“It is unthinkable in progressive Canberra that a significant and identifiable group of residents has been left behind and feel totally alienated. What an outrageous suggestion!” say JON STANHOPE & KHALID AHMED.

In our last column we looked at whether it was “progressive” when a particular cohort of people in a community are knowingly left behind in terms of, say, their disposable income and their capacity to engage in the life of the community.

In other words, we questioned the true meaning of the term “progressive”.

We raised this issue in light of the so-called self-designated “progressive” policies of the ACT government. However, the US election was just days away when we wrote that article and its outcome is relevant to this discussion.

Much has been written about the US election and how was it that a misogynistic, racist, convicted felon prevailed over a public prosecutor? However, there is some consensus among thoughtful observers that alienation and a feeling of being ignored and disenfranchised played a significant part in the election result.

The swinging voters, relatively small in number but enough to make a difference in key counties and states, were from the minority groups traditionally aligned with the “progressive” Democrats. But to them, pleas about risks to democracy and the economy were irrelevant.

However, it is surely unthinkable in a progressive community such as Canberra, that a significant and identifiable group of residents has been left behind and feel abandoned and totally alienated.

What an outrageous suggestion! That would be contrary to our vision of ourselves as a caring and inclusive society. There is ample evidence that we put considerable stock in that identity. For example, we voted overwhelmingly in favour of a Voice to the Parliament, and we have “the most progressive government in Australia”. Just ask the Greens and Labor.

Julie Tongs, CEO of Winnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Health Corporation, recently commented on the racial prejudice experienced by Aboriginal people living in the ACT.

Ms Tongs has unquestionable credentials having led Winnunga Nimmityjah for more than three decades, and having had personal contact with thousands of Aboriginal residents of Canberra and the region.

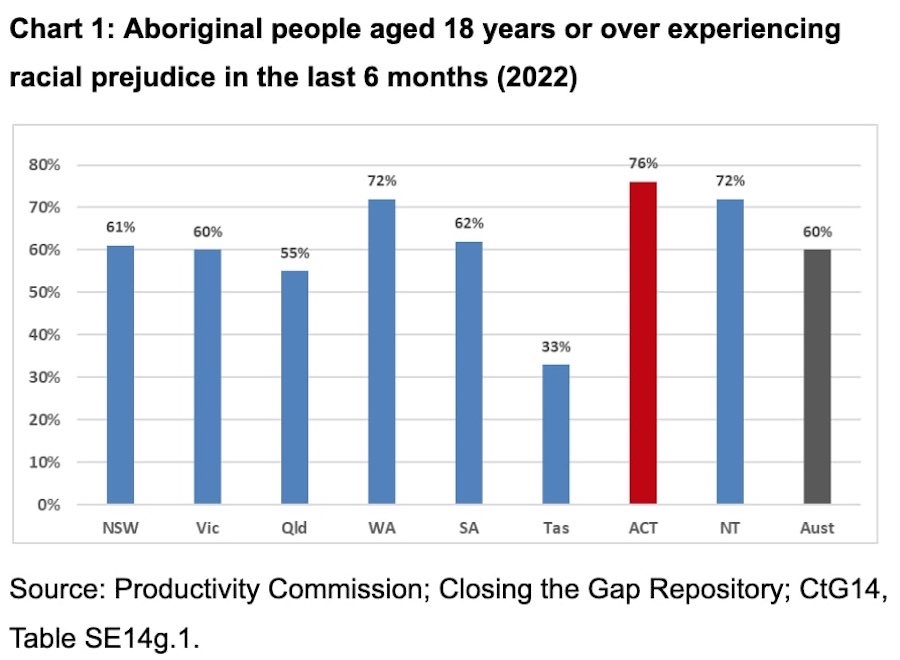

However, on this occasion she was referencing data published by the Productivity Commission in its most recent Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report, reproduced in Chart 1.

The chart reveals that Aboriginal people living in the ACT experience racial prejudice, ie racism, at the highest rate in Australia with more than three in four Aboriginal people (76 per cent) reporting such an experience in the past six months.

Based on this statistic, it is reasonable to conclude that almost every Aboriginal person in the ACT has experienced racial prejudice or vilification in their life.

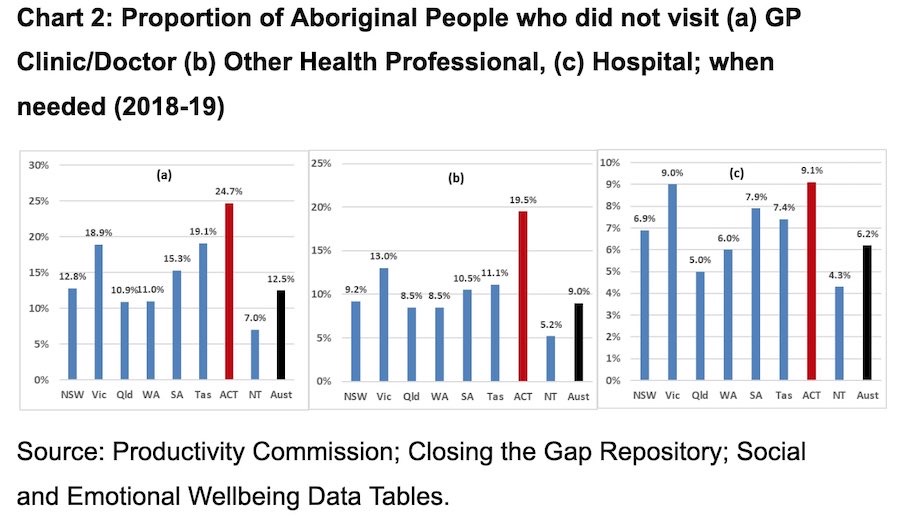

The Productivity Commission report also details access to a range of government services, including for example visits to a GP, other health professionals, and/or a hospital, when needed. Chart 2 reveals, for all states and territories, the proportion of Aboriginal people who did not visit a health professional or facility despite an obvious need to do so.

The ACT-specific data is as shocking as it is shameful. Around one in four (24.7 per cent) of Aboriginal people in the ACT did not visit a GP or a clinic when needed, which is double the national rate of one in eight (12.5 per cent), and the highest in Australia.

Around one in five (19.5 per cent) Aboriginal people in the ACT did not visit a health professional other than a GP when needed, which is more than double the national rate of one in 11 (9 per cent), and the highest in Australia.

Around one in 11 (9.1 per cent) Aboriginal people in the ACT did not visit a hospital when needed, which is one and a half times higher than the national rate 6.2 per cent, and the highest in Australia.

The Productivity Commission also reports on the reasons for not visiting, or what prevented the respondents from visiting, an appropriate health professional or hospital. The respondents were asked whether affordability, cultural safety, time and physical accessibility, or whether work or personal commitments were the reasons for not visiting.

In the ACT, more than a quarter of the respondents cited cultural safety (the highest rate in Australia) and more than a third stated time and physical accessibility (again, the highest rate in Australia) as the reasons for not going to hospital.

There is a very similar picture with cultural safety (one in four) and time and physical accessibility (almost half) for not visiting a GP, which are the highest rates for individual reasons. Unsurprisingly, affordability was cited as a significant factor in not visiting other health professionals.

That three out of four Aboriginal people living in Canberra have experienced racial prejudice would, one assumes, be of deep concern to a progressive minister for Aboriginal affairs. That up to one in four Aboriginal people living in Canberra do not visit a health professional or facility when needed would be of deep concern to a progressive minister for health.

In the ACT, both these portfolios were held until the October election by a single minister, Rachel Stephen-Smith. [Post election, the indigenous portfolio moved to Suzanne Orr]. We are not aware of any minister’s or the ACT government’s reaction or response to these damning statistics.

To be fair, it may be that the ACT’s mainstream media has simply deemed the issue as not warranting their attention.

Ms Tongs has, for several years, been urging the ACT government to initiate a Board of Inquiry (Royal Commission) into Aboriginal disadvantage and the lived experience of Aboriginal peoples living in Canberra.

As this latest report by the Productivity Commission reveals Aboriginal peoples in the ACT experience the worst outcomes across a whole spectrum of indicators, in all of Australia. Following the release of this most recent report of the Productivity Commission she has renewed her call for such an inquiry.

Julie Tongs’ advocacy for such an inquiry has fallen on deaf ears with the oh-so progressive Labor and Greens parties dismissing out of hand her calls for the need for an inquiry into these issues.

In a previous article, we highlighted some policy choices of the ACT government and asked whether they could in all honesty be called “progressive”.

Some would argue, as indeed we have seen, that while some policies pursued by the government may have been misguided, or necessary to continue in office, eg, the tram, but that the ACT government is nevertheless inclusive and progressive.

However, it’s indisputable that this latest report from the Productivity Commission on the ACT Labor/Greens response to the needs of the Canberra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community reveals that they are anything but progressive.

Jon Stanhope was ACT chief minister from 2001 to 2011 and the only chief minister to have governed with a majority in the Assembly.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

![For graphic designer Tracy Hall, street art is like any artwork, her canvas has been swapped out for fences and plywood, her medium changing from watercolours to spray paint.

A Canberra resident for 13 years, Tracy has been a street and mural artist for the past five.

Her first exploration into grand-scale painting was at the Point Hut toilets in Banks five years ago. “They had just finished doing up the playground area for all the little kids and the words [of graffiti] that were coming up weren’t family friendly,” she says.

“So I ended up drawing this design and I got approval for the artwork.”

Many of Tracy’s time-consuming artworks are free, with thousands of her own dollars put into paint.

@traceofcolourdesigns

To read all about Tracy's fabulous street art, visit our website at citynews.com.au or tap the link in our bio! 🎨🖌

#canberranews #citynews #localstories #canberrastories #Citynews #localnews #canberra #incrediblewomen #journalism #canberracitynews #storiesthatmatter #canberralocals #artist #streetart #streetartist #StreetArtMagic](https://scontent.cdninstagram.com/v/t39.30808-6/490887207_1225841146218103_6160376948971514278_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=yse5ujF1BOUQ7kNvwE8vMJJ&_nc_oc=AdmACWW3pCwuhoAJjTJgeYL0PrOjZetex1flAsV7seJ8OPT1_w_DCdBrY998OXsAdFw&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=M3Eat5CavCFLyQKem8wl7A&oh=00_AfEelLohW-0BM38EPlPqLO_ehfn2HbeGBZ7_42rmOJ7w8w&oe=68079794)

Leave a Reply