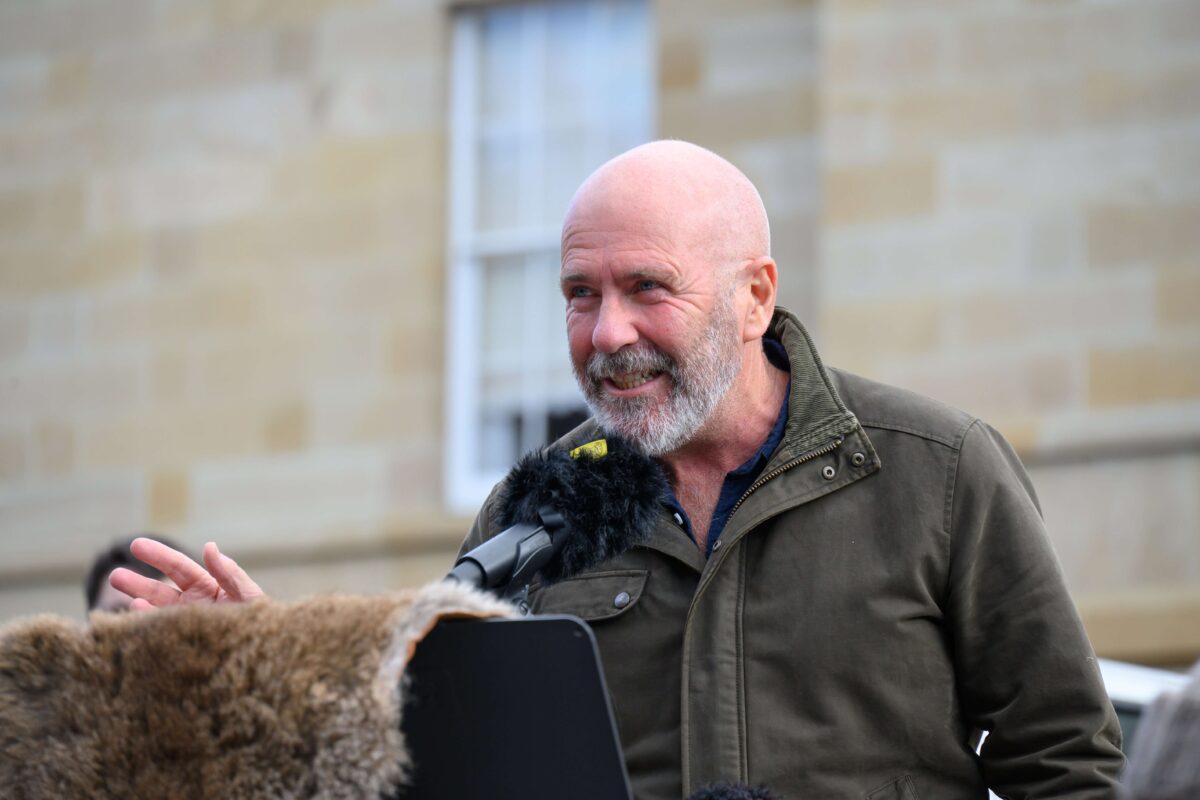

WHEN Iain Sinclair was honoured at Melbourne’s recent Green Room Awards for his direction of the Melbourne Theatre Company’s “A View from the Bridge”, there was no shortage of old mates in Canberra to say, “I told you he’d do well.”

In fact, the former Canberra director has been doing well for some years, with a swag of awards, including the 2017 Stuart Wagstaff Memorial Award for Best Director in Sydney and a Sydney Theatre Critics Award for directing “Of Mice and Men”, the most recent of his shows to be seen here.

Sinclair’s reputation for teaching actors how to respect a text has been recently described by actor Anthony Gooley as “exacting and ferocious”, and even when dealing with Australian accents he once told his cast “If we ‘Summer Bay’ this thing, we kill it”.

His “day job” is at Melbourne’s 16th Street Actors’ Studio, but he was previously senior dramaturg at Playwriting Australia in Sydney before he made the move to Melbourne, where the opportunities for directing were stronger.

We caught up last week as he and his partner, actor Meredith Penman, were busy juggling life as the parents of two toddlers, Robin and Stella, while he was teaching a six-week Zoom course on acting.

Somewhat smarting from the MTC’s cancellation of his planned production of Joanna Murray-Smith’s play “Berlin”, which would have opened on April 25, he says winning the Green Room Award was just the cream on the top of a favourite job – directing plays by Arthur Miller.

Sinclair makes no bones about this partiality, saying, “when it comes to the truly great writers of tragedy, you can count them on the fingers of one hand: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Shakespeare and Arthur Miller”.

To him, Miller was the premier modern exponent of tragedy, “dealing with small human frailties in a world of pitiless gods… He’s more in the line of Euripides, writing about real people,” he says.

“All of Miller’s works are informed by ancient Greek theatre – and remember that like Elizabethan theatre, that had no lighting or sound effects.”

In a recent comment, Cate Blanchett, to whom he had been assistant director when she was at Sydney Theatre Company, said he’d worked there in his “early career”, but that is far from true.

Sinclair’s connections with Canberra are deep and his mum still lives here in Watson.

His rise to the top was by no means meteoric, but as he says, “The number one skill in theatre is tenacity”, and without doubt he cut his theatrical teeth in the ACT.

Not born in Canberra but rather Uganda, he came to the ANU in the 1990s with the intention of studying Chinese and politics, but was quickly lured into theatre studies with Geoffrey Borny. He also appeared in young male lead roles for Canberra REP and in The Looking Glass Theatre’s Shakespeare nights on Aspen Island.

A grittier, gutsier Sinclair was to surface when, after putting himself through the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where he took out an MA in text and performance studies, he came home to form the innovative Elbow Theatre, staging local scripts like Mary Rachel Brown’s “A Streetcar Named Datsun 120Y” and verbally demanding texts by American playwrights like David Rabe and Wallace Shawn, often with local balladeer Fred Smith introducing the evenings in song.

Elbow Theatre battled on for six years, receiving four Canberra Critics Circle Awards. But despite fundraising efforts – at the end of one such they blew the profits on treating the audience to a curry supper – it proved impossible to sustain.

“Money was never my strong suit,” Sinclair admits.

He eventually made the break with Canberra, moved to Sydney and started doing productions for small companies like Tamarama Rock Surfers in Woolloomooloo and The Stables Theatre in Kings Cross.

I saw some of those early productions, including his “Lord of the Flies”, where he transformed The Stables into a desert island using lots of sand and a restaging of Rabe’s “Hurlyburly” with Alex Dimitriades and Ed Wightman in lead roles.

While he won awards, notably for directing Kate Mulvany’s “The Seed” at Company B Belvoir in 2008, Sinclair’s big break came when he joined the STC as assistant director, working with Blanchett, Jean-Pierre Mignon, Gale Edwards and Max Stafford-Clark, who would later invite him to tour the UK as a member of his own company.

“Working with Max was the real game-changer for me,” Sinclair says.

“He showed me his technique… but my big break was doing ‘Our Town’ at Sydney Opera House in 2010.”

Then Blanchett invited him to direct Lorca’s “Blood Wedding” at the Wharf Theatre in 2011 for which, armed with Spanish picked up during visits to his father in Chile, he translated the whole text.

There’s been a lot of water under the bridge since then, and Sinclair has become one of the most eminent directors in the country, so let’s give him the last word.

“I think my job is putting the actor in the play right back on the floor. For too long it’s been about the actor and director,” he tells us.

“I’ve always been interested in storytelling so I like to work out how to empower and how to understand the story.

“Actors do the work but my job is the mediator, like the best man at the wedding.”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply