LAST December, a team of scientists got in a helicopter and dropped in on some inaccessible mountainous areas near Canberra to collect insects, and found hundreds that are likely to be new to science.

The field trip to Namadgi and Kosciuszko National Parks was our local area’s turn in an ongoing series of nationwide biodiversity surveys called Bush Blitz.

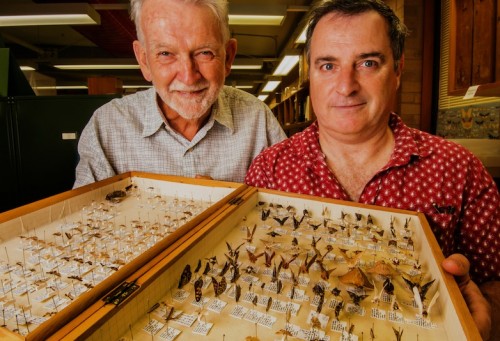

Among the team was Dr David Yeates, the director of the CSIRO’s Australian National Insect Collection, a vast room filled with row after row of metal cabinets holding specimens of Australian insects (and a few other creepy crawlies like spiders, scorpions, mites, worms and centipedes).

“Every day, some of us got in the helicopter and went off to some inaccessible parts of the Brindabellas; some of the really interesting parts up there are these hanging swamps right near the tops of all the mountains… because there’s a lot of free water, interesting plants and a lot of interesting insects and invertebrates in those places,” he says.

“They’re really quite interesting environments across the board – you know, corroboree frogs, broad-toothed rats and things live in them – and luckily they’re also high biodiversity spots for insects as well.”

They mostly used huge “malaise traps” to catch the insects, Yeates explains, which look something like a tent and feature “killing bottles” filled with ethyl alcohol.

“We bring back tubs and tubs of these tubes, all full of ‘bug soup’ in ethanol, and we have to painstakingly go through all those samples to pull out what’s interesting and new and relevant, and then we dry them out and pin them up and we can start to do the further identification and research on them,” he explains.

Glen Cocking, a moth-mad volunteer curator at the National Insect Collection, went out at night with gigantic lights to catch his quarry.

Photo by Gary Schafer

“I was trying to see if there’s anything like that in the collection and I’ve just about given up.”

Yeates says “we’re still very much in the age of discovery” for invertebrates, the spineless creatures that account for about 95 per cent of animals, and that’s why the National Insect Collection takes in more than 100,000 new specimens every year for scientists like Yeates to compare with what is already there. If they can’t find a match, in it goes.

“In fact, one of the best places to find new species of insects in Australia is in those cabinets,” he says.

“There’s lots of ones in there that haven’t been described yet. It can take years and often, students or researchers from overseas come here and spend time working on our collection. It’s certainly the case that all collections like this are full of invertebrates, insects particularly, that don’t yet have names.”

It’s estimated the number of different species of insect living in Australia is up around 200,000, and “we only have names for about 25 to 30 per cent, give or take,” says Yeates.

It’s the same everywhere. There’s likely tens of millions of insect species in the world, scientists reckon, made up of somewhere around a quintillion individual six-legged beasts. That’s 1 with 18 zeroes after it.

The work helps highlight Australia’s biodiversity to assist environmental management, and the specimens in the 86-year-old physical database will be useful to science for decades to come.

“It’s like a Catch-22,” says Yeates. “We’ve got this fabulous mega diversity out there but we don’t really have the resources [in Australia] to deal with it effectively in the appropriate timeframe. In fact, the scale of the issue for invertebrates is so big that no country probably has the resources to deal with it effectively.”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply