FIFTY years ago government censorship in Australia saw authors arrested, books banned and bookstore owners threatened by police, until one book changed everything.

Philip Roth’s “Portnoy’s Complaint”, a book “technically about masturbation”, according to Canberra author Dr Patrick Mullins, was chosen by publisher Penguin to challenge literary censorship in Australia, and eventually played a large role in bringing it to an end.

But before it did, the circulation of the book in Australia in 1970 led to criminal charges, police raids and a series of court trials across the nation.

Intrigued by these trials, Patrick began looking into court transcripts, which are scattered around the nation, to understand how Penguin, writers, booksellers, academics and lawyers reshaped Australian literature and culture forever.

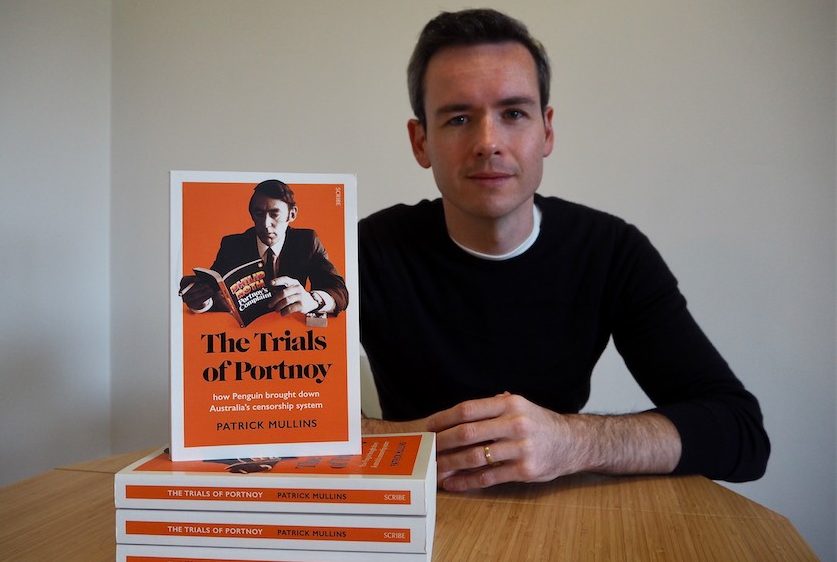

Patrick’s interest led to him writing “The Trials of Portnoy”, a book about the trials, literary censorship and “fighting for freedom”.

Now, published by Scribe, Patrick, 32, of Griffith, tells the story of “Portnoy’s Complaint” and its role in this fight for freedom.

“The book, [“Portnoy’s Complaint”], had been a bestseller overseas [after it was published in America in early 1969], but when it was banned Penguin Books secretly decided to smuggle it into Australia, print 75,000 copies, and then publish it all around the country,” he says.

“The book sold out within a fortnight, with people stampeding bookstores to get it.”

It was a big deal, according to Patrick, who says selling 10,000 in a year (at that time) was enough to make a book a bestseller.

“Then, the police swooped and there was a series of court trials in nearly every state over the book,” he says.

Here in Canberra, legendary bookstore owner Teki Dalton sold about 30 copies of “Portnoy’s Complaint” in his Civic-based shop before police officers threatened to prosecute him, if he continued to sell the book.

“He pulled the book from sale,” Patrick says.

“The book technically wasn’t even banned in Canberra but police still threatened to take him to court.

“Basically, they said, we’re going to make him lose time and money by dragging him through court. It was intimidation.”

ANU students at the campus newspaper, “Woroni”, had a bit more success, and Patrick says they printed an excerpt of the book in their orientation week issue.

“’Woroni’ said: ‘We’re printing this excerpt and we want to stir up controversy about censorship,” he says.

If people read the excerpt and wanted to buy the book, Patrick says “Woroni” had about 100 books, which they strategically marked up in price in case they needed to use the money for court fees.

But by that time (March, 1971) there had been three trials with mixed results, so the Woroni editors escaped charges because of the uncertainty around the differing results.

Patrick says censorship not only affected literature, but it also affected other areas such as arts and theatre, too. But it was literature that made the big push, which gave many industries more freedom.

“Censorship… kept all sorts of books away from Australian readers,” Patrick says.

“‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, ‘A Farewell to Arms’, ‘Lolita’, ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, ‘The Catcher in the Rye’, among others, were banned on grounds that they were obscene, or indecent, or blasphemous, or seditious.

“The federal government kept those books out of Australia, and the state governments prosecuted Australian writers, publishers, and booksellers who produced or sold obscene or indecent works.

“The big [punishment] was jail. [Australian author] Robert Close was jailed in 1946 for writing a book called ‘Love Me Sailor’.”

According to Patrick, Robert did three months in jail for using the word “rutting” in the book.

“One of the reasons ‘Portnoy’s Complaint’ was chosen was because of the taboo subject matter,” Patrick says.

At the time, Patrick says masturbation was something that people were made to feel ashamed about.

“This is an example of how literature can teach you not to feel ashamed and not to feel guilty,” says Patrick, who believes literature is also a way of developing empathy.

“Even if you don’t like books like that, you can understand they’re exploring human behaviour and allowing us to understand different points of view and ways of living. Literature can change and shape our lives.”

Before the end of censorship, Patrick says university students would have to go overseas, get copies of books there, read them there and then come back to Australia.

Now, Patrick wants his book to highlight the brave people who forced these changes.

“We forget too easily the people who make change in Australia,” he says.

“I want people to remember these brave people, both at Penguin, and the people who testified in the trials.”

All up, Patrick says there were eight trials all around Australia about the selling of the book, with a mixture of guilty verdicts, collapsed cases and trials where they couldn’t reach a verdict.

“The results of those trials were mixed — and eventually both the federal and state governments had to back down and remove ‘Portnoy’s Complaint’ from the banned list,” he says.

“It helped bring down the censorship system, which was dismantled in 1972, when Gough Whitlam was elected.”

“The Trials of Portnoy” ($35) via scribepublications.com.au

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply