“When the Nazis in November 1938 attacked Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues on ‘Kristallnacht’, the night of broken glass that signalled the start of the horror, Australian officialdom was silent,” writes “The Gadfly” columnist ROBERT MACKLIN.

THE announcement that Canberra is to have its own Holocaust Museum raises some fundamental questions about Australia’s own Aboriginal history.

“Holocaust” is now a label reserved for the barbarity that Adolf Hitler and his accomplices visited upon Europe’s Jewish people in World War II. It was made the more shocking by its concentration over half a decade in the obscenity of Auschwitz and the other death factories.

Yet the fate of Australia’s Aboriginal people differs only in the period and the location of its execution. It took much longer, and its settings were scattered over a continent bigger than Europe. Its instruments were diverse – guns, poison, dispossession, degradation and disease.

The result was the same.

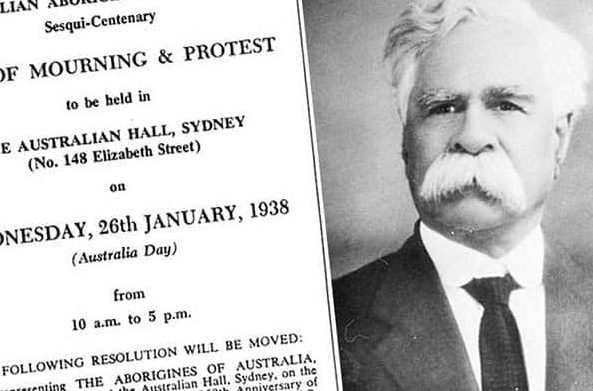

There is a singular connection: when the Nazis in November 1938 attacked Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues on “Kristallnacht”, the night of broken glass that signalled the start of the horror, Australian officialdom was silent. But William Cooper, a Yorta Yorta man from the Murray Valley, leader of the Australian Aborigines League, took a letter of protest and condemnation to the German Consulate in Melbourne.

They refused to receive it.

There is also a disconnect: in the wake of the Nazi atrocity, the Germans of a new generation had the courage to own the actions of their forebears, to confess and crave forgiveness, to pay reparations of the exchequer and the spirit. Not so the Australian colonisers.

However, behind the scenes a Jewish Rabbi, Avraham Schwarz has made it his life’s work to educate Australia’s Jewish community about William Cooper and indigenous issues since the 1990s.

He established the with Cooper’s oldest surviving grandchild, “Uncle” Boydie Turner. He persuaded Angela Merkel to accept William’s 1938 protest in 1983. And the new Holocaust Museum in Perth will feature a huge image of William Cooper on its façade.

Yet as the centuries pass, the Aboriginal people are still waiting for Australian governments to emulate the German response. Along the way, a cohort of Australians, black and white, have raised their hands and their voices to officialdom, arguing, pleading and demanding the natural justice that we codify in our unofficial national canon as the “fair go”.

The latest cry for justice, the Uluru Statement from the Heart, is the most powerful yet articulated. It resounds from an Aboriginal gathering – the aroused and re-energised survivors of their holocaust – demanding a voice in policies affecting the land their ancestors tended for 60,000 years; a truth-telling of the realities of the occupiers’ attempted ethnocide; and a treaty that lays down the conditions for a future that will finally “close the gap” in status, wealth and power between themselves and the colonisers of 1788.

The response of successive Australian governments has been either symbolic – Paul Keating’s Redfern Speech and Kevin Rudd’s apology to the stolen generations – or niggardly. “Closing the gap” between the original Australians and the health and wealth of their white compatriots began as an aspiration; it remains as a plaintive echo of systemic failure.

Perhaps Canberra’s Holocaust Museum will play a part in turning the national tide. William Cooper’s long journey to the German Consulate would not have been in vain.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply