Theatre / After Rebecca, by Emma Gibson. At ACTHub, Kingston, until March 23. Reviewed by HELEN MUSA.

Out of the bare bones of Daphne du Maurier’s (and Alfred Hitchcock’s) Rebecca, former Canberran Emma Gibson has crafted a powerful narrative about coercive relationships.

Gibson rejects the romantic narrative of the silent, suffering husband, Max de Winter and his poisonous late wife, Rebecca, depicting him in her script, relocated to outback Australia, as a rich pastoralist.

The evocative soundscape conjures up a remote and dangerous world.

An unrelenting exploration of male violence towards women, the play turns the tables on du Maurier, who by no means sided with her female characters.

Gibson has come up with a gripping, unpleasant narrative.

Despite that unpleasantness, it kept me on the edge of my seat for 65 minutes.

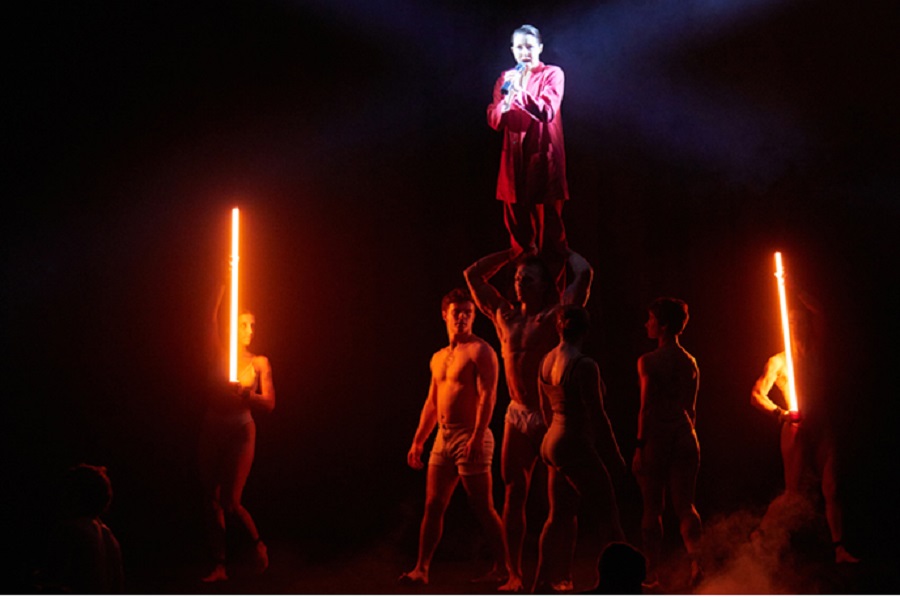

Her play is bookended with du Maurier’s famous words: “Last night, I dreamt I went to Manderley again,” performed by Michelle Cooper as the protagonist/narrator.

But Cooper is no shrinking violet like her counterpart in the novel and film, but is a spirited, at times aggressive, storyteller who is keen to stand up for herself but is somehow incapable of doing so. This was not always convincing.

The odds are stacked against the protagonist – a remote location, powerful lawyers and no friends.

The audience pick up the warning signs faster than she seems to. When Max throws away her phone and promises her an expensive new one which never arrives, then misbehaves when she’s ordering dinner, the picture becomes clear to us of a man used to having his own way.

There is no subtlety or nuance in this, Max is a pale-eyed, manipulative swine, through and through.

One or two elements from the book and film remain. There is the costume party in which the heroine ill-advisedly appears in a get-up worn by the late Rebecca. Also, the fearsome Mrs Danvers, played in the Hitchcock film by Australia’s Dame Judith Anderson, is transformed into the station manager Danny, who at least has a soft side to him.

It seemed a pity Gibson didn’t end it after the courtroom scene when her case against Max is dismissed, since the message was already clear, making the lengthy, didactic peroration unnecessary.

Gibson’s play offers no consolation. Women need to stand up to their manipulators, but how to do it? The sudden ending suggests there is no way out.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply