In the international art world, Gauguin is a box-office hit. How do galleries balance Gauguin commercial success with heightened public sensitivity to issues of gender, race and colonial appropriation, asks book reviewer COLIN STEELE.

Nicholas Thomas’ new book Gauguin and Polynesia, with 100 full-page colour illustrations, comes at a most appropriate time, given the current NGA Paul Gauguin exhibition, curated by Henri Loyrette, former president-director of the Musée du Louvre.

Loyrette has stated: “This is the first exhibition devoted to Gauguin and Oceania, a survey of his entire corpus as seen from his final destination, the Marquesas”. Polynesia was basically Gauguin’s home for the last 12 years of his life until his death in 1903.

Thomas reflects: “Major museums well aware that a Gauguin blockbuster will sell tickets as almost no other show can, try increasingly to have it both ways, vaunting the art, while inviting debate”.

In the international art world, Gauguin is a box-office hit with, at least, six exhibitions of his work in the last decade. How do galleries balance Gauguin commercial success with heightened public sensitivity to issues of gender, race and colonial appropriation?

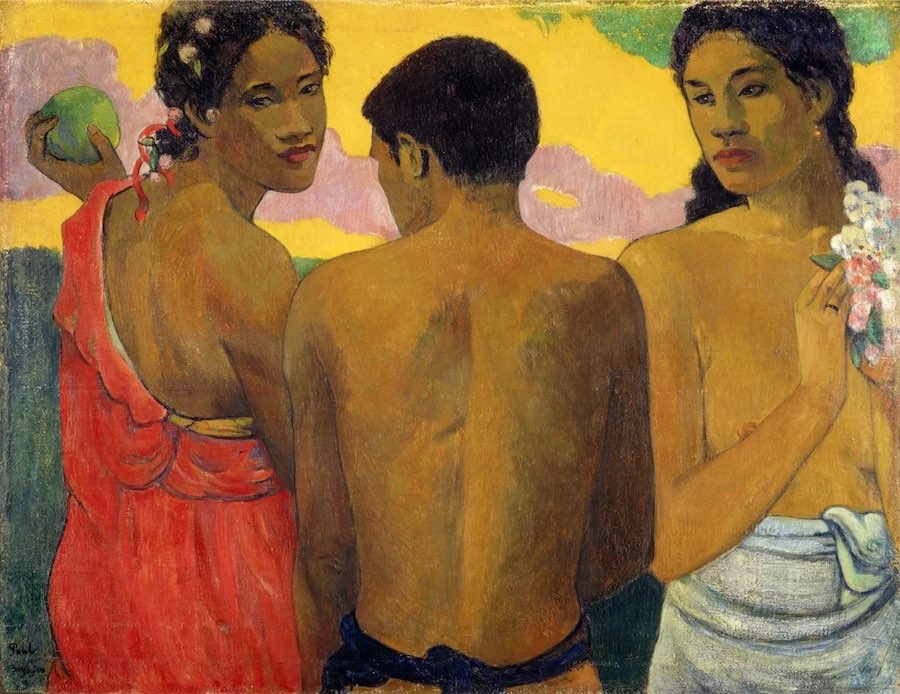

The pictures of Tahitian women set against exotic colourful locales have certainly established the Gauguin image. The first Gauguin souvenir postcards were sold in 1913 and today Gauguin posters abound and a major Polynesian luxury cruise ship is named after him.

Thomas, former ANU academic, now professor of historical anthropology at Cambridge University, contributed to the NGA exhibition catalogue as well as participating in a major seminar.

In his preface to Gauguin and Polynesia, Thomas, writes: “Gauguin has become one of the most popular of all modern artists, but also been regarded with deep ambivalence, and is now censured, seen as a sexual predator in life and a colonialist in his art, guilty on multiple counts of cultural appropriation.”

A previous Gauguin exhibition at the Courtauld Institute in London had stimulated a Times newspaper headline, “You can’t enjoy Gauguin without guilt”. New York art writer Meredith Mendelsohn wrote in 2017: “While there are plenty of white, male artists whose troubling lifestyles can be understood somewhat separately from their art, the difficulty with Gauguin is that his behaviour is laid bare on his canvases.”

Which leads directly to the question: does the character of an artist matter when we are looking at his/her work?

Thomas says that his book “is interested in rescuing the art from the artist and from the myths that he invented around the meanings and ambitions of his work” and “tries to offer another way of seeing Gauguin, beyond the standoff”, ie between opposing artistic and historical camps.

Dr Lucina Ward, NGA’s curator of international art, has said through “the lens of the 21st century, we may know him for the wrong reasons – and we’re completely acknowledging that, and facing up to that. There’s no point not talking about these things. [But] Gauguin is one of those artists in the 19th century, that if there were no Gauguin, 20th and 21st century art would be really, really different”.

NGA Director Nick Mitzevich has said that the NGA sees the exhibition “as an opportunity to connect artists across the Moana Pacific… and invite new perspectives to Gauguin’s life and legacy”.

Thomas, with more than 40 years of Oceania research, places Gauguin firmly in the framework of Polynesian history and culture, juxtaposing myth and colonial modernity.

Thomas is interested in “rescuing the art from the artist” and is “struck by a kind of disconnect between the image of Gauguin as an artist and the critical image of Gauguin that has become increasingly prominent in recent years”.

While Gauguin “was undoubtedly captive to stereotypes of the exotic and the primitive”, Thomas finds in many of his paintings a desire to engage with contemporary Tahitians.

Thomas examines Polynesian local beliefs, ceremonies, landscape and daily life in the context of Gauguin’s art and his legacy, placing the female dress and textiles that women wore in Gauguin’s paintings in a contemporary context rather than “a prelapsarian past”.

He reflects, however, “Gauguin‘s marital relationships with young Polynesian women were certainly troubling, although within the French legal marital limits of the time, the bigger problem is… that certainly later in life, he is carrying syphilis and passing that on”.

Thomas ultimately neither celebrates nor condemns, noting that Gauguin’s work “is in the end somehow affirming, or irretrievably pernicious, is beyond resolution”.

Thomas delivers a meticulously researched, fresh perspective on Gauguin’s life and art within the Polynesian framework.

Gauguin’s largest surviving painting and self-described masterpiece, ”Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” is perhaps ultimately the key reflection from Gauguin and Polynesia.

Gauguin and Polynesia. By Nicholas Thomas. Head of Zeus. $79 99.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply