ONCE upon a time, if you wanted a beer you went to Queanbeyan, simple. Thanks to King O’Malley, the federal Minister for Home Affairs of the day, Canberra was a dry town from 1911 to 1929.

O’Malley, a fierce teetotaller, who called grog “stagger-juice” and abstained from it, persuaded his cabinet colleagues to ban, in 1911, the granting of liquor licences in the Federal Capital Territory.

Queanbeyan resident Phill Hawke, who is researching O’Malley’s “flamboyant” life, says that at the time it wasn’t illegal to possess or drink alcohol in the ACT, you just couldn’t sell it.

“So, most would head to Queanbeyan, fill their boots with grog, come back and drink it,” says Hawke.

“It is believed that around 70,000 bottles were collected as rubbish in the first six months of 1926.”

The five established pubs in Queanbeyan were swamped by Canberra drinkers, particularly on the weekends.

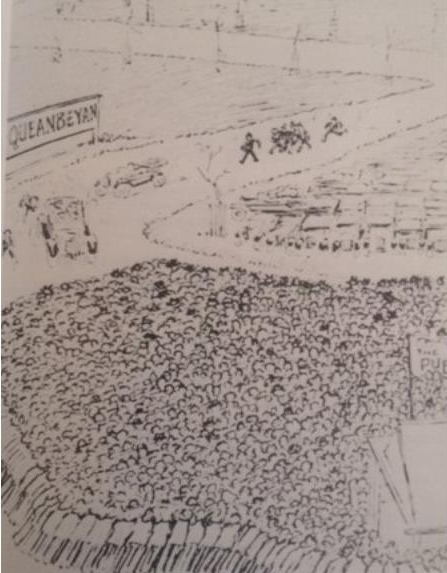

One famous cartoon showed Parliament House deserted, with thousands heading to Queanbeyan.

“The road to Queanbeyan was called the ‘road to ruin’,” Hawke says.

“People walked the seven miles [11 kilometres] from Canberra to Queanbeyan and back, just for their grog… with cars, taxis and people on horseback all clogging the road.”

A “colourful” character who claimed he was American and then later a Canadian so he could qualify for election, O’Malley worked as an insurance salesman before entering politics.

“In both professions making use of his knack for oratory and publicity stunts,” says Hawke.

Famous for his flashy dressing and his radical ideas of democracy, he is remembered for his role in the development of the national capital as well as his advocacy for the creation of a national bank.

Thanks to his American background, he was also responsible for the spelling of “Labor” in Australian Labor Party.

But his unpopular ban on alcohol in the ACT was perhaps his most known legacy.

O’Malley’s “stagger-juice” circular, projecting his views to his Home Affairs Department of?cers, is an interesting document.

It says: “Stagger juice and official business are absolutely incompatible… There can be no efficiency without speed, and speed is impossible with muddled whisky brains.”

From 1927 MPs and their staff were able to enjoy the bar at Parliament House, but anyone else who wanted a drink had to make the trek across the border to Queanbeyan.

“Apparently, motor cars were employed to carry liquor into Canberra from Queanbeyan and that a service of buses was run to take workmen from Canberra to Queanbeyan so that the town was converted into a Saturnalia [an ancient Roman festival of Saturn in December, which was a period of merrymaking] every weekend,” says Hawke.

As a result, the hotels of Queanbeyan did a thriving trade for many years.

It’s not the first time Canberrans have crossed the border in search of prohibited activity.

In 1956, Queanbeyan roads were choked with Canberrans again, with the introduction of poker machines in NSW.

“Poker machines were not introduced in the ACT until 1977 and so another influx of people came across the border,” Hawke says.

And in 2020, Canberrans prevented from playing pokies due to coronavirus restrictions were crossing the border into NSW.

“Funny how history has a habit of repeating itself,” Hawke says.

As Canberra grew and more public servants took up residence, O’Malley’s ban on liquor sales came under pressure.

In January 1928, “The Canberra Times” reported that drinkers in the territory were resorting to drinking tonic wine obtained from chemists.

“They certainly were obtaining grog on the sly,” says Hawke.

“The ‘Braidwood Dispatch’ reported in February 1926 a case where three men faced the Queanbeyan Police Court charged with selling liquor without a licence, they were each fined 30 pounds or three months in jail.

“It was stated in court that a car carrying the sly grog arrived at Red Hill and a Constable Foster pretending to be intoxicated gave the sellers 15 shillings for five bottles.”

In 1928, the government led by Prime Minister Stanley Bruce held a plebiscite and O’Malley’s 1911 ban was overturned.

Premises were leased at Civic, Kingston and at Manuka to operate as cafes along the continental style of having drinks at tables.

In 1935 two of the cafe licences were sold and the purchaser of the Kingston licence built the Kingston Hotel, the first traditional-type hotel in Canberra.

In the end, O’Malley’s wish that the territory “shall be dry” was not achieved.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply