Political commentator MICHELLE GRATTAN says federal opposition leader Anthony Albanese has diminished his party’s credibility by failing to act after shock revelations of branch stacking from this week’s hearings of the Victorian Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission.

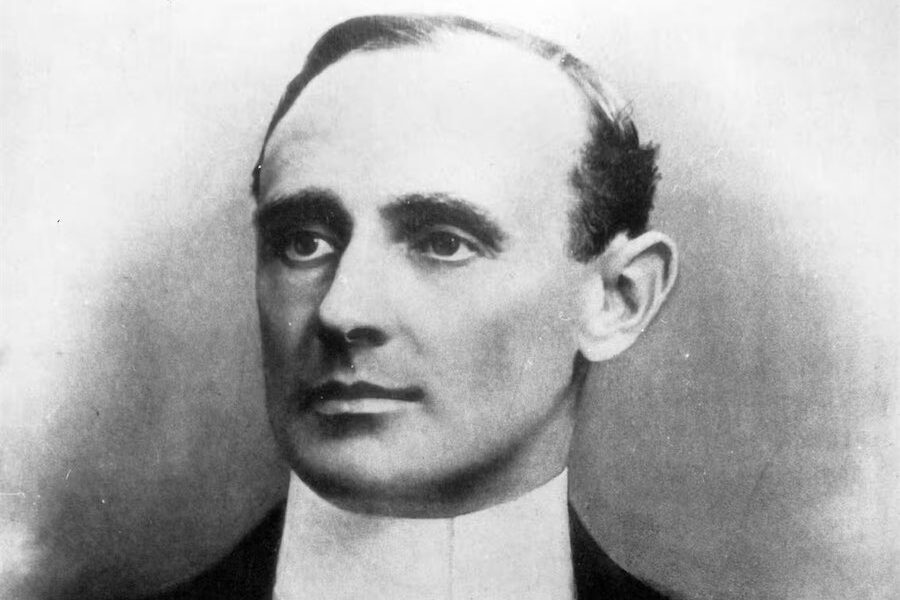

ANTHONY Albanese has diminished his own, and Labor’s, credibility on integrity issues by declining to act immediately against MP Anthony Byrne, who this week admitted to participating extensively in branch stacking.

Byrne’s evidence to Victoria’s Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission was horrifying for anyone concerned with how our democracy works. The issues raised go far beyond the particular circumstances.

The IBAC investigation into branch stacking in Victorian Labor was triggered by Nine’s 2020 revelations about the activities of Adem Somyurek, at the time a factional power broker in a subgroup of the right and a minister in the Andrews government.

The average person might ask, what is “branch stacking” anyway? Isn’t it just one of those dark arts practised in all parties? Does it amount to much to be worried about?

“Branch stacking” comes in more than one variety.

For example, a political aspirant wanting to win a preselection ballot might go on a recruiting drive to sign up friends and supporters to join his or her party.

This is reasonable enough, provided the people pay their own memberships, understand what they are joining, and party rules specify a set time before they can vote (to stop a last-minute stack).

Some fringe religious groups organise “stacks”, which are more concerning, because of the potential influence on preselections and, indirectly, policy. Parties need to watch this, with rules about mass entries, although if the new members meet the proper requirements, little more can be done about it.

The branch stacking in which Byrne engaged is the corrupt industrial-scale activity for which the Victorian ALP has been notorious over decades. It amounts to a chronic disease.

Byrne and others paid the membership fees of people (“stackees” are mostly from ethnic communities) who were just numbers for Somyurek and the faction, doing what they were told (or being chased up if they didn’t).

Byrne admitted he even agreed to employ a couple of staff who just undertook factional work, and indeed didn’t turn up in the office at all (despite being paid by the taxpayer).

There are deeply disturbing consequences of having a party “stacked” with what are, in essence, phoney members who hand over their party ballot papers to factional chiefs or blindly mark them as ordered.

It’s a means by which corrupt factional chiefs can control who gets elected to the party’s conferences and committees, and who gets preselection. The factional heavies can also potentially exercise malevolent power over MPs.

Byrne was aware of what was good, or potentially bad, for his political career. He went along with the staff arrangement because to do otherwise “would not have been healthy for my long-term future”, he said.

More broadly, the branch-stacking issue goes indirectly to how Labor chooses leaders.

The ALP rank and file have a 50 per cent say in the election of the federal leader. But given that relatively few people (and many of them zealots) want to join political parties and the perennial difficulty of preventing branch stacking, the wisdom of according party members this degree of power – in the name of “democracy” – may be questionable.

Factions have become endemic in modern parties. Their presence is not all bad. Indeed, they can sometimes be useful for getting positive things done (as they were during the Hawke government).

But they have become too stifling, even when their wranglers are perfectly respectable. They narrow the gene pool of parliamentary candidates, leading to former political staffers and the like being over-represented in parliament, and the tight control they exercise puts off many people who’d make good MPs.

When faction chiefs are corrupt, with their power built on corrupt practices and the ability to press MPs, by implied threats, into participating in such activities as branch stacking, the parliamentary system is debased.

The position of Byrne, who has been in federal parliament since 1999, is complicated, given he’s admitted to misbehaviour but also called it out publicly.

Byrne has never been a high flyer but has won respect, including from the Liberals, for his measured role on the parliamentary committee on intelligence and security. On Thursday he resigned from that committee, of which he was deputy chair.

Within the factional play in Victorian Labor, he was hand-in-glove with Somyurek for many years – even if, as he indicated, he felt uncomfortable and somewhat compromised – until they fell out in recent times and he turned whistle blower.

Footage shot in his office led to the expose by Nine. After Byrne’s IBAC evidence this week Commissioner Robert Redlich commended him for the assistance he’d given the commission.

Byrne had, Redlich said, provided a great deal of evidence “against your interests. You have acknowledged wrongdoing, you have acknowledged breaches of a range of party rules.”

As whistle blower, it might be argued Byrne should not pay a penalty. But allowing that latitude would send the wrong message – to the Labor Party, MPs and the public. The correct message is that a member of parliament, and anyone who aspires to parliament, should stand up to corrupt pressures from the get-go.

Albanese is campaigning relentlessly against the government on a range of integrity issues. He’s attacked Liberal branch stacking. For him not to act decisively against Byrne smacks of double standards and a failure of leadership.

He has played for time in the Byrne affair, although he has shortened the time frame. Initially he said he wouldn’t pre-empt the IBAC processes. On Thursday he said “we’ll wait while the hearings are going on”.

Albanese has also pointed to what he did when the Somyurek scandal broke into public view. After the initial revelations, he (and Premier Dan Andrews) secured federal intervention in the Victorian ALP. Administrators are still in place and federal candidates – including Byrne – have been endorsed under this arrangement.

But Albanese’s arguments don’t cut it as a defence for his reluctance to act immediately on Byrne.

It’s no good his saying he has moved against corruption in Victoria if the subsequent, presumably clean, process has re-endorsed an MP with Byrne’s self-admitted record of misbehaviour.

It’s also unacceptable – and politically counterproductive – for Albanese to delay his judgment on Byrne. The MP’s confessions were cut and dried.

After this week’s evidence Albanese should have had Byrne’s endorsement for the 2022 election withdrawn. Indeed, he should have gone further and insisted he go to the crossbench.

The signals suggest Byrne will at some stage declare he won’t run for another term. He said in evidence he’d previously thought of retiring last time round but was prevailed on to stay.

If Byrne announces his retirement, or Albanese finally takes some stand, it will be too late for the Labor leader to claim moral authority. Time will have watered down the message.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra. This article is republished from The Conversation

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply