Christian Porter’s funding from a “blind trust” is an integrity test for the Prime Minister, writes political columnist MICHELLE GRATTAN.

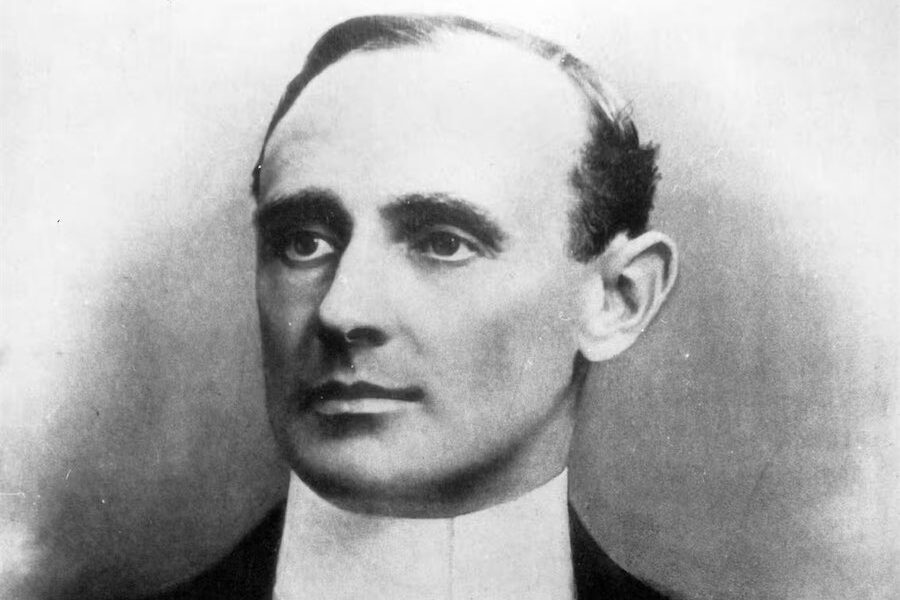

FOR a very intellectually smart man, Christian Porter often shows extraordinarily bad judgment.

After he was accused of historical rape, which he strongly denied, he believed he could remain as attorney-general, despite that being clearly not viable.

Then he chose to sue the ABC and one of its reporters for defamation, but quickly found this brought reputational risks and huge financial costs. The case was settled before going to trial.

Now Porter has disclosed, in an update this week to the parliamentary register of MPs’ interests, that he has accepted funds from a “blind trust” to help him pay his legal bills.

Unsurprisingly, there was a general outcry, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison has his department advising whether this arrangement breaches the ministerial standards code. Once more, Porter’s frontbench future is hanging in the balance.

How this plays out is an integrity test for Morrison. Porter needs to leave the ministry or (taking the most lenient view of the situation) immediately have the trust repay all the money to those anonymous benefactors.

Indeed, Porter shouldn’t have to wait to be told by the PM – he should recognise this himself.

Regardless of the departmental advice to Morrison, acceptance of anonymous donations fails the standards of propriety that we should expect from MPs, and certainly from ministers.

Former PM Malcolm Turnbull – who admittedly is no fan of Porter for various reasons – described his action colourfully as “like saying ‘my legal fees were paid by a guy in a mask who dropped off a chaff bag full of cash’”.

Porter argued the government didn’t pay for his court action so these funds are coming to him in a private capacity. But regardless of the fact he was liable for his bills, he is a senior public figure – the debate surrounded his public role and anyway the “private” morphs into the “public”.

There are practical reasons, as well as the matter of principle, why political figures shouldn’t accept money from unknown sources.

While Porter says he doesn’t know the names of the donors, obviously others do. Potential benefactors must have been directed to the trust, which has administrators, with the funds provided to Porter’s lawyers.

Why do the benefactors want to remain anonymous? Do they believe backing Porter will cause them damage or embarrassment? These donors have helped Porter with money, but by staying in the shadows they have actually harmed him, as his present invidious position shows.

One day, their names may emerge publicly. If they don’t, they very likely will be known privately in Liberal circles. That just invites rumours, down the track, that so-and-so might have obtained favours from the Liberals because he or she helped Porter out. Compromising all round.

The rules covering the disclosure of political donations are woefully inadequate. Among much else, we can now see they should extend to cover donations made to politicians in their so-called “private” capacity.

The anonymous largesse to Porter is the latest example of the poor standards in political life that so alienate many of the public, fuelling distrust and cynicism.

At a governmental level, we’ve seen this in the scandals of the community sports grants and commuter car parks schemes before the last election, which were run essentially as vote-buying exercises. Proper process came a distant second to the pursuit of political advantage.

In the sport rorts affair one minister, the Nationals’ Bridget McKenzie, was finally forced to resign. But the reason given was a technicality; there was no admission by Morrison that the scheme – in which his office was intimately involved – had been shamelessly rorted. (All’s ended well for McKenzie – after the Barnaby Joyce leadership coup she was restored to the cabinet.)

Constitutional lawyer Anne Twomey, from the University of Sydney, in a recent speech pointed to the damage this sort of behaviour does.

“The notion abounds amongst politicians that the means are justified by the ends – that it is OK to abuse the rule of law and make unlawful grants to buy an election outcome, because the success of your side in that election is for the overall benefit of the country,” Twomey said.

“Even if that were objectively true in the short term, it is not in the long term. The corrosion of the rule of law and the seeding of future corruption are profoundly worrying. We are being set on a trajectory with horrific ends. Yet our own leaders cannot see beyond the immediate glittering prize of the next election.”

The “whatever it takes” mindset has become all-pervasive. It’s often partnered with “whatever can be hidden”.

The Morrison government is notorious for trying to conceal its workings. At present it is attempting to legislate to get round a legal judgment that found the national cabinet is not a committee of the federal cabinet and therefore it cannot claim cabinet confidentiality. Let’s hope the Senate crossbench stands up against the government’s bid.

A few years ago, both sides of federal politics doubted the need for a national commission against corruption. But after Labor, the Greens and crossbenchers pressed the issue, the Coalition government was reluctantly forced to accept the idea.

While attorney-general, Porter produced draft legislation in late 2020 for an integrity commission. His model was widely criticised; its many holes included that there would be no opportunity for whistle-blowers to directly lodge complaints against politicians and public servants, and investigations involving these figures would not have public hearings.

The government says it will introduce its legislation for the integrity commission before year’s end. We don’t know what changes it is making to the earlier version following the consultation process, but whatever the revised model looks like, it will be a stretch to get legislation through before the election.

An integrity commission is an overdue reform that will help promote greater trust in the political system. Australia Institute polling done in August in four seats – Brisbane (Qld), Braddon (Tas), Bennelong (NSW) and Boothby (SA) – found overwhelming support for setting up a commission. But it’s only part of the answer to the trust deficit.

To promote trust, politicians and governments need to feel proper standards matter – that there is a political cost (short of an integrity commission investigation) to doing the wrong thing, or cutting corners for political ends.

Reinforcing this point requires deterrents to bad behaviour in the form of institutional checks and transparency as well as sanctions.

But there also needs to be positive reinforcement wherever possible – within parties, inside a government, and from voters – of the message that high standards are a central KPI for politicians.

Without that messaging, lack of trust and public cynicism will only grow, poisoning the political system further.

Michelle Grattan is a professorial fellow at the University of Canberra. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply