Dreading footy season? You’re not alone – 20 per cent of Australians are self-described sport haters, say HUNTER FUJAK & HEATH McDONALD.

With the winter AFL and NRL seasons starting, Australia’s sporting calendar is once again transitioning from its quietest to busiest period.

For many, the return of the AFL and NRL competitions is highly anticipated. But there is one group whose experience is very different: the approximately 20 per cent of Australians who hate sport.

We are currently conducting research to better understand why people feel this way about sport and what their experiences are like living in a nation where sport is so culturally central. We have completed surveys with thousands of Australians and are now beginning to interview those who have described themselves as “sport haters”.

Australia, a ‘sports mad’ nation

Australia has long been described as a “sports mad nation”, a reasonable assertion given the Melbourne Cup attracted crowds of more than 100,000 people as far back as the 1880s.

Australia’s sport passion is perhaps most evident today from the number of professional teams we support for a nation of 26 million people, one of the highest per capita concentrations in the world.

In addition to our four distinct football codes – Australian rules football, rugby league, rugby union and soccer – we have professional netball, basketball, cricket and tennis. In all, there are more than 130 professional sport teams in Australia today (across both genders).

Australia also hosts – and Australians attend – major sport events at a rate wildly disproportionate to the size of our population and economy. Formula One, the Australian Open, the National Basketball League, the National Rugby League and Matildas have all recently broken attendance or television viewership records.

Why people hate sport

The ubiquity of sport in our culture, however, conceals the fact that a significant portion of people strongly and actively dislike sport. Recent research by one of the co-authors here (Heath McDonald) has begun to shine light on this cohort, dubbed “sport haters”.

Sport haters account for approximately 20 per cent of the Australian population, according to two surveys we have conducted of nearly 3500 and more than 27,000 adults. Demographically, this group is significantly more likely to be female, younger and more affluent than other Australians.

Their strong negative sentiments are reflected in the most common word associations study participants used to describe sport. In the case of AFL, these were: “boring”, “overpaid”, “stupid/dumb”, “rough”, “scandal” and “alcohol”.

While the reasons for disliking sport vary from person to person, research shows there are some common themes. The first is in childhood, where negative experiences participating in sport or attending games or matches can lead to a life-long dislike of all sport. As one professed sport hater said in an online forum devoted to men who don’t like sport: “My brother would force me to play soccer against my will all the time as children. I think that is where my resentment for physical sport comes from because the choice was taken away from me by my twat of a brother.”

Sport hatred can also derive from social exclusion or marginalisation. Sport has historically been a male-centric domain that celebrates masculinity and can lead to toxic behaviour, which can exclude many women and some men.

Sport has also had to overcome racism, perhaps most symbolically visible by AFL player Nicky Winmar’s iconic protest in 1993. In addition, individuals with a disability still face barriers that result in lower rates of sport participation.

Here, the current Taylor Swift effect is noteworthy. The singer’s attendance at National Football League games, including the Superbowl, resulted in huge spikes in television viewership. Through her association, Swift helped make the sport more psychologically accessible for many women and girls.

The cultural dominance of sport also fuels its detractors, with many critical of sport’s media saturation and its broader social and even political prioritisation. (The debate in Tasmania over the controversial AFL stadium proposal is a good case in point.)

From a media perspective, Australia’s particularly strict anti-siphoning laws have ensured that sport remains front and centre on free-to-air television programming.

Sport’s cultural dominance also fosters resentment for overshadowing people’s non-sporting passions and pursuits, as well as creating societal out-groups. Journalist Jo Chandler’s 2010 description of moving to Melbourne is no doubt shared by many: “In the workplace, to be unaligned is deeply isolating. Team tribalism infects meetings, especially when overseen by male chiefs. In shameful desperation, I’ve played along.”

In life, it’s fairly easy to avoid most products you might dislike. But given sport’s ubiquity, simply tuning out is sometimes not an option.

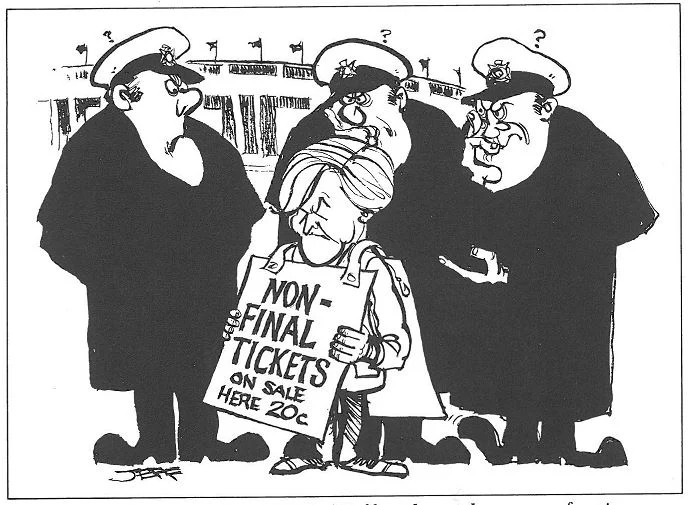

The Anti-Football League, a club for haters

In 1967, two Melbourne journalists, Keith Dunstan and Douglas Wilkie, launched an anti-sport club in response to this growing cultural dominance. In his founding address to the Anti-Football League, Wilkie made clear who the club was for: “All of us who are tired of having football personalities, predictions and post mortems cluttering our newspapers, TV screens and attempts at alternative human converse – from beginning-of-morning prayers to the last trickle of bed time bathwater – should join at once.”

Membership quickly reached the thousands. Soon, a Sydney branch was launched, bringing national membership to a high of around 7000. According to sport historian Matthew Klugman, members found joy in being “haters”… “they wanted to find a shared meaning in their suffering, not to extinguish it, but to better enjoy it”.

This led to some curious rituals, with members ceremonially cremating footballs or burying them. An Anti-Football Day was also launched, taking place on the eve of the Victorian Football League Grand Final.

The club would go on to experience periods of both prosperity and hiatus over the years, but has been dormant since Dunstan’s death in 2013.

With eight more years to go in Australia’s so-called “golden decade of sport”, which began with 2022 Women’s Basketball World Cup in Sydney and culminates with the 2032 Brisbane Olympics, it may be time sport haters to start a new support group.

If you consider yourself a sport hater, and are interested in contributing your experience to our ongoing research, please provide your contact information here.![]()

Hunter Fujak, Senior Lecturer in Sport Management, Deakin University and Heath McDonald, Dean of Economics, Finance and Marketing and Professor of Marketing, RMIT University. Republished from The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply