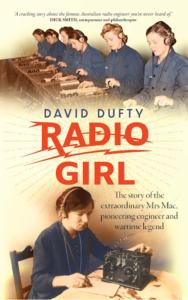

WHEN Canberra biographer David Dufty was told he should write a book about Violet McKenzie, he replied: “Who?”

And then he found out that Violet, known to “her girls” as Mrs Mac, was Australia’s first female engineer and was also the reason the Navy started enrolling women.

Becoming increasingly intrigued by this extraordinary woman and the part she played in the nation’s history, David decided he couldn’t resist writing “Radio Girl”, which is published on April 28.

“She was such a remarkable woman and had such an extraordinary life and I felt it would make a great story that people would enjoy and be fascinated by,” David says.

“It’s also an important Australian story, a story about an important but overlooked Australian woman.”

The inspiration first came to light when David was writing his award-winning biography, “The Secret Code-Breakers of Central Bureau”.

“In 2014 a retired spy suggested the idea to me as we had a cup of tea in her living room,” David says.

“I was there to interview her about Australia’s code-breaking activities during World War II.

“I found [Mrs Mac] tangentially throughout that story and the more I looked into her the more interesting she became.”

David even had a chapter on Mrs Mac in that book, not because she was a codebreaker, but because she trained a lot of female codebreakers during the war in signals and Morse code.

He says she was responsible for a lot of women becoming involved in codebreaking intelligence in Australia.

“She knew that Australia would run out of certain skills that she was an expert in. She didn’t get any funding and [spent all her fortune to] set up a Morse code and signalling school for women and teenage girls,” David says.

Called the “Woolshed”, and based in Sydney, David says she trained more than 150 women in signalling when World War II had started, and had several hundred in training.

At the time, the government was desperate for people who knew Morse code, but the air force wouldn’t take women, David says. So, she went to the navy.

“Someone came out to check out her Morse-code school and was blown away,” he says.

“That’s how women joined the navy in Australia. She changed Australia’s participation in the war.

“She was too old to enlist but she was the person that persuaded the Australian Navy to allow women to join.”

When some of Mrs Mac’s “girls” were able to join the navy, David says she escorted them to Harman, a Navy signals base between Canberra and Queanbeyan, where she stayed with them for a few days until they got settled.

“That’s where the first women in the Australian Navy were stationed,” he says.

He says she also went a step further by paying for, and delivering, a piano to their living quarters.

“She trained more than 2000 women by the end of the war but even that wasn’t enough,” David says.

“The Woolshed became the main signals training centre during World War ll and it trained more than 10,000 men. It was an incredible achievement.”

After the war David says she switched her focus on rehabilitating veterans, and she also trained almost all Qantas pilots in signals after the war.

“She just had this amazing reputation in all sorts of parts in Australian lives,” he says.

“Her biggest achievement was her signalling school in the Woolshed in Sydney and getting women into the navy.

“But they weren’t her only achievements. She did so much and I just kept discovering new stuff.”

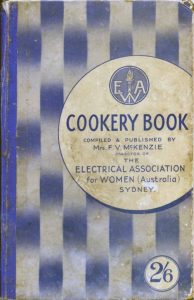

She founded the first electric store in Australia, before Dick Smith, and she also founded a successful publishing enterprise and wrote a best-selling cookbook. She set up an organisation called the Electrical Association for Women and she wanted to educate and empower women through electrical appliances.

At the time, David says electrical appliances were a new thing and her goal was to liberate women by teaching them how to use these appliances.

“She was keen to educate women in all the new ways to make their lives easier,” he says.

And, when she realised there were no cookbooks geared up for electricity, she wrote the “All Electrical Cookery Book”.

“It was the first of its kind,” David says.

“Radio Girl” will be David’s third book, and he says it was a lot easier to write than his last one on codebreakers, which was a topic where people had gone to a great deal of trouble to obscure and erase records.

“Violet McKenzie, herself, didn’t leave a memoir but luckily she was the subject of a lot of feature articles in the news because she featured so prominently in getting people trained, and was a key person, so she appeared in a lot of interviews,” he says.

“Violet McKenzie, herself, didn’t leave a memoir but luckily she was the subject of a lot of feature articles in the news because she featured so prominently in getting people trained, and was a key person, so she appeared in a lot of interviews,” he says.

David even put a note in the “Sydney Morning Herald” calling for people to ring him if they had known her and got a lot of responses.

“I had calls from retired pilots or women who had been in the WRANS,” he says.

“Everyone that rang loved her and were excited about me writing her story.

“She never had any children, except for one daughter who died at birth, and even though she didn’t have any children of her own, all of the women she trained she continued to mentor them after the war.

“In a way, she sort of had many children.”

“Radio Girl” (Allen & Unwin, $29.99)

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply