A state funeral for Bob Hawke, Australia’s 23rd prime minister, will be held at the Sydney Opera House on Friday, June 14. Here Canberra author CONSTANCE LARMOUR shares an insight into Hawke and an early mentor.

WHEN in 1967 I sought to interview Bob Hawke for my thesis on Judge Alfred Foster of the then Arbitration Court, he was quite tetchy.

Hawke, the ACTU’s research officer curtly offered me only a short, half-hour time slot on a specific date. I meekly agreed to travel from Geelong to the Melbourne ACTU office for that limited appointment.

I discovered that the reason for his apparent annoyance at my request was that he had himself always planned to write the story of “this fascinating man” – Judge Foster.

I discovered that the reason for his apparent annoyance at my request was that he had himself always planned to write the story of “this fascinating man” – Judge Foster.

However, as he said later in the preface that he wrote for my subsequent biography of Foster, events “not entirely beyond my control precluded that”.

Bob Hawke, as his former press secretary Barry Cassidy and others have noted, did not hold a grudge. In the event, he was generous with both his time and in lending me his brilliant but then unpublished Oxford University thesis on the role of the Australian Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration with special reference to the concept of a basic wage, which he had submitted in 1955.

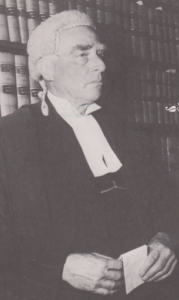

By the 1950s Judge Foster was already a legend in Labor politics and in Australian industrial arbitration. He had been responsible for the 40-hour week decision in 1947 (reducing the standard hours of work from 44) and also for the staggering one pound rise in the Basic Wage Case of 1950.

While these decisions had earned him the approval of workers generally, his jailing of Communist union leaders during the prolonged 1949 coal strikes had caused much angst.

Hawke was appointed the ACTU advocate for the 1959 Basic Wage Case, and appeared before Judge Foster, Full Court President Judge Kirby and Judge Gallagher.

Hawke said that at first Foster complained at the appointment of an “unknown” to such a responsible job as presenting the unions’ case to the (by then) Arbitration Commission.

When Hawke’s style and the extent of his preparation became apparent, Foster changed his opinion. Hawke was able to present a depth of economic analysis not seen in earlier cases. Foster asked many questions from the bench, giving Hawke the chance to explain more fully the economic implications of previously accepted and unquestioned assumptions.

A rapport developed between the new advocate and the senior judge to the extent, Hawke said, that it seemed as if there were two union advocates in court.

Subsequently, the judge and the advocate became firm friends. Hawke would visit Foster at his Sandringham home on Sunday mornings to sit and listen, over a few drinks, “to the thoughts and experience of a very great Australian”.

Hawke’s study of Foster may have enabled him to avoid some of the pitfalls in what could have been a remarkably similar career. In the preface to “Labor Judge“, Hawke, by then Prime Minister, said of Foster: “What I think intrigued me most about this extraordinarily gifted and complex man was the struggle he constantly waged within himself to stop frustration merging into bitterness.

“His frustrations were indeed of enormous dimensions. Three times an unsuccessful Labor candidate for Federal parliament, he believed the leadership of the party and the prime ministership would have been legitimately within his grasp.”

To say that he had been disillusioned and disappointed in his political ambitions would be quite an understatement.

Foster’s ambitions were again thwarted when, in 1956, Chief Judge Kelly died and Foster, as the senior judge, expected to be appointed as president of the Arbitration Commission. This position was awarded to Judge Kirby.

Although initially Foster’s junior, Kirby was considered to be a diplomat and conciliator, whereas Foster was often impatient, refused to compromise and had made important political enemies.

Hawke commented on the lasting effect this had on Foster, and perhaps on his judgments: “Once departed from the area of political opportunity, he felt deeply aggrieved that his distinguished career on the Arbitration Court was not rewarded with the presidency of the tribunal ahead of Richard Kirby towards whom he indeed came to feel great bitterness”.

Hawke’s close observation led him to conclude that Foster “would have liked to have done so much more, but it was important that the fight should go on for a better world.”

In his ascension to the leadership of the Labor Party and to the prime ministership, Hawke shared this commitment to improve social conditions.

In working to deliver policies and outcomes which he believed were right rather than politically expedient, Hawke seemingly avoided the angst that plagued his mentor.

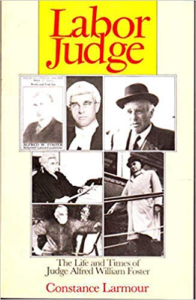

Constance Larmour is the author of “Labor Judge: The Life and Times of Judge Alfred William Foster” (Hale & Iremonger, 1985). Foster, who was born in 1886, died in November, 1962.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply