A NEW memorial featuring burial poles at ANU marks an important step in making sure indigenous Australians have a say about how their genetics are used by science.

The instalment of burial poles, revealed during National Reconciliation Week, represents the return of indigenous blood samples, something that Azure Hermes has been working on for the past two years in her role at ANU.

Many of the samples have been sitting at ANU for 50 years, and Ms Hermes, the deputy director of the ANU National Centre for Indigenous Genomics (NCIG), is making sure they get back to where they came from.

“My family is in this collection. These samples are like my own flesh and blood,” Ms Hermes says.

“I see the 7000 people in our collection as if they’re my own family. I want to make sure that the advice I give would be the same advice I would give my own flesh and blood.

“I want to make sure that their voice is heard and represents what they want.”

So far, Ms Hermes has worked with thousands of people from four indigenous communities to gather consent on how the samples are used and where they belong.

“It is a lot of work, and it takes a lot of time and money, but it’s so important these samples are not just stored in a freezer and forgotten about,” she says.

“The high level of consultation that NCIG provides is a first of its kind. We hope that in the years to come, it becomes the standard practice for all researchers working with indigenous communities.”

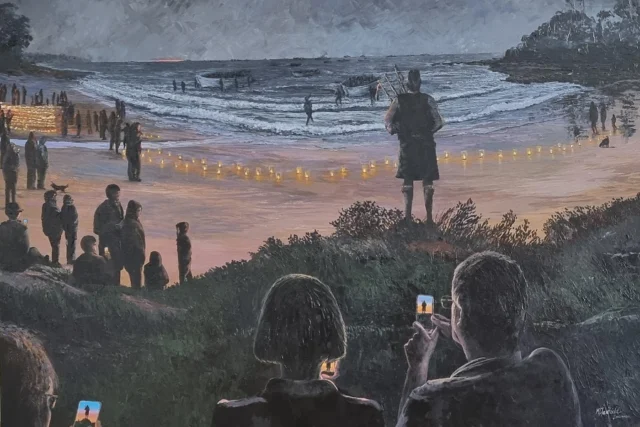

The instalment will see new burial poles representing the return of the blood samples from the Galiwin’ku community on Elcho Island unveiled at the ANU campus in Canberra.

The ceremony at ANU follows the repatriation of blood samples to the people of Galiwin’ku in 2019 – their final step on a long and difficult journey home.

Ms Hermes says the formal memorial site represents a powerful step forward in reconciling a challenging chapter from Australia’s past.

The memorial and burial poles highlight new conduct for human genomic research.

“We commissioned burial poles from the island because we wanted to celebrate this reconciliation process,” Ms Hermes says.

The burial poles belong to the two moiety groups of the Galiwin’ku community – Yirritja and Dhuwa – and represent people who have passed away.

The poles at ANU mirror burial poles on Galiwin’ku country, made in the traditional style, decorated by an artist from each of the two groups.

More than 200 biological samples from the Galiwin’ku community of Elcho Island in East Arnhem Land have been returned to their home.

The samples were first collected after a typhoid outbreak on Elcho Island in 1968 and 1969 but Ms Hermes says it is unclear if consent was given to keep the samples for medical research.

Working closely with the people of Galiwin’ku, Ms Hermes was able to negotiate a future for the samples, and lead the process of repatriation for the samples of those who had passed away.

“Those samples had been living at the university for 50 years and to these communities it means so much more than three millimetres of blood,” she says.

“It could mean their loved one hasn’t been able to move on to the next world, and that it might be the reason for their bad luck. These samples have a real human connection.”

Ms Hermes says it has been “difficult to reconcile” the history of the 7000 samples in the ANU collection and the important research and discoveries they unlock. This includes debilitating and life-threatening genetic diseases.

“What gives me hope is that we are changing the conversation around genomic research, and giving decision-making power back to the participants, Aboriginal people can now have a say in what happens to their sample and their data. They hold that power now,” she says.

“This is the first time that we’ve repatriated samples. With this ceremony, we are cementing our relationship with Galiwin’ku.”

After 11 months of negotiation, the community also gave permission for about 400 Galiwin’ku blood samples from those who are still alive to be sequenced and then disposed of in Canberra.

Before being disposed of, the DNA information from the samples will be added to NCIG’s genome biobank, helping future scientific discoveries.

The biobank has some 6000 samples for which consent is yet to be given and Ms Hermes is working with other communities, including in the Kimberley, to help them find a home.

“My role is to find these 7,000 people or their families and talk about consent,” she says.

“Some communities have been in complete shock. They have to think about what it means to have these blood samples sitting in Canberra.”

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply