“It is true that we are blessed by not even having to consider the need to bribe a judge; however, there are factors other than money that can, and do, damage the quality of our legal processes,” writes legal columnist HUGH SELBY.

A YEAR ago, before the last federal election, more than half of us no longer had faith in government or in the media.

We expected to be lied to both by those who had been elected and those who claim to hold the powerful to account.

But what do we think of our judges/tribunal members (judges)? Do we trust them?

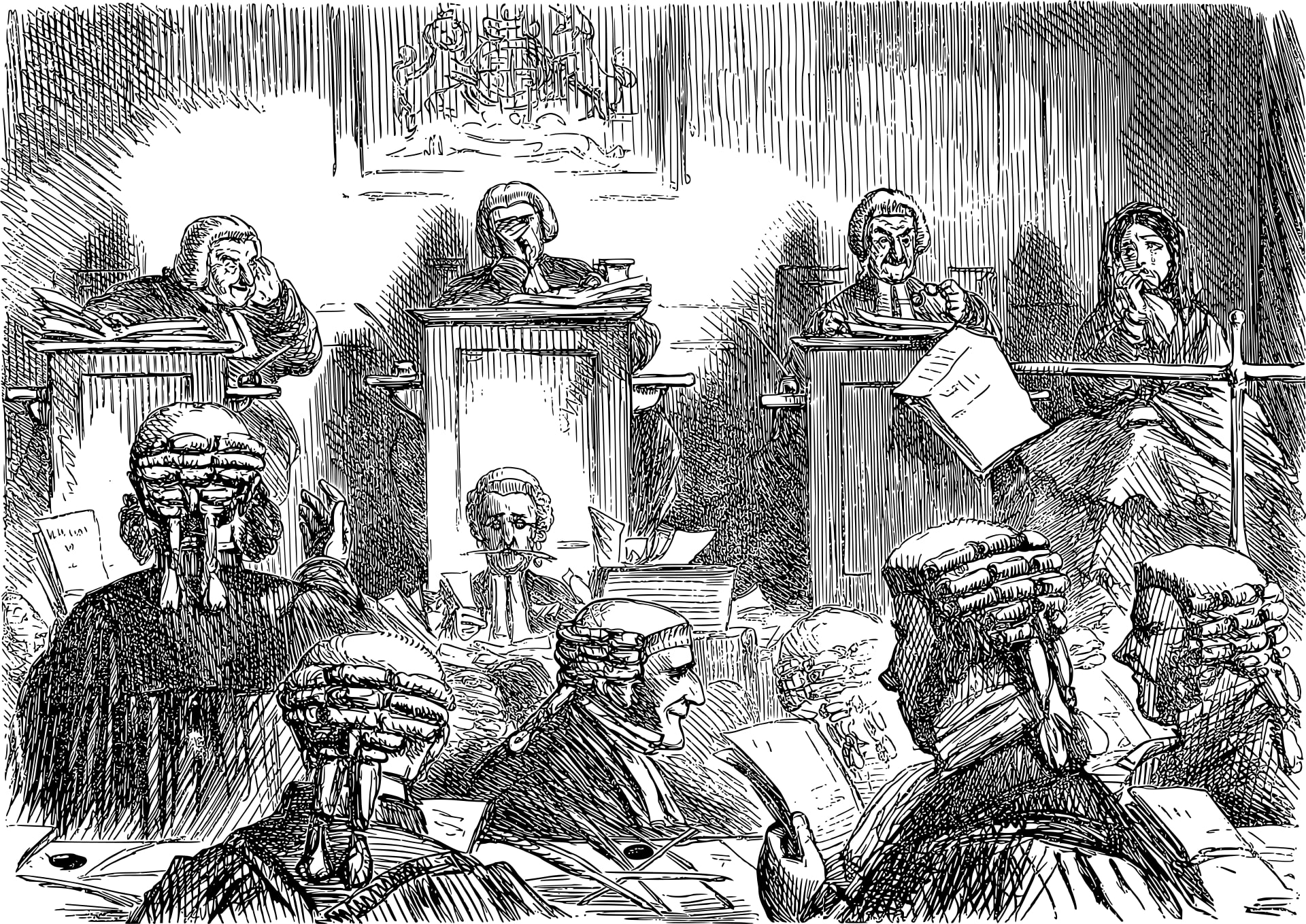

Their job is to filter and prioritise the facts put before them by the competing parties, and then to impose upon those facts an outcome of winners and losers that is derived from legal rules.

Those rules are just another kind of policy, the judges just another group of the powerful.

Aberrations, such as the Morrison government’s highly paid jobs on the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, seemingly for their mates, are being put right by the Albanese government.

That said, it seems likely that the present levels of respect for our legal system reflect “out of sight and mind” as much as any informed opinion.

It is true that we are blessed by not even having to consider the need to bribe a judge; however, there are factors other than money that can, and do, damage the quality of our legal processes.

The point of this article is to alert you to one such factor and a possible solution.

The focus is upon one form of “conflict of interest”, a situation where someone who is offering advice or making a decision has divided, incompatible “interests”.

Typically, a personal interest competes with another required interest. An example is the professional sports player who lays bets on a game in which she/he is playing. Another example is the politician who makes planning decisions for the benefit of their friends or themselves instead of for the community.

When a judge may determine a case for reasons other than following the law, that too shows a conflict of interest. Examples include:

- A civil case in which the judge has shares in one of the corporate parties;

- A criminal case in which the judge played weekly rounds of golf with the accused before the allegations of insider trading surfaced;

- A judge “bending” their decisions to ensure re-appointment;

- Allowing any of social or political connections, racism, sexism, to influence the outcome;

- A significant relationship between the judge and the lawyer/s for one party in the case, such as a long employment and mentor history.

- Judges and lawyers should reveal any prior relevant associations in open court, so that there can be open discussion among all parties as to whether the judge continues or “recuses” themself.

A failure to disclose and a later discovery by one party of that “association” or prejudiced thought pattern leads to a recusal application. It may be necessary for another judge to rehear the case.

A key aspect of the legal test to stay or go is to ask whether the reasonable lay observer (ie, not lawyer, not judge) would have an “apprehension of bias” by the judge.

This requires judges to presume to know what such reasonable lay observers would think. This is impossible. They have developed their careers by avoiding the reasonable lay observer who we know as the person we see on the bus or tram, the weekend ref in the kids’ teams sports, or the non-lawyers at the community barbecue fundraiser.

Do I jest? Alas, no. “Recusal” is the right thing to do to ensure the continued respect for the office of judge by the lay users of the legal system.

The priority is the respect for the office, not the incumbent. But judges who have failed to declare an interest that the pub test marks as “sus” will resort to an inapplicable self-defence that uses the subjective approach of, “look at who I am and what I do – how could I be seen as possibly prejudiced?”

Therefore, if the issue arises of whether a judge should hear a case then that issue – as with any complaint about judge conduct – should be decided by an “external” lay body: so not the judge and not their “mates”.

We need a Judicial Commission because:

- Judges are as fallible as the rest of us – especially when it comes to “self-interest” – be that advancing their own interests or defending themselves;

- Collegiality and/or dislikes among judges in their daily working environment are inevitable;

- Judges need to be accountable to their community; and,

- To avoid recusal evaluations being self-justifying, three independent lay people should decide the issue by a majority: stay or go.

Will this policy idea get up in our town or succumb to “same old, same old”?

Hugh Selby is our legal affairs commentator. His free podcasts on “Witness Essentials” and “Advocacy in court: preparation and performance” can be heard on the best known podcast sites.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply