A NGAMBRI descendent of Henry “Black Harry” Williams is calling out the ACT government, accusing it of “cultural genocide” after Canberra’s first people, the Ngambri people, have been excluded from its own history.

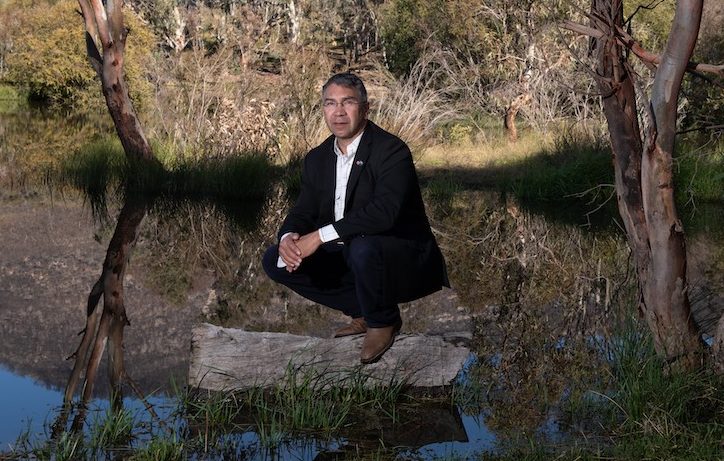

“Our family [has] produced our genealogy, an evidence of our connection to country since the arrival of Europeans into the Kambri or the Ngambri region,” says Paul House, who has watched his children grow up with “Welcome to Ngunnawal” signs, while the Ngambri people continue to be written out of the ACT’s history.

“I’ve got twin daughters that are nearly 18, and they go to school here and all they see is welcome to Ngunnawal. They’re actually Ngambri people, they’re born here, our ancestors were born here.

“We’ve proved connection right across the Canberra landscape and the ACT government totally ignores it.”

Paul says the ACT government recognises members of the Ngunnawal nation as descendants of the original inhabitants of this region, but there is no specific recognition of the Ngambri group outside of this broader acknowledgement.

The ACT Greens has gone a step further and, after leading a successful motion in the ACT Legislative Assembly, the Ngunnawal language will be used at the start of every sitting day from October.

Inconsistently, the federal government, in the House of Representatives, acknowledges the Ngambri and the Ngunnawal people as traditional custodians of the Canberra area, and so does the ANU. So, why doesn’t the ACT government?

“This current government is stealing the identity away from Ngambri people on country. They’re stealing it, they’re trying to reinterpret, they’re trying to whitewash the true history of this country here in the ACT,” says Paul, whose mother, indigenous elder and 2006 Canberra Citizen of the Year, Dr Matilda House, has been pushing for the Ngambri people to be recognised for decades.

“We’re even excluded from doing welcome to country on our own country,” Paul says.

In 2001, a detailed summary of the historical evidence relating to the Ngambri people, written by Ann Jackson-Nakano, was published by ANU Press called “The Kamberri: a history from the records of Aboriginal families in the Canberra-Queanbeyan district and surrounds 1820-1927 and historical overview 1928-2001”.

The same year, Paul’s uncle Nurrie Arnold Williams, on behalf of the Ngambri descendants, signed an agreement for a “99 Year Namadgi Special Aboriginal Lease”, which saw them give up a lodged native title claim in the Federal Court to have a say, in partnership with the government, in the management of Namadgi National Park. Almost 20 years later and they are still waiting on this agreement to be honoured.

“Our Ngambri ancestors were the custodians of the country south-west of Weereewa (Lake George), which includes the modern ACT. The name of the capital, Canberra, is derived from that of our ancestral group, the Ngambri,” Paul says.

“What concerns many Ngambri the most is the lack of formal recognition by ACT governments and the broader ACT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community of the special place of Ngambri descendants in this region.

“Today, the Ngambri as a group do not own or control any land. We’ve only been given token recognition as having historical connections to Namadgi, and our relatives from neighbouring groups piggy-backed on those connections and now dominate discussions.”

So, how did the government get things so wrong? Well, according to Paul, it goes back to when Ngambri (Kamberri), Walgalu speaking “Black Harry” married a Wallabalooa, Ngunnawal-speaking woman from Yass, Ellen Grosvenor.

“It is because of his marriage to Ellen that Black Harry’s descendants could identify as Ngunnawal-speaking Wallabalooa as well as Ngambri,” he says.

Things became more complicated following the passing of the “Native Title Act” in 1994, and more specifically, according to Paul, beginning with Kate Carnell’s government, who allegedly forced false alignments between a few indigenous family groups.

“For our native title claim to Namadgi National Park, Ngambri descendants were told that the so-called ‘three claimant groups’ had to ‘merge as one, otherwise you’ll get nothing’,” he says.

“The only way the other two claimant groups could be involved in native title claims was by piggy-backing on Ngambri genealogies. Some of these so-called claimants are related to us through our great, great grandmother Ellen’s line and also through the line of our grandmother, Pearly Williams, but this does not give them rights to Ngambri country.

“Some of them are related to Ngambri descendants through inter-marriage but our own lore and custom do not recognise them as bona fide Ngambri, with rights to Ngambri country.”

Paul accepts that this is a complicated issue for the ACT government, but believes, since they had a role in creating the issue, that they should have a role in fixing it.

“It is more convenient for the government to throw all of us under the linguistic name ‘Ngunnawal’ so we’ll be easier to ‘govern’,” Paul says.

“We realise governments are in a hurry to demonstrate their support of Aboriginal peoples in modern times, but their endorsement of false claimants serves their own purposes, not ours.”

The Ngambri people refuse to go away, according to Paul, who says they will continue to speak up until they get formal recognition.

“We are prepared to negotiate with the ACT government and with our relatives from non-Ngambri descent lines, but on our terms,” he says.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply