Opera / Hamlet, by Brett Dean, libretto by Matthew Jocelyn. At Sydney Opera House, until August 9. Reviewed by HELEN MUSA.

Brett Dean’s Hamlet is a grim, purposeful version of the world’s most famous play – make no mistake, this is a mighty musical achievement.

Nothing like the articulate tragedy-with-a-touch of-comedy that we have been used to on our stages, it is a sombre revenge tragedy, but one with Dean’s powerful music front and centre.

Within the confines of the Joan Sutherland Theatre there is little room for grandeur, so the artistic team used the two upper boxes on either side of the stage to house members of the chorus, horns, a trumpet or two and soft percussive instruments to create a surround-sound.

Dean’s music, handled with energy and sensitivity by conductor Tim Anderson, is largely dramatic, as he steers clear of major arias to represent the action in a moving musical landscape.

If there are arias, they belong to Claudius (Rod Gilfry) when he tries to pray and to Lorina Gore as Ophelia in her affecting mad scene, stripped of the lyrical ditties in the Shakespeare text in favour of snippets from Joyce’s favourite soliloquies.

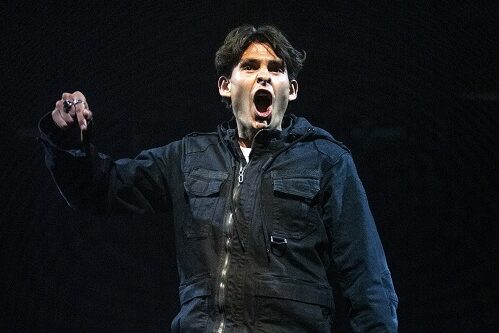

Commanding the stage throughout is Allan Clayton as an unmistakably enraged Hamlet in what will probably be his last appearance as the melancholy Dane.

Gore, delicate and fragile in the first act but coarse, sexually provocative and sardonic in the second, gives a perfect delineation of mental breakdown caused by psychological repression. Like Clayton, she commands the stage and it is clear that both librettist and composer have found her character worth exploring more than most.

The other actors fall into the shadows behind them.

Gilfry is mild-mannered as the King/villain, a nice enough fellow it seems, except for the fact that he has murdered his brother.

Catherine Carby carries the part Hamlet’s mother Gertrude with aplomb and perfect articulation, but remains a cipher, so we never know how much she knows about what the King is up to. Her movements also seemed to be confined within a stiff, formal costume,

Jud Arthur makes a welcome return to the stage as the ghost of Hamlet’s father, looking as if he been freshly dug up from his grave, with bits of grave matter plastering his body.

This is not a very funny Hamlet. Dean has introduced a quirky note of humour to the players’ scene through specially composed music for Scottish/Australian accordionist James Crabb, who drew titters of recognition from the house.

But as Hamlet’s old university friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Russell Harcourt and Christopher Lowrey were only mildly amusing and, stripped of their malevolence, gave us little idea what they were doing in Denmark.

Maybe the story of Prince Hamlet, known for his pathological inaction, was never suitable subject matter for opera.

Shakespeare’s play is full of psychological subtlety and double meanings. Not so much in this opera.

Director Neil Armfield’s answer to the aforementioned problem is to make the courtiers complicit in an authoritarian regime so that he often has the full chorus lined up obediently, including in the magnificent final scene where they registered palpable horror.

And yet the opera is strangely devoid of the two-faced political conniving and mask-wearing of the original.

Hamlet was a collaborative venture before its 2017 performance at Glyndebourne, and no doubt Armfield, there from early days, had a hand in getting the script down from around five to around three hours.

In cutting down the action, they eliminate the invading Norwegian lord Fortinbras and Hamlet’s pirate-ridden voyage to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, whom they keep alive until the last scene, when they join the body-count on stage. But they keep in Hamlet’s lengthy reflections on Yorick’s skull.

Matthew Joyce has a field day. In the players’ scene, he replaces Hecuba’s speech with snippets from “What a piece of work is a man!”

Snatches of that are reprised throughout, along with his favourite lines, “What is this quintessence dust?” “The readiness is all”, “Oh what a rogue and peasant slave am I” and “Never, never, never”.

Most daring of all, he looks at the play’s most famous line and instead, uses the words, “To be or not to be, ay, there’s the point,” words taken from the First (“Bad”) Quarto version.

Surely he intended to provoke the audience; this was Shakespeare worn with a difference.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply