ANNA CREER reviews two new historical fiction books, one about an extraordinary love affair that engrossed a British prime minister at a time of war, the other of what awaits a victorious warrior king returning home from the Trojan War.

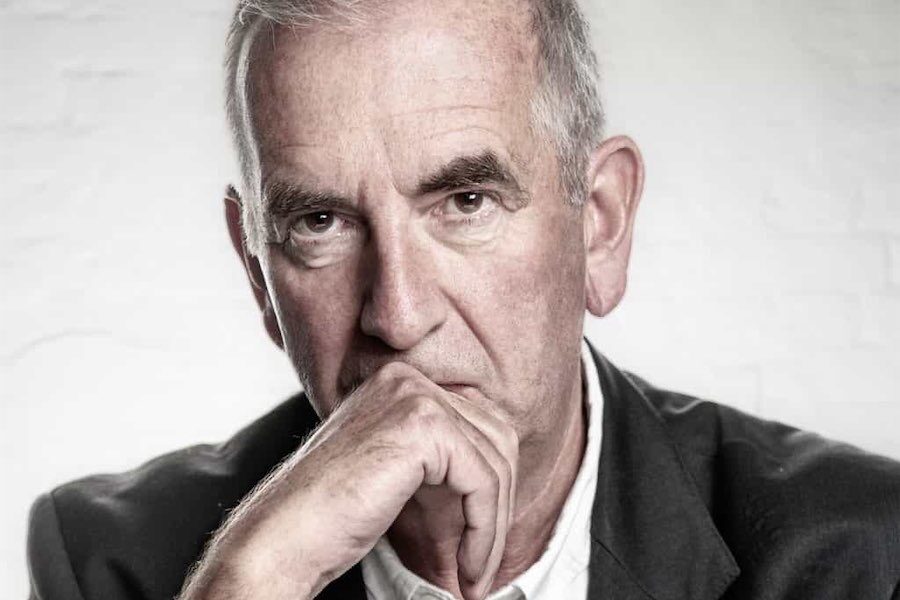

Robert Harris’ best-selling novels have notably explored power and those who wield it, from ancient Rome to the Vatican and World War II.

In his latest novel, Precipice, Harris retells the story of the tense events that led to Britain going to war in 1914 and the disastrous decision to expand the war to the Dardanelles in 1915.

At the same time, he reveals details of the extraordinary love affair between Britain’s Prime Minister, Asquith, aged 62 and the Hon Venetia Stanley, daughter of Baron Sheffield, aged 27.

Venetia is a bored socialite. She belongs to a group called “the Coterie” who gather at the Cafe Royal, music halls or, most often, the Cave of the Golden Café, a basement nightclub near Regent Street.

But every Friday, Venetia goes for a drive with Asquith, into the country for an hour and a half, in his chauffeur-driven limousine. The rear of the car is as big as an old fashioned carriage, with a curtained thick glass screen separating the passengers from the driver.

They meet regularly at lunches, dinners and country weekends but the car is the only place they can be alone together. She calls him “Prime”, he calls her “my darling”.

Venetia questions whether she loves Asquith, but she knows she likes him “for his kindness, his cleverness, his fame and power” and she enjoys “the thrill of it – the secrecy, the illicitness, the risk”.

Asquith is obsessed with Venetia, writing letters two or three times a day, insisting on replies (there were 12 postal deliveries a day in London in 1914).

Asquith wrote 560 letters to Venetia, often sharing sensitive information about government decisions. During their drives into the country he brings official papers to show her, carelessly throwing them out of the window. Inevitably, the secret service learns that information is being leaked and launches an investigation.

In Precipice, Harris opens a window on a world rushing to war, while Britain’s prime minister is constantly distracted by thoughts of his love for Venetia, writing letters to her even during important meetings of the War Cabinet.

Harris even suggests that Venetia’s ending of their affair influenced Asquith’s decision to agree to a coalition government on May 17 1915. It’s an astonishing story.

The Voyage Home is the third novel in Booker Prize-winning Pat Barker’s trilogy about the Trojan War, which began with The Silence of the Girls in 2018, followed by The Trojan Women in 2022.

Barker’s aim in writing her trilogy is to give a powerful voice to the women who are silent in Homer’s The Illiad and yet suffered rape and slavery, after their husbands and sons were murdered by the Greek army.

The Voyage Home reimagines the story of Agamemnon returning in triumph to Mycenae and Barker turns to Ritsa, an enslaved woman of Lyrnessus, who in the previous novels worked as a healer in the Greek hospital on the beach, to tell the story.

The Greeks are finally going home and the women of Troy are loaded on to ships: “Women of childbearing age shared out among the conquerors, some already pregnant with their children. What we were witnessing on that beach was the deliberate destruction of a people”.

Ritsa travels as a maid to Cassandra, daughter of Priam and now Agamemnon’s concubine.

Cassandra had been the high priestess of Apollo in Troy, able to foresee the future but cursed never to be believed. She’s considered “mad as a box of snakes” and she has already had a vision of Agamemnon’s death, like “a stuck pig on a slaughterhouse floor”, because “what he did in Troy was so horrific, so devoid of humanity, that even the gods were sickened”. She also knows she will die with him.

In Mycenae, Clytemnestra waits for her husband to return. She too hates Agamemnon because he sacrificed her beloved daughter Iphegenia to the gods at Aulis, in exchange for the wind to sail to Troy. She was there to witness her daughter pleading with her father to spare her.

Although Agamemnon is “a great king – arguably at the moment, the most powerful man in the world”, as he sets foot on Greek soil for the first time in 10 years, the two women, his wife and his concubine, have decided his fate.

The Voyage Home is compelling but bleak reading. Barker succeeds in reimagining the torment of women whose lives have been changed for-ever by the Trojan War. It is impressive.

Who can be trusted?

In a world of spin and confusion, there’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism in Canberra.

If you trust our work online and want to enforce the power of independent voices, I invite you to make a small contribution.

Every dollar of support is invested back into our journalism to help keep citynews.com.au strong and free.

Thank you,

Ian Meikle, editor

Leave a Reply