“There is no doubt that some ACT households on the national average income ($121,000) are living in poverty,” write JON STANHOPE and KHALID AHMED, who wonder, despite repeated urging from the Liberal opposition, why the ACT government refuses to look into poverty.

“NO child will live in poverty” is often used in scorn – as a put down – to refer to a goal or a commitment that is thought to be unrealistic or unachievable or too idealistic.

The statement, made by then prime minister Bob Hawke 35 years ago, included an ambitious timeframe of just three years, which could never be met because of how we define poverty and how we measure it.

The commonly used definition is based on a count of people/households who are below a “poverty line”, which is assumed as half (50 per cent) of the median income – the so-called Henderson Poverty Line.

Therefore if, say, the median household income is $2400 a week, a household with weekly income below $1200 would be classified as living in poverty. By definition then, there will always be households, and children, living in poverty and its eradication is simply impossible.

In light of this, the Melbourne Institute (Applied Economics and Social Research) publishes poverty line figures for households in 20 different circumstances including, for example, single people, couples and single parents or where the head of the income unit is employed or not.

For the March 2021 quarter, the poverty line estimates – and the institute stresses these are just estimates – vary (after tax) from $471.20 ($281.17 excluding housing costs) for a single person to $1405.63 ($1119.77 excluding housing costs) for a couple with four children. Accordingly:

- some households on annual income in the order of $90,000 will be deemed to be in poverty depending on their family circumstances;

- the community standard on what is a reasonable level of consumption (need) appears low with a single person expected to survive on just $40 a day, that is, if they can find accommodation for $190 a week; and

- housing costs would be a significant determinant of whether a household is in poverty.

It should also be noted that the estimates published by the Melbourne Institute relate to the national median income, adjusted for household characteristics. Cost of living varies across Australia, and the poverty line needs to be adjusted for a high-income, high-cost jurisdiction such as the ACT.

The incidence of poverty is clearly not readily measurable from the income or household composition data published by the ABS.

In general, poverty is masked and nowhere more so than in the ACT, where there is no particular “struggle street” and poverty is effectively hidden.

The University of NSW, in collaboration with ACOSS, also publishes a “Poverty in Australia” series. Its latest snapshot report provides the incidence rate of poverty as well as its depth (ie, the extent to which households are below the poverty line), and its trends.

Among the key findings of the report are that in 2019-20, 13.4 per cent of the people in Australia lived below the poverty line, which amounts to 3,319,000 people. One in six, or 761,000 Australian children (16.6 per cent) live in poverty. The average poverty gap was in excess of $300 a week.

In Australia, because of our social-security net and income-support system, one would expect that the abovementioned studies relate to relative poverty, rather than absolute poverty.

However, the case studies in the UNSW/ACOSS report reflect severe material deficit rather than just relative disadvantage, for example, working homeless or single mothers living in public housing being able to afford only a single meal a day.

Compounding the problem is the fact that poverty has been completely removed from the public sector lexicon – its study and discussion has been left to academics.

Our search of the most recent ACT budget papers showed not a single mention of the word “poverty”. We found two mentions of “income inequality” in a single paragraph claiming that it has decreased, and hence is apparently not a matter of concern to the ACT governmnet.

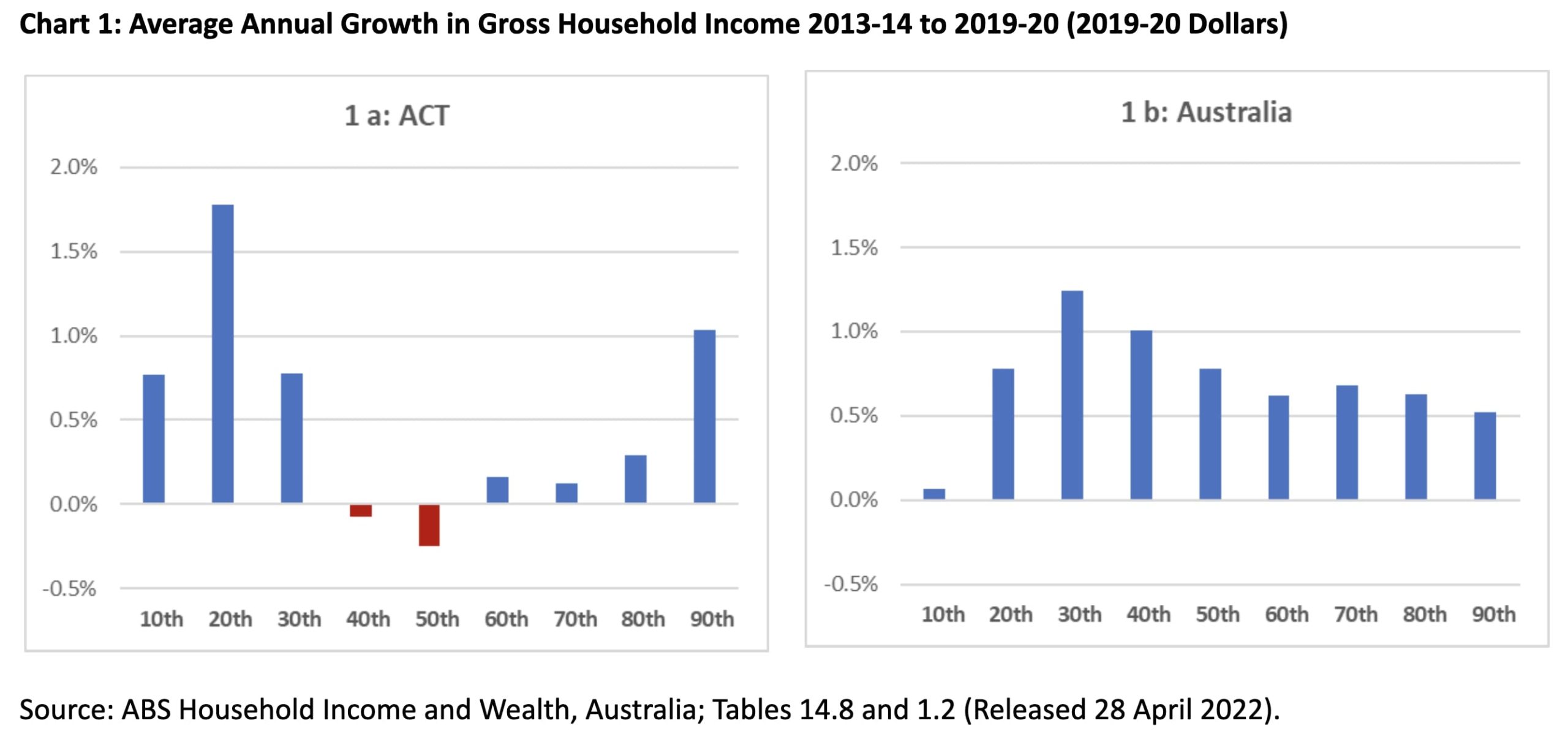

However, the ABS data on household income and its distribution provides a different picture. Here we acknowledge that the government may have been misled by a statistical limitation of the measure it utilises. Chart 1a shows the average annual growth in household incomes for each decile (10 per cent) in the ACT over the period 2013-14 to 2019-20. Chart 1b provides income growth at the national level.

The charts highlight a problem of the depleting middle in the ACT where incomes at the 40th and 50th percentile decreased at an average rate of 0.1 per cent and 0.2 per cent a year respectively over the six-year period. No such problem is evident at the national level where gross household incomes increased across all deciles.

Poverty is confronting in its manifestations and its implications, but it is generally hidden in the seemingly homogenous Canberra and the apparent affluence reflected in high-level statistics.

It would be wrong to think or suggest that poverty does not exist in the ACT. In fact, as noted above, the national poverty lines would need to be adjusted upwards for the ACT due to its relatively high median income. There is no doubt that some ACT households on the national average income ($121,000) are living in poverty.

It is not clear to us why the ACT government did not deign to mention the word “poverty” in its major annual policy document, the budget, or why it has opposed repeated attempts by the Liberal opposition to establish an inquiry into poverty.

Chief Minister Andrew Barr is on record insisting that poverty is a consequence of inadequate social security payments and hence a Commonwealth Government responsibility (over to you, Katy).

This is beyond the usual blame shifting and suggests an egregious lack of understanding of the causes of poverty. Social security support is, of course vital, but there is much that state and territory governments do that drives people into poverty.

In summary, that some people have more than others, and some have relatively less, is not a moral problem in itself – that some people do not have enough to get by is a moral challenge that we worry the people of Canberra do not take seriously.

Jon Stanhope is a former chief minister of the ACT and Dr Khalid Ahmed a former senior ACT Treasury official.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply