any payout;

- the absence of any evidence to support any claim;

- the subsequent release of information such as the CCTV footage at the Parliament House security check that shows both parties to be sober enough, and

- Chief of staff Fiona Brown’s detailed, persuasive demonstration that work management had been fully supportive of Ms Higgins.

All of these matters strongly support an argument that had the matter gone to court Ms Higgins would have lost.

Despite concerns as to the justification for a payment increasing as more information came to light, the government has pushed back against any transparency or accountability.

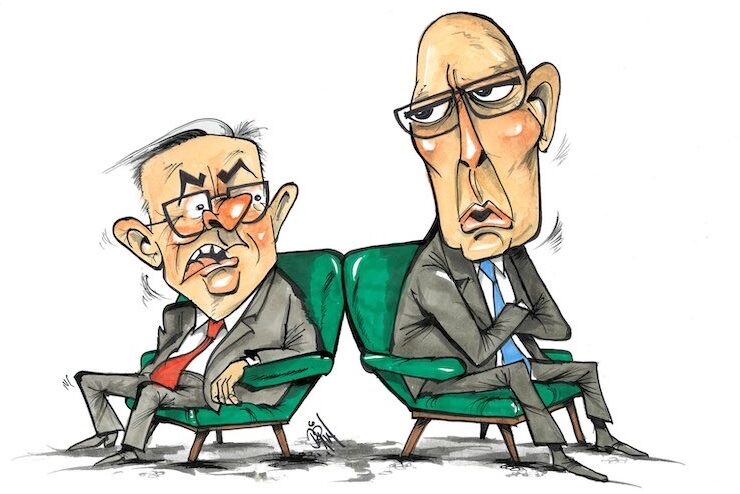

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus was interviewed early this month. He said that he was the decision maker, that he was “absolutely comfortable” with the payment, that it complied with the Legal Services Directions, and that it was absolutely standard that in some cases there was confidentiality as has happened here, that it was very common to settle cases with confidentiality, that it’s very common for it to be in the Commonwealth’s interests that there be confidentiality.

He then suggested that this was a mediated settlement. He emphasised that Finance Minister Katy Gallagher had no part to play.

Ms Gallagher has stated that she had no contact with the Attorney-General about the payment.

There can be settlement negotiations between parties with no mediator present. If there was, as suggested by the attorney, a mediator, who was she or he?

A “meaningful prospect of liability by the Commonwealth” is required under the directions. By what steps was that established in the absence of two Coalition senators and chief of staff Brown?

In December it was public knowledge that Ms Higgins was not able to give evidence. DPP Mr Drumgold SC told us that. How then were her claims to be tested?

This year it has been reported that Ms Higgins is able to give evidence for the media defendants to Bruce Lehrmann’s defamation claims.

While it’s wonderful that she has made such a strong recovery, it does call into question the bases of any settlement that included future inability to work etcetera.

Compare what the attorney-general said early this month with the legal requirements and factual matters set out above. Try as I might, I am unable to reconcile the two.

I wonder whether the attorney-general gave any instructions – as he can – to those acting for the government at the settlement meeting. If so, what were they?

Next week the National Anti-Corruption Commission opens its doors. Not a day too soon.

Hugh Selby’s free podcasts on “Witness Essentials” and “Advocacy in court: preparation and performance” can be heard on the best known podcast sites.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply