THE latest plan to link Sydney and Melbourne with a very fast train might sound far-fetched – and even a little wacky – but it’s nowhere near as silly as the first idea, nearly 200 years ago, to forge a passage between Sydney and Bass Strait by the then NSW Governor, Sir Thomas Brisbane.

Brisbane’s idea was to select a band of convicts from Sydney Cove, sail them to Australia’s southern coast and promise that if they made it back through the totally unknown country they’d be granted their freedom. It was fairly typical of Brisbane who spent six days out of every week plotting the stars of the southern hemisphere through his telescope at Parramatta and only one – Tuesday – running the colony.

When he confided his madcap scheme to Alexander Berry, a former ship’s surgeon turned colonial pioneer, Berry suggested a slight “amendment”.

He had been the beneficiary of the most daring and respected young bushman in the colony. Indeed, he’d become firm friends with the young man who had led him to some of the finest country in the Illawarra. Now, he told Brisbane, he had just the person to lead such an expedition. His name was Hamilton Hume.

When invited, Hume made another “amendment” – he set out from the outskirts of Sydney and through leadership, courage and bushmanship conquered the wild rivers, precipitous peaks and almost impassable scrubland to Port Phillip and returned without losing a man.

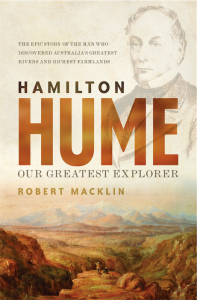

I learned this odd story two years ago when I began the research and writing of my book, to be launched next month by Professor Bill Gammage, “Hamilton Hume – Our Greatest Explorer”.

It is the first biography of the great man to find a commercial publisher and that reflects another oddity: in our schools and universities we have never been taught Australian history; instead we’ve learned the British history of Australia, a very different beast. And because Hume was the only Australian-born of our explorers, his remarkable achievements have never been properly recognised.

Even the great expedition of 1824-25 that flowed from Alexander Berry’s intervention has been portrayed as a joint operation of Hume and the British-born William Hilton Hovell; whereas the truth is that on three occasions a fearful Hovell demanded that they turn back and on two of them he tried to rouse their six convict companions to mutiny.

For many years Hovell and his friends among the “stirling” community promoted the canard that the “currency” lad, Hume, merely accompanied the former ship’s captain in the triumphant journey there and back.

It was not until Hovell made the mistake of giving a speech in Geelong in 1853 in which he claimed the leadership for himself that Hume finally responded – with chapter and verse from the other members of the expedition – and the truth was revealed.

But by then the myths had taken root and Hume unwittingly had become a victim of the so-called “culture wars” that still bedevil our history today. It didn’t help his cause that Hume was unique among the explorers in his friendship and respect for the Aboriginal people through whose country he travelled. Indeed, it was Hume’s early friendship with surveyor-general Thomas Mitchell that led Mitchell to order his surveyors to seek the Aboriginal names for the geographical features they discovered. And it was Hume’s “friends of the forest” who gave safe passage to the expedition he led with Charles Sturt to discover the Darling in 1828.

However, in another oddity, mine is not the first “life” of Hume. That honour goes to R.H. Webster, the first director of L.J. Hooker in the ACT, “the man who auctioned Canberra” in the 1960s.

Bob Webster was my father-in-law and though his “Currency Lad” did not find a commercial publisher, it was privately published by the family in 1982 and formed the hard kernel upon which my work was built.

Bob Webster was my father-in-law and though his “Currency Lad” did not find a commercial publisher, it was privately published by the family in 1982 and formed the hard kernel upon which my work was built.

But since Hamilton Hume’s life covered the first 80 years of British conquest and settlement, it allowed me to expand the story to that pivotal period of transition of Australia from penal colony to the beginnings of nationhood.

It is an amazing time of frontier wars, of transportation replaced by the bonanza of gold, the bushranger rebellion and the quest for federation. But none of that extraordinary transformation could have occurred without Hume’s discovery of the magnificent stretch of country – now traversed by the Hume Highway – “capable of producing food to feed half the world, wool to clothe half the world and gold to buy half the world” on his journey to Port Phillip (which the navigator Hovell insisted was Western Port).

Well may Malcolm Turnbull say that today “there has never been a more exciting time to be an Australian”. I challenge him to repeat it after he reads “Hamilton Hume – Our Greatest Explorer” (Hachette Australia, rrp $32.99).

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply