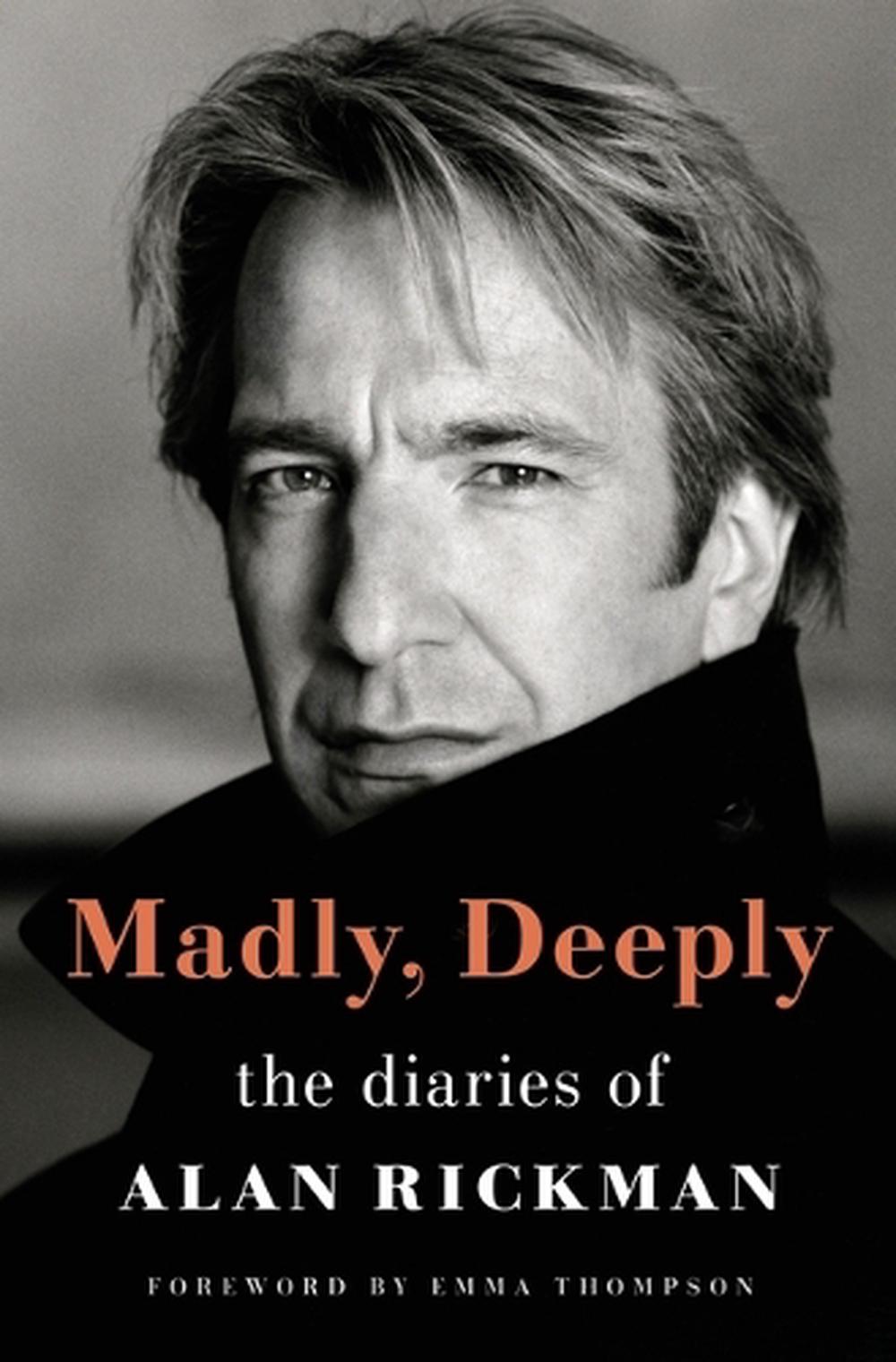

COLIN STEELE reviews two books based on famous faces – Alan Rickman’s diaries and a biography of Noel Coward.

SIMONE de Beauvoir once wrote “what an odd thing a diary is: the things you omitted are more important than those you put in”.

This occasionally appears to be the case in “Madly, Deeply: the diaries of Alan Rickman”.

Editor Alan Taylor, in his introduction, writes: “Why Rickman kept a diary is unclear”. However, many readers will be grateful that we have them, covering the years from 1993 until just before Rickman’s death in January 2016.

Alan Rickman is best remembered for his roles as Hans Gruber in “Die Hard”; the Sheriff of Nottingham in “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves”; Harry in “Love Actually” and Severus Snape in the “Harry Potter” series. He clearly developed a disdain for interviewers who constantly asked about these films, comparing them to “tired dogs with a very old slipper”.

Rickman’s diary entries are often short, at times being almost bullet points. He lists having a May 2002 meeting with Daniel Day-Lewis but does not recount any detail from it. There are many lunches and dinners, which has led one reviewer to suggest that the book should be retitled “Dine Hard”.

Nonetheless, there are many interesting and humorous entries, particularly those revealing the foibles and inner workings of the movie industry. Rickman wrote in 1994: “To work or to hang around for five hours is the question”.

Rickman was a lifelong member of the Labour Party. He undoubtedly took pleasure in July 2001 at Wimbledon when he met former British Prime Minister John Major. Major said: “You have given us so much enjoyment”, to which Rickman replied: “I wish I could say the same of you”.

Rickman had a 46-year relationship with academic and Labour politician Rima Horton, whom he married in 2012. Although he does confess to Emma Thompson, “there but for the grace…” when he learns of Hugh Grant’s arrest with a sex worker in Hollywood. Rima was with him at the end when he was dying with pancreatic cancer and the diary becomes full of hospital appointments and re-watching his favourite TV programs.

Rickman as an actor has been termed “sardonic, aloof, witty and withering, yet with undercurrents of warmth that could surface when needed”. The Rickman diaries definitely reaffirm that image.

“THE New York Times” wrote in 2002 of Rickman, when he appeared in a revival of Coward’s “Private Lives”: “No man, at least not since Noël Coward, wore a dressing gown with more slippery ease or dangerous intent.”

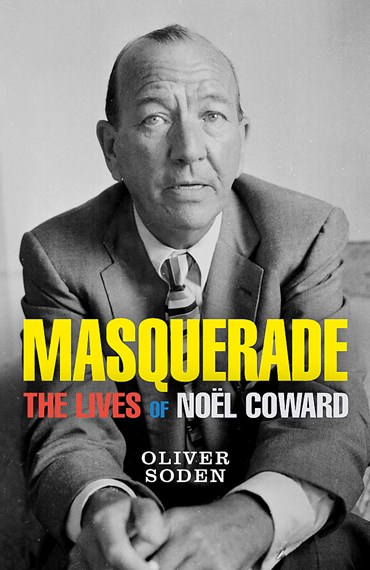

The indisputable image of Noel Coward (1899-1973), writer, actor, singer, songwriter and occasional World War II spy, is of a figure in an elegant dressing gown, with a cigarette holder, effortlessly delivering a stream of witticisms.

Noel Coward’s diaries, reissued in 2022 with a new introduction by Stephen Fry, never fully revealed the inner Noel Coward. The latest, and undoubtedly best biographer of Coward, Oliver Soden, deliberately titles his book “Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward” and comes closest to removing Coward’s public masks.

There are constant revivals of Coward’s most famous plays “Private Lives”, “Hay Fever” and “Blithe Spirit”, while songs such as “Mad About The Boy”, “Someday I’ll Find You” and “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” are instantly recognisable. Frank Sinatra once said: “If you want to hear how songs should be sung, listen to Mr Coward.”

Overall, Noel Coward wrote some 50 plays, nine musicals, 675 songs as well as novels, short stories and screenplays. His last film performance was in the 1969 film “The Italian Job” in which he played the gangster Mr Bridger. Coward’s 1940s films “In Which We Serve” and “Brief Encounter” are classics to this day.

Soden, with extensive use of new archival material including unexpurgated diary material, breaks up his biographical analysis of Coward into nine segments of Coward’s life, each of which begins with a vignette in imitation of Coward’s style.

Coward was eminently suited to the 1920s, a decade which Soden describes as “cat’s cradles of laissez-faire sexuality and carefree infidelity”.

His 1924 play “The Vortex” rocked London society with its study of a decadent hostess with a young lover and a drug-addicted son. The rampant drug use that nearly had the play banned, now feels the most dated element of its still vibrant structure. By 1925 Coward had become the highest-paid writer in the world.

Soden superbly documents Coward’s personal “zig-zag” throughout the “alternately permissive and intolerant” decades of the 20th century when homosexuality was a criminal offence, in a sympathetic and revealing biography.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply