“The ACT juvenile suicide rate was below the national average in the period 2013-17, but in the last five years has increased to the second highest in Australia.” JON STANHOPE & KHALID AHMED expose the ACT government’s neglect of mental health.

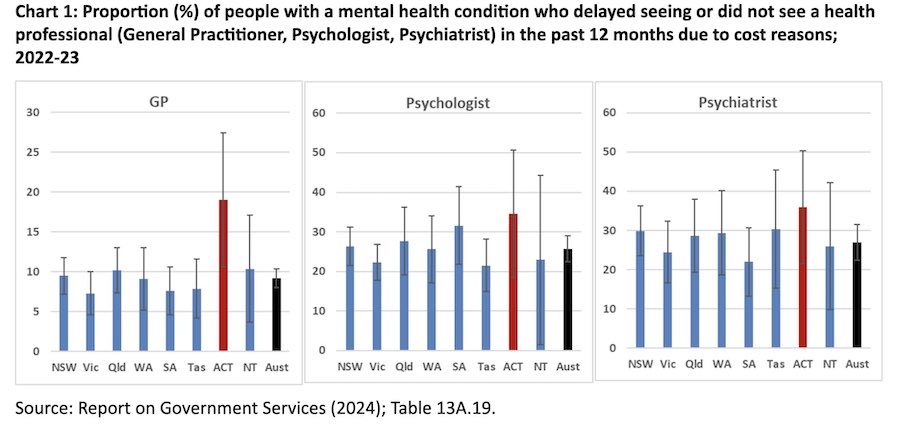

In which Australian jurisdiction are people with a mental health condition most likely to not see a health professional for reasons of cost?

The answer is the ACT.

In this column we raise sensitive and distressing issues.

In the past, we’ve highlighted the deterioration in the ACT’s performance or outcomes, on a range of economic, social and service delivery measures compared to other jurisdictions.

Perhaps the most confronting point of reference is the inequity within the Canberra community, raising moral questions about how we treat fellow Canberrans who are vulnerable and marginalised.

Our approach to these issues is evidence based and data driven, and our intent is to identify and highlight that which is out of the ordinary, should be questioned, and/or should not be accepted.

The same goes for the explanations, excuses, spin, misdirection and outright falsehoods of those seeking to defend or justify disparate outcomes in service delivery.

The issues we raise can be confronting, particularly in a “tribal” political environment, in which we are loath to accept that those with whom we associate, or support politically can do any wrong, and that anyone else is ever right.

However, our concern is for those Canberra residents who have suffered and continue to suffer through poor service delivery and neglect. We are also concerned that across a range of issues there is little or no reason to be confident that change for the better is either guaranteed or being actively pursued.

That brings us to mental health and why people in the ACT are most likely to not see a health professional for reasons of cost. The data in Chart 1 is drawn from a 2024 Productivity Commission Report and draws on an Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) survey.

It reveals that Canberrans with a mental health condition are twice more likely than the national average (the highest rate in Australia) to not see a GP, 35 per cent more likely to not see a psychologist (the highest rate in Australia) and 33 per cent more likely (the highest in Australia) to not see a psychiatrist, because of the cost.

With the ACT having the highest average incomes in Australia, these results are both unexpected and counterintuitive.

It is possible that, because of the relatively higher socio-economic status of Canberrans, as measured by average incomes and education levels, they are more aware of their mental health status. However, the self-reported incidence rates do not suggest the existence of any such disparity.

This was not the first or the only survey that has identified a sensitivity within ACT households to out-of-pocket costs for health care. The higher average incomes compared to the national average mask a relatively higher incidence of financial stress, and inability of ACT households in the bottom two income quintiles to raise short-term funds was incidentally reported in the 2012 taxation review.

In addition, the ACT has a relatively higher proportion of households with a mortgage, which coupled with higher dwelling prices and rents, has resulted in financial stress in the ACT being relatively greater.

To make matters worse there has been a severe shortage of mental health professionals with some closing their books. While the shortage is nationwide, the situation in the ACT is among the worst.

Alarmingly, as reported in CityNews in 2021, Dr Fatma Lowden, then chair of the ACT branch of The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, pointed out the relationship between an increased risk of self-harm in the ACT and the under supply of mental health professionals. She pointed to a high risk of self-harm in a particular risk group.

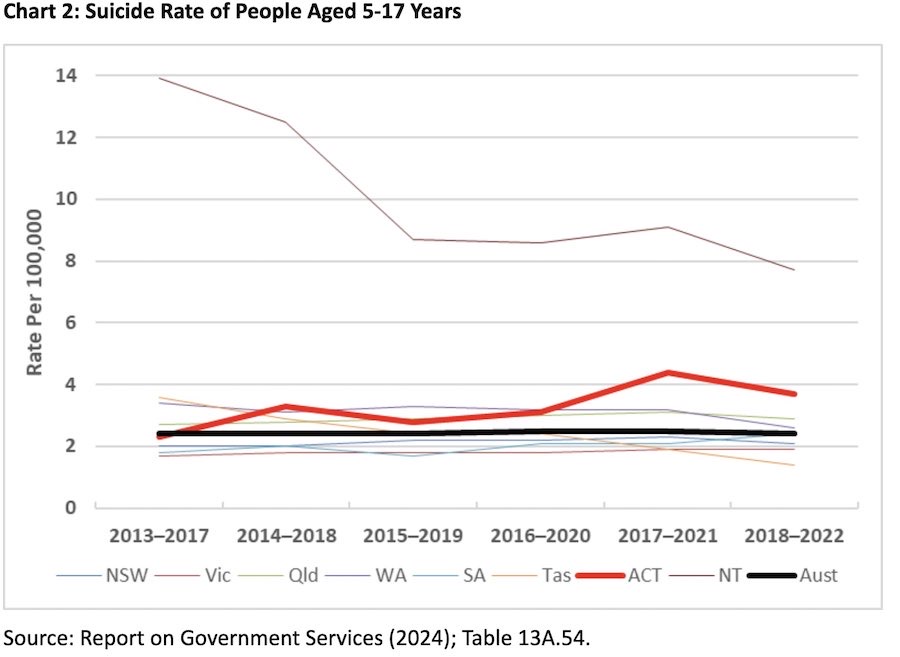

Distressingly, the data published by the Productivity Commission in its 2024 report confirms Dr Lowden’s expressed concerns. Overall, the suicide rate in the ACT has trended upwards since 2013, when it was 14 per cent below the national average, to being close to the national average in 2022. Most disturbing is the trend increase in the suicide rate of Canberrans aged 5-17 years.

Chart 2 reflects the rolling four-year average rate of juvenile suicide from 2013-17 to 2018-22 for all Australian jurisdictions.

The suicide rate of young people in the NT is a national shame, although it has reduced markedly in recent years. The ACT juvenile suicide rate was below the national average in the period 2013-17, but in the last five years has increased to the second highest in Australia behind the NT. The national average has remained unchanged.

Dr Lowden stressed the importance of the community mental health systems working optimally and identified a lack of funding as a primary reason for the “dilapidated” state of community health services in the ACT.

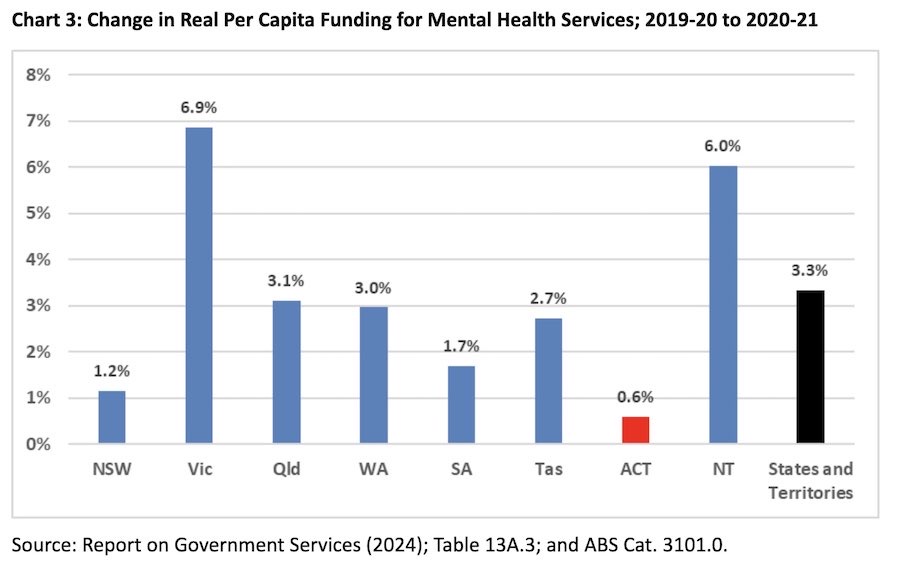

The expenditure data for the ACT for 2021-22 is not available, as the territory was apparently unable to provide the information to the Productivity Commission. The increase in ACT government expenditure on mental health services from 2019-20 to 2020-21 was 2.3 per cent against a national average increase of 3.8 per cent, and was the second lowest in Australia. Per capita funding in the ACT, ie, once adjusted for changes in population, was the lowest of all states and territories (Chart 3).

It is important to clarify two points to ensure that any discussion is not misdirected.

The ACT’s per capita expenditure is relatively higher than the national average. That is to be expected, given its diseconomies of administrative scale, which are recognised by the Commonwealth Grants Commission and compensated for in the GST distribution.

The data presented relates to states’ and territories’ expenditure. There may be a case for overall national investment by the Commonwealth, however, that is not relevant at the state/territory level when comparing expenditure levels.

We do not suggest that a mere increase in funding would address the problems highlighted by the professionals and reflected in the data. There clearly needs to be a focus on designing and targeting services in consultation with frontline professionals.

The charts published here unarguably and distressingly highlight the low priority which the ACT government has given to the issues we have raised.

Jon Stanhope is a former chief minister of the ACT and Dr Khalid Ahmed a former senior ACT Treasury official.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply